In 1992, Margaret Busby, Britain’s first black female publisher, edited an anthology of female African writers and female writers of African descent. Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Words and Writings by Women of African Descent from the Ancient Egyptian to the Present, published by Ballantine Books, was groundbreaking in its presentation and exposure of the work of female African writers.

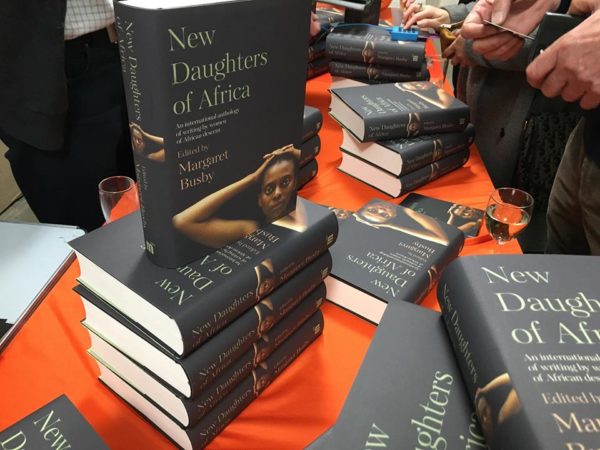

Twenty-seven years later, a sequel has arrived, published by HarperCollins. Also edited by Busby, New Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of 20th- and 21st-Century Writing by Women of African Descent “charts a contemporary literary canon from 1900 and captures their [female writers of African descent’s] continuing literary contribution as never before,” featuring 200 contributors including Aminatta Forna, Bernadine Evaristo, Sarah Ladipo Manyika, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Imbolo Mbue, Warsan Shire, Zadie Smith, Sefi Atta, Sisonke Msimang, Ayesha Harruna Attah, Diana Evans, Danielle Legros Georges, Bonnie Greer, Andrea Levy, Yewande Omotoso, Nawal El Saadawi, Panashe Chigumadzi, and Olumide Popoola.

Following its launch in London, Busby penned an essay for The Guardian UK in which she reiterates the importance of the anthology series.

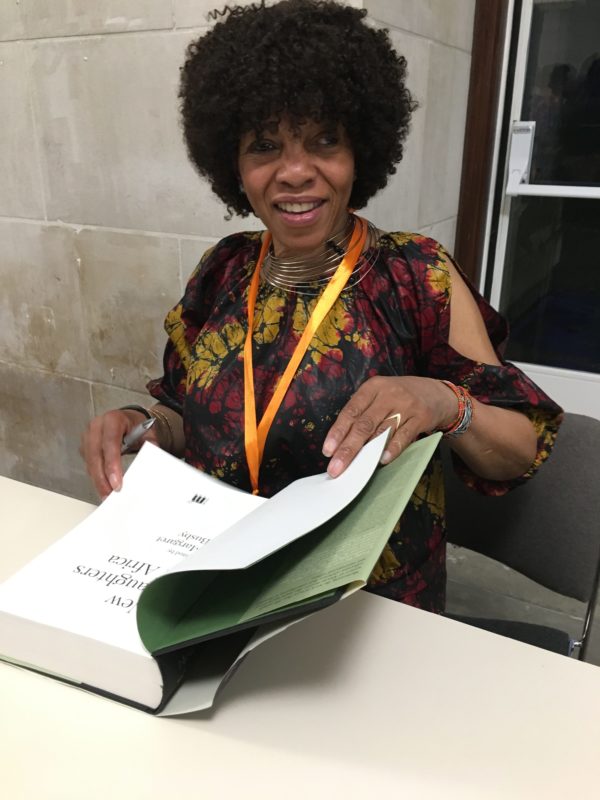

Hailed as the “Doyenne of Black British Publishing” by Blackhistorymonth.org.uk, Margaret Busby, a member of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), was born in 1944 in Accra, in then Gold Coast, “to parents with roots in Barbados, Trinidad and Dominica.” Her decision to co-found the publishing press Allison & Busby, with Clive Allison, in 1967, made her Britain’s youngest and first Black woman book publisher. In 20 years as Allison & Busby’s editorial director, she oversaw the publication of such significant books as Buchi Emecheta’s Second-Class Citizen, George Lamming’s The Pleasures of Exile, Sam Greenlee’s The Spook Who Sat by the Door, and C.L.R. James’ The Black Jacobins. Her press further brought to public attention the work of such names as Rosa Guy, Miyamoto Musashi, Val Wilmer, Michele Roberts, and Andrew Salkey.

Busby has since served as a judge for the Wole Soyinka Prize, the Commonwealth Book Prize, the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, the Caine Prize for African Writing, and the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. She is, at the moment, the Prize Ambassador of the SI Leeds Literary Prize and a patron of the Etisalat Prize for Literature.

Here is an excerpt from her essay.

*

Time was when the perception of published writers was that all the women were white and all the blacks were men (to borrow the title of a key 1980s black feminist book). At best, there was a handful of black female writers – Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Maya Angelou – who were acknowledged by the literary establishment. This was the climate in which, more than 25 years ago, I compiled and published Daughters of Africa. It was critically acclaimed, but more significant has been the inspiration that 1992 anthology gave to a fresh generation of writers who form the core of its sequel, New Daughters of Africa.

The critic Juanita Cox told me: “I received Daughters of Africa as a birthday gift from my father. Two things immediately struck me about the book. It was huge and it contained women like me. Even though I’d been brought up in Nigeria, I had had very little exposure to black literature. At school the only black characters I’d ever read about occupied the margins: figures like the Sedleys’ servant Sambo and the mixed-race heiress Miss Swartz in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. Daughters of Africa introduced me to a huge number of writers I’d never previously been aware of. And on a more personal level it made me realise that I was somehow valid. The anthology was peopled not just by women of ‘pure’ African descent, but also women of mixed ancestry, and just like the women the book contained, I too could have a voice.”

Ivorian Edwige-Renée Dro said: “It was as if the daughters of Africa featured in that anthology were telling me, their daughter and grand-daughter, to bravely go forth and bridge the literary gap between francophone and anglophone Africa.” Bermudian writer Angela Barry, meanwhile, spoke of her thrill at coming across a contributor whose father was from her island, allowing her to feel “that I also was a daughter of Africa and that I too had something to say”. Writer Phillippa Yaa de Villiers recalls: “We were behind the bars of apartheid – we South Africans had been cut off from the beauty and majesty of African thought traditions, and Daughters of Africa was among those works that replenished our starved minds.”

Read the full essay HERE.

New Daughters (Update) | Wadadli Pen July 06, 2019 10:52

[…] magazine, NB, Sussex Express, Trinidad Daily Express, Trinidad and Tobago Newsday, Brittle Paper, Brittle Paper, Young Voices, and The Turnaround […]