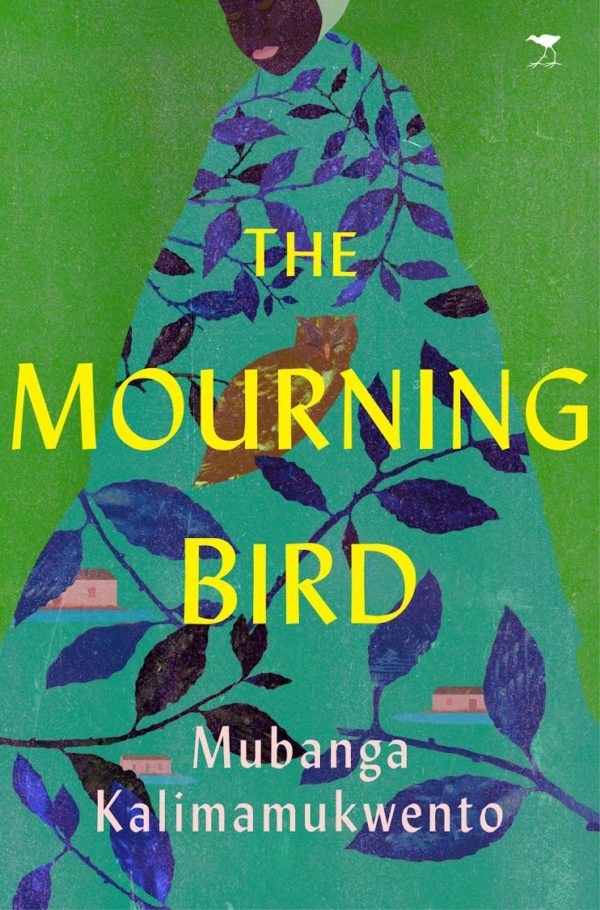

The Zambian writer Mubanga Kalimamukwento’s novel The Mourning Bird recently received the 2019 Dinaane Debut Fiction Award. In addition to the R35,000 prize money, her book will be released by Jacana Media on 1 June 2019 and will be “supported by Exclusive Books through its Homebru campaign.”

Here is a description of the novel:

When 11-year-old Chimuka and her younger brother, Ali, find themselves orphaned in the 1990s, it’s clear that their seemingly ordinary Zambian family is brimming with secrets, from HIV/AIDS, to infidelity, to suicide. Faced with the difficult choice of living with their abusive extended family or slithering into the dark underbelly of Lusaka’s streets, Chimuka and Ali escape and become street kids.

Against the backdrop of a failed military coup, election riots and a declining economy, Chimuka and Ali are raised by drugs, crime and police brutality. As a teenager, Chimuka is caught between prostitution and the remnants of the fragile stability that existed before her parents’ death.

The Mourning Bird is not just Chimuka’s story, it’s a national portrait of Zambia in an era of strife. With lively and unflinching prose, Kalimamukwento paints a country’s burden, shame and silence, which, when juxtaposed with Chimuka’s triumph, forms an empowering debut novel.

News of The Mourning Bird is timely, particularly given the interest in Zambian writing created by Namwali Serpell’s juggernaut novel The Old Drift, recently reviewed by Salman Rushdie, and efforts to animate the country’s literary scene with the founding of the Kalemba Short Story Prize.

In its April 2019 issue, The Johannesburg Review of Books published an exclusive excerpt from The Mourning Bird. Read part of it below.

_____________________________________________________________________

June 1997

I was learning that adults had two different sides. They showed the one that suited them at the time. I had come to accept this about my parents and other grown-ups I had known, except BoSitali. In our home, in Tate’s house, Bo Sitali was a patient teacher; she spoke slowly and rarely. Her words were kind and often funny. Between her broken English and thick siLozi, she often clashed with our mother, who found her to be too lazy and too slow and reminded her of these flaws many times. Bo Sitali cooked as many meals as Ma did, helped us get ready for school and agreed to play with me when I knocked off. Any game of my choice. Usually it was ciyato, after she finally taught me how to play. When she first came to our house, her skin was a deep, rich brown, smooth and even, and when she smiled, her teeth nearly sparkled against her black lips. She did not like to pray, not the way Ma did anyway, but agreed to go to church with us every Saturday and learnt the siLozi version of the songs we sang at church, even though she could not read. Her voice was deep and masculine, but when she laughed, it turned into a squeal. I became comfortable enough to call her my friend, though she was Tate’s youngest sister and, therefore, my aunt. It came as a surprise therefore that when we moved to her house, she was unrecognisable. She didn’t play games or laugh effortlessly. She showed no interest in my stories and had no patience for me. She was serious and busy, like all the other women I knew, like Ma. And her skin. She had bleached it a shade that had no colour, not quite orange, not quite brown, like an orange, hesitant to ripen—a sorry replacement for the rich, delicious black that adorned her before; only her knuckles stayed stubbornly dark, refusing to deny their former beauty.

My initial excitement about moving with her after Ma died quickly waned and I replaced it with an aching for my mother that I didn’t think possible until I had to nurse it every night. The Bo Sitali who was called Bamake Limpo—Limpo’s mother—by her neighbours, and Bo Ma Limpo (Limpo’s mother) by her husband, was a different one from the one I had grown up with. She had lightened her skin, but her knees and knuckles stayed dark, chocolate brown. She clicked her tongue and talked loudly with the other women in her neighbourhood. She gave sharp answers to my questions and reminded me as often as possible that her home was not my father’s house and I was to follow her rules.

That was not the first lesson we learnt though. The first lesson was that the stove was for decoration. On my second morning there, reeling from the whipping of the first night, I woke up before the cock crowed. I was going to cook Limpo some mealie-meal porridge for breakfast. As I forced the window open and pushed the curtain aside, I noticed Bo Humphrey hadn’t returned that night. He didn’t touch me at night, not when BoSitali was there, so I don’t know what prompted my asking.

‘Where is he?’ I wouldn’t let his name touch my lips.

‘Oh,’ she answered casually, ‘he had some work at the school, and they had to prepare for an event.’ She faked a yawn. It was the calmest she had spoken to me since I arrived.

Continue reading on The Johannesburg Review of Books.

Buy The Mourning Bird on Loot.co.za.

How to be a published writer in Zambia - or anywhere in the world - Ruth Hartley January 30, 2021 02:31

[…] Daniel Sikazwe very much or inviting me to take part with Mubanga Kalimamukwento, the author of The Mourning Bird. in this Writers Circle online forum. Mubanga and I have published our books in different ways […]