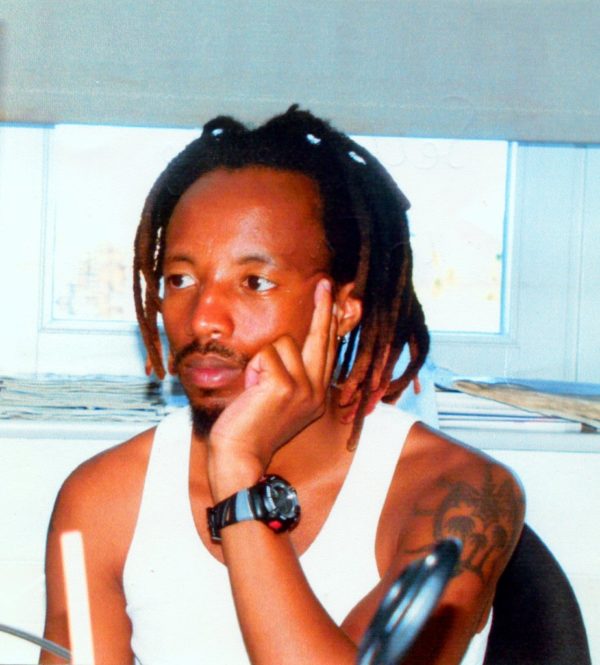

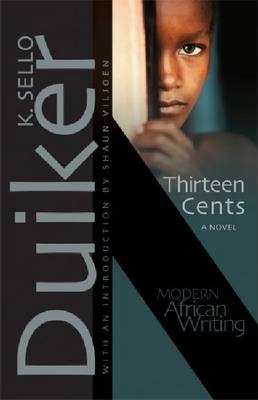

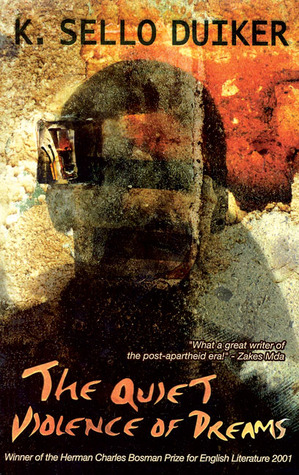

Kabello “Sello” Duiker, novelist, screenwriter, and one of South Africa’s most exciting creative voices, had a brief but widely impactful career. Born on 13 April 1974, Duiker studied journalism and art history at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, where he co-founded a poetry society called Seeds. He published two novels, Thirteen Cents (New Africa Books, 2000), which is written from the perspective of a Cape Town street child who experiences gangsterism and the sex trade, and The Quiet Violence of Dreams (Kwela Books, 2001), which follows a mentally troubled journalism undergraduate working in a gay massage parlour. Thirteen Cents won the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize for Best First Book, Africa Region, and The Quiet Violence of Dreams won the 2002 Herman Charles Bosman Prize.

In 2004, Duiker, then a commissioning editor at the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), suffered a nervous breakdown, resulting from his bipolar affective disorder. On 19 January 2005, aged 30, Duiker took his life. IOL News quotes a press statement from his family stating that it happened at a time “when he felt his mood-stabilising medication was taking too great a toll on his artistic creativity and joie de vivre.” His third book, the novel The Hidden Star, then unfinished at the time of his passing, was released by Umuzi Books in 2006. He would have been 45 this month.

Duiker’s books received acclaim for boldly tackling homosexuality, drug use, and sex work, and exploring subjugation, dispossession, and trauma. “He was a writer who wrote against the literary grain of his time and that is why he has earned a unique place in South African fiction,” Manosa Nthunya wrote in City Press, with the newspaper describing him as having “challenged our taboos and spoke truth to our trauma, leaving a lasting effect on the generation to follow.”

“His literature explored new themes that had up to that point not been dealt with by black writers,” Zakes Mda said of Duiker. “I genuinely admired him. What a beautiful human being. What a great writer of the post-apartheid era.” For his publisher and long-time friend Annari van der Merwe, Duiker was “fun-loving and enormously talented and perceptive. He was blessed with equal measures of gentleness and kind-heartedness on the one hand, and unflinching honesty and a fearless pursuit of what he saw as essential human experience on the other.”

Writing in The Guardian, Liz Mcgregor called him “one of the most promising post-apartheid writers, representing the frontier generation who attempt to transcend race in their exploration of South Africa.” Duiker, Niren Tolsi wrote for IOL News, was a “relevant and sensitive voice” and “stood out as a young writer who explored unconventional themes and confronted issues relevant to the new democracy.”

Duiker’s work, Edward Tsumele wrote for Sowetan Live, “heralded the arrival of a new crop of young black, bold and gifted writers.” Among creatives who have credited him as an inspiration, lists IOL News, are Siphiwo Mahala, Eusebius McKaiser, Barbara Boswell, Thando Mgqolozana, and Nakhane.

In The New York Times‘ profile of post-Apartheid fiction from South Africa, Rachel Donadio calls him “a rising star, anointed as a spokesman for his vexed generation.” Commenting on his mental illness, she wrote, “His suicide has come to seem a result of external as well as internal pressures,” a hint based on Fred Khumalo’s own suggestion: “Maybe in a way we killed him. We put him on a pedestal. We put pressure on him, we expected so much of him.”

“Duiker has created a vibrant cityscape populated by living, breathing, multifaceted human beings who seem a world away from the faceless Hollywood stock characters we see so often in depictions of African poverty,” Daniel Jose Older writes in his Times review of The Hidden Star: “Sure, magic ripples just below the surface of these moonlit streets, but first and foremost we learn about life in this neighborhood, the loves and losses and labors of its residents. It is neither idealized haven nor melodramatic hellscape, but something much more alive. Simply put, it’s a home.”

In its most recent issue, for April 2019, The Johannesburg Review of Books published an illuminating conversation remembering Duiker, between Bongani Madondo, who has been Duiker’s friend, and Rofhiwa Maneta. “I read his literary body of work as a response to the still unexplored space between mental illness, spiritual healing and sexuality,” Madondo said. “The Quiet Violence of Dreams is in conversation with the other books—and is an extension of Thirteen Cents.”

Asked about reports that Duiker had a mystic calling, he said: “Kabelo never confided to me that he was considering training to become a direct healer, iSangoma, beyond the healing his writing already performed. But if he ever arrived at that stage in the journey of his soul, I would not be surprised. I will cherish his smouldering talent and his discipline to see a project to its end forever.”

The South African Literary Awards has a category named in his honour: the K Sello Duiker Memorial Literary Award, for novels and novellas by writers who are 40 and under, which has been won by, among others, Zukiswa Wanner, Panashe Chigumadzi, and Nthikeng Mohlele.

Rest in power, K Sello Duiker.

Remembering K Sello Duiker, great writer of South Africa’s post-apartheid generation | Gunduzi Online Solutions December 19, 2023 00:26

[…] This article was originally published in Brittle Paper. […]