Chimurenga has released its April 2019 issue of The Chronic. Themed “Who Killed Kabila II,” the issue is built around the assassination of Laurent-Désiré Kabila, president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on 16 January 2001. A sequel to their sold-out December 2017 issue of the same name, “Who Killed Kabila II” uses the rumours around his killers—the question of who actually killed him—as “the starting point for an in-depth investigation into power, territory and the creative imagination by writers from the Congo and other countries involved in the conflict.”

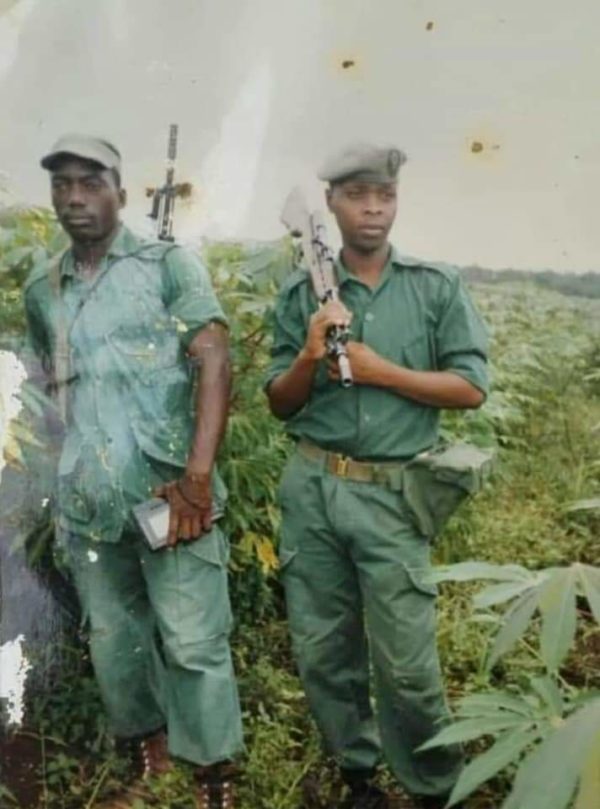

On January 16, 2001, in the middle of the day, shots are heard in the Palais de Marbre,the residence of President Laurent-Désiré Kabila. The road bordering the presidential residence, usually closed from 6pm by a simple guarded barrier is blocked by tanks.

At the Ngaliema hospital in Kinshasa, a helicopter lands and a body wrapped in a bloody sheet is off loaded. Non-essential medical personnel and patients are evacuated and the hospital clinic is surrounded by elite troops. No one enters or leaves. RFI (Radio France Internationale) reports on a serious incident at the presidential palace in Kinshasa.

Rumor, the main source of information in the Congolese capital, is set in motion…

18 years after the assassination of Laurent-Désiré Kabila, rumours still proliferate. Suspects include: the Rwandan government; the French; Lebanese diamond dealers; the CIA; Robert Mugabe; Angolan security forces; the apartheid-era Defence Force; political rivals and rebel groups; Kabila’s own kadogos (child soldiers); family members and even musicians.

The geopolitics of those implicated tells its own story; the event came in the middle of the so-called African World War, a conflict that involved multiple regional players, including, most prominently, Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe.

As this research revealed, who killed Kabila is no mystery. It is not A or B or C. But rather A and B and C. All options are both true and necessary – it’s the coming together of all these individuals, groups and circumstances, on one day, within the proliferating course of the history, that does it.

“Who Killed Kabila?,” the editors of Chimurenga explain, is “the result of a three-year research project that included a 5-day intervention and installation at La Colonie (Paris), from December 13 – 17, 2017, which featured a live radio station and a research library, a conceptual inventory of the archive of this murder – all documented in a research catalogue.”

As is their trademark, Chimurenga is using this issue to subvert ideas about storytelling: it is inverting the popular idea of “the single story,” adopting it as an intellectual tactic and exploring its power. The issue, “conceived as a sebene of the Congolese rumba,” is also exploring music—Congolese music: its potential, its imagination—as a medium capable of capturing history.

Telling this story then, isn’t merely a matter of presenting multiple perspectives but rather of finding a medium able to capture the radical singularity of the event in its totality, including each singular, sometimes fantastical, historical fact, rumour or suspicion. We’ve heard plenty about the danger of the single story – in this issue we explore its power. We take inspiration from the Congolese musical imagination, its capacity for innovation and its potential to allow us to think “with the bodily senses, to write with the musicality of one’s own flesh.”

However, this editorial project doesn’t merely put music in context, it proposes music as the context, the paradigm for the writing. The single story we write borrows from the sebene – the upbeat, mostly instrumental part of Congolese rumba famously established by Franco (Luambo Makiadi), which consists in the lead guitarist playing short looping phrases with variations, supported or guided by the shouts of the atalaku (animateur) and driving, snare-based drumming.

In line with Ousmane Sembene’s use of multi-location and polyphony as decolonial narrative tools, the issue features “writers from the countries directly involved and implicated in the events surrounding Kabila’s death (DR Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Angola, and a de-territorialised entity called AFDL) to write one story: the assassination of Kabila.” The contributors—Yvonne Owuor, Antoine Vumilia Muhindo, Parselelo Kantai, Jihan El-Tahri, Daniel K. Kalinaki, Kivu Ruhorahoza, Percy Zvomuya, and Sinzo Aanza—work with fact and fiction to interrogate the event-scene of the shooting as “their starting point to collectively tell the single story with its multiplication of plots and subplots that challenge history as a linear march, and tell not the sum but the derangement of its parts.”

The methods employed in “Who Killed Kabila?,” the editors explain, is an imaginative remapping: one that “better accounts for the complex spatial, temporal, political, economic and cultural relations at play, as well the internal and external actors, organized into networks and nuclei – not only human actors but objects; music; images; texts, ghosts etc – and how these actors come together in time, space, relationships.”

Last year, Chimurenga received the Vera List Center for Art and Politics’ 2018-20 Jane Lombard Prize for Art and Social Justice.

Get the print ($35) and digital ($10) copies of “Who Killed Kabila II” on Chimurenga’s website.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions