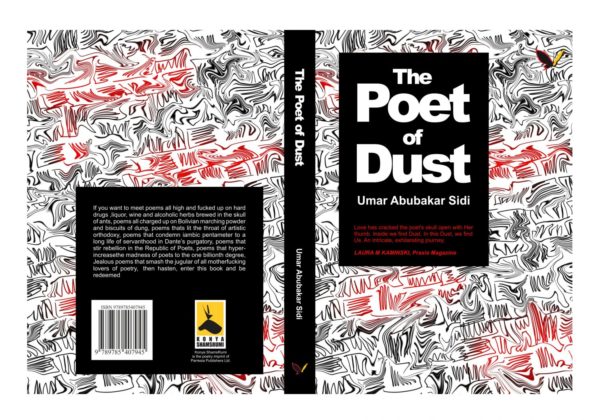

Umar Sidi is a helicopter pilot with the Nigerian Navy. He is the author of Striking the Strings, the poetry chapbook The Poet of Sand (Saraba) and the poetry collection The Poet of Dust (Konya Shams Rumi). His work has appeared in Brittle Paper, Transition Magazine, and elsewhere.

In this edition of #PoetryTalk, Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike chats with Umar Abubakar Sidi about his interests in mysticism, Sufism, the Beat Generation Poets, angels and demons, and mad poets.

***

Umezurike

Can you say a little about why you changed the title from The Poet of Sand to The Poet of Dust? Your first collection is restrained and self-contained. But The Poet of Dust is intense, a rush sweeping waters! That’s the image that came to mind while I was reading it. What inspired The Poet of Dust? What made you go for this tone and form? How do you think that impacts how you write?

Umar

I strongly believe that a poet is a metaphysical being who penetrates to the depths and in so doing keeps solidarity with others. In this sense, poetry becomes a means for the exploration of eternal human anxieties. In The Poet of Dust, I assumed the role of a drunken Sufi and a holy mad man to navigate the dark, the hidden and the mysterious pathways of thought. I also employed the language of conscious ambiguity to synthesize between dissimilar images in order to provoke and agitate. The Poet of Dust could be described as a meditation on metaphysics, the connection between, body, soul and spirit and the very nature of poetry itself. Perhaps, the note and form in the collection were partly influenced by my desire to seek the transcendental, which is the single objective of my engagement with poetry, especially when I was writing The Poet of Dust. To seek the transcendental, I immerse myself in the pool of feeling which I imagine to be fluid, fully immersed I court delirium, ecstasy, hallucination, drunkenness, illumination and bliss. After emerging out this pool, I try to recount this experience on paper. For me, writing, that is putting pen to paper comes at the very last stage and it is the least important.

Umezurike

Unlike Striking the Strings where the poems are sparse, The Poet of Dust is expressive and a little irreverent, given that you are coming from a background where poetic license is mediated by fear of censorship. How did you manage that?

Umar

Intoxication. Drunkenness. I got high on the dope of poetry. In experiencing the poems in The Poet of Dust, I unconsciously don the garb of the holy madman and assumed the role of a dervish, particularly a drunken Sufi. Drunkenness and madness have always offered mystics cloaks in which they hide or reveal their true selves. With drunkenness the spirit becomes ecstatic, illuminated, light feathered, and free. With madness the soul negotiates dangerous and dormant pathways of thought and as a result it is able to think the unthinkable and utter the unutterable all in a bid to seek the hidden and the transcendental. In this state there is no question of fear. There is only revelation, reverie and freedom. I have always been fascinated by drunken mystics and mad poets: they tend to utter the most profound of truths. El- Hallaj, Laikhur, and the Zen Master Ikkyu are a few examples.

Umezurike

Your influences range from Martin Espada, Adonis, Darwish, Simic, Rumi, Billy Collins, and

the Beat generation poets like Allen Ginsberg, Neal Cassady. What fascinates you about these poets? What poets were important to you when your first started writing? How much Sufism influence is in your poetry?

Umar

I am still an informal member of the Kano School of Poetry, or what I like to call the Ismail Bala School of Poetry. This is a group of poets unofficially led by Ismail Bala, who are living their lives and writing poetry. I discovered them when I was idling after I graduated from the Nigerian Military School, and I glued myself to them. I followed them everywhere; on the internet, on the pages of newspapers, in journals and in dreams.

Meeting these poets was and is still very instructive to me. Before then, there was Muhammadu Bello, popularly known as Katib, the writer. He is a poet, a grammarian, a philosopher, a mathematician, a programmer, and a novelist; in fact, he is a polymath of some sort. Katib was my tutor when I was about 8 or 9 years of age in Sokoto. He taught us, his pupils, the rudiments of poetry in the ajami tradition, including the techniques of composition, the categories of silence and the many methods of listening. Some years ago, Origami issued his debut Hausa novel, Rudanin Tunani. It is a hallucinatory philosophical novel written in the style of Ibn Tufail of Philosophus Autodidactus fame.

I am in constant interaction with poets both the old and the new. From Adonis I learnt boldness and courage. Adonis restored back the dignity of Arabic poetry to its pre-Islamic notions where poetry is thought and thought is poetry. He stretches the possibilities of poetry by sacrificing meaning for striking metaphors. He stands out as the universal prophet thundering the exhortation: the key to the soul of man is poetry, the key to the soul of nature is the soul of man. For me, Adonis is the greatest poet alive. He is a living god. Allen Ginsberg and the Beat Generation Poets were rascals and holy desperados who created a kind of counterculture. Somehow, being a soldier venturing into the literary community I considered myself a kind of misfit, someone coming from the fringes, I needed some kind of illumination and guidance so, Ginsberg and his gang served as lamp posts and led me through.

As for Sufism, it is the foundational structure holding the architecture of my poetry. An understanding of Sufism is required for a reader to have a meaningful engagement with my poetry. Because of their insistence on experiencing the Absolute here and now, the Sufis have created a new language and a new vision. I am fascinated by their prescription that the path of love is the only path to God or the Absolute. I am intrigued by their insistence on the unity and oneness of being, which negates identity, suppresses the ‘other’. I suspect that poetry is the only ‘vessel’ able to accommodate the abstract and distractive features of Sufism in its search for the Absolute.

Umezurike

In ‘Poetic Manifesto’ the speaker emphasizes why “we need poems.” But in this day and time of deep fear and direct hate, how much can poetry do?

Umar

Poetry speaks to the highest in us. It transports us to the source of feeling within us where there is emptiness, nothingness and love. We need more poetry now more than ever. What I feel is more important is not only about reading poetry, but about serious and conscious engagement with it. We need to develop a ‘poetic outlook’ of the universe and redefine our place in it. This would enable us to arrest fear, hate and embrace the beautiful things that make us human.

Umezurike

Toni Morrison said in an interview that writers are holy. In “The Peninsula of Poets,” the speaker in the voice of Ginsberg says, “A Poet is a holy fool.” So, to you, who is a poet? What is poetry to you? And what defines a poem as a poem for you?

Umar

My best answer would have been ‘I don’t know what a poem is’ but that would have been quite dishonest. Perhaps I know a bit about poetry but I don’t know how to define it. For this reason I won’t define, but I will attempt to describe. The inimitable Borges is of the opinion that language is unnatural to the human species. What is natural to humans is feeling. Language is an artificial necessity we invented in order to express feeling. Poetry, I believe, is a propellant, or a vehicle which takes humans back to the pools of pure feeling. So, primarily poetry is not about language, poets use language and its associated components to evoke feeling. A poem, therefore, is that which seeks return and union, that which takes man back to the point of primordial origin. In this sense, every poem is mystical and every poet a mystic.

Umezurike

There appears to be a burden of tradition for many Nigerian poets to write poetry that tends

towards the didactic. What is your experience of writing outside this tradition?

Umar

I am not very much aware that I am writing outside any tradition. I am just catching fun and

always pursuing new ways of archiving my experiences. But, I became aware, at some point that there is an indescribable joy that comes with exploring the possibilities of experimentation, there is almost a rapturous and exhilarating delight in treading on dark and mysterious pathways of thought, there is always a perplexing and enchanting satisfaction associated with going outside oneself, all in a bid to seek the new and the hidden. Poetry is not to be imprisoned within the cage of any tradition; it is not to be caged even in its own tradition, to do that is to do the sacrilegious, and the consequences, to say the least, are disastrous. It means, in simple terms, stagnation and death for society and mankind. I share Adonis’s view that development is not achieved only through scientific and technological advancement; it is achieved more importantly through the development of the human spirit. And what better way is there to facilitate the development of the human spirit than through poetry? But can the spirit develop when poetry is caged? By spirit, I am referring to our intuitive and contemplative faculties.

Umezurike

How do you go about writing a poem? For instance, ‘Seven Days to the End of the World’?

Umar

This depends on a variety of things. There are times when I get immersed totally into an imaginary pool of feeling or what I like to call ‘source of poetry’. And there are times when it appears as if I am receiving dictations from angels, demons and even oracles. As for ‘Seven Days to the End of the World’, it came one morning on a working day. I was putting my duty reports together when an idea struck me: what will happen a week before the end of the world? I meditated and after that I wrote something down. Sometimes, I like to think that the poem was dictated by an angel.

Umezurike

Love recurs in much of your poetry. Why is it such an important theme for you?

Umar

I love love. I love to love. I have always believed that love is one of the most important aspects of being human. If we can learn to love genuinely, we may be able to annihilate the ‘I’, obliterate the ‘Other’ and attain ‘Oneness’. I also believe that through love we can understand ourselves and our place in the universe, through love we can make sense of the mysterious dimensions of life and discern the magical and enchanted aspects of our complex reality.

Umezurike

In Striking the Strings I noticed a strong reference to the luminaries, sky, clouds. Was this preoccupation influenced by your profession as a pilot?

Umar

Well, I am not very sure about that. What I am sure about is that I have always been bewildered and enchanted by the heavens and I used to have a secret ambition, as a child of wanting to become an astronaut.

Umezurike

You began and ended the collection ‘Striking the Strings’ with a meditation on ‘beginning and end’, what informed this approach?

Umar

Perhaps, I wanted to give the reader something to think about, to point the reader to the notion that ‘the beginning is poetry, the end is poetry’. Perhaps, I was thinking of the cyclical nature of reality, where it is presumed that the end is the beginning of another cycle, and the beginning the end of another cycle and so ad infinitum. May be this also has a bearing on what Billy Collins wrote in his poem The Trouble with Poetry. The trouble with poetry, according to him, is that it inspires the writing of more poetry, the end of one poem signals the beginning of another. Perhaps, this is why poets are miserable fools who are entangled in an infinite portal of poetic continuum.

Umezurike

Do you feel that “A poet is a blind artist painting upon/ The invisible mirrors of the sky”?

Umar

Yes, absolutely.

Umezurike

Do you think that poetry can really “stir passion in /in schizophrenics, lunatics, mental patients”?

Umar

“Instruction to a Poet,” the poem from which these lines are taken from is simply a call to the poet to seek the highest in him and seek ways of speaking (probably through poetry) to the highest in others including of course the mentally challenged. So I suspect there is some kind of poetry that could stir passion in schizophrenics, lunatics and mental patients. And I want to ask, aren’t all writers some kind of lunatics, isn’t there schizophrenia in the creative process?

Umezurike

Many an artist is often tormented by images-even sounds-that are too ineffable. How do you cope with “the disturbing claptrap of dumb demons arguing in your own mind?”

Umar

I love demons. They are the most reliable facilitators of the creative process. Intercourse with demons however depends greatly on inclination to artistic reception at the time of contact, and of course the severity or intensity of the demonic influence. Some are so powerful; they wrestle their victim to the ground and consume him.

Umezurike

Tanure Ojaide once branded the new generation of Nigerian poets as “copycats”. Do you agree that the current generation lacks originality and ideological depth. Can you say a few words about the current state of poetry in Nigeria?

Umar

I strongly feel that to call a whole generation of poets “copycats” is unfair. You mentioned ideological depth, yes. I do agree that some measure of penetration or immersion into the depths of something is required for one to experience serious poetry and I see that a lot of that is happening currently. There are many assured and promising voices sprouting all around. However, the ambiguity of spoken word poets or artiste is almost choking the literary space. The disturbing thing about some of these guys, especially the younger ones is that when you subtract the ‘theatrics’, the poems appear dead due to absence of depth and rigor.

********

About the Interviewer:

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

Abdulmalik Mahmud July 30, 2024 05:27

I Read and fall in love with all his responses, I feel like he sat with me and heard from the depth of my back's back before the interview. His conclusions, show the depth of his knowledge of poetry(as a sinful act) and the vivid depiction of a poet as just a sacred sinner. He further emphasises that poetry is must-needed tool to properly understand the demons and angels around us and around the world we live in. The following paragraph clearly supports my surmise: _"We need to develop a ‘poetic outlook’ of the universe and redefine our place in it. This would enable us to arrest fear, hate and embrace the beautiful things that make us human."_ What also fascinates me from the interview is his critical and in-depth check of the current status of the Nigerian spoken word artists. Where he asymptomatically conveyed the load weighing down his heart. Where he said: _"However, the ambiguity of spoken word poets or artiste is almost choking the literary space. The disturbing thing about some of these guys, especially the younger ones is that when you subtract the ‘theatrics’, the poems appear dead due to absence of depth and rigor."_ Finally, Sidi is just a revolutionary author, a true definition of a sacred sinner (poet) and the only living god in our world. I read every collection/novel (book) he has published not a month away from the lunching. His irrationality forcibly pulls me to be checking up on his move, every now and then, and become gluily keen to his scribblings.