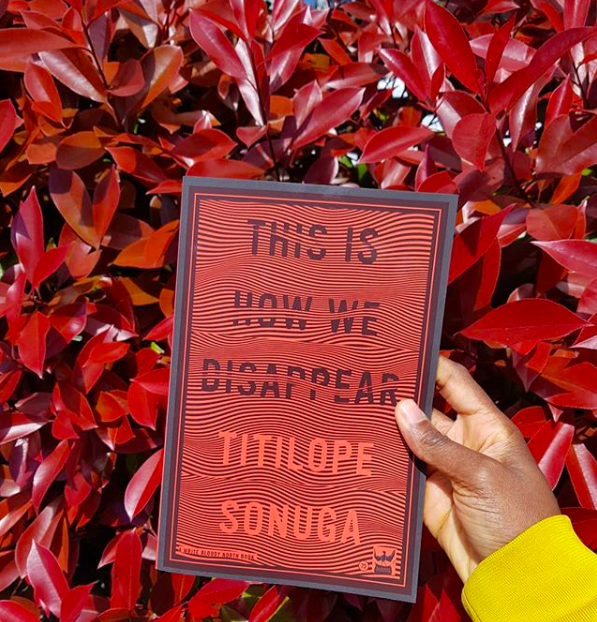

Nigerian-Canadian poet, writer, and performer, Titilope Sonuga is the featured guest of this week’s #PoetryTalk interview series. We discuss her long-awaited poetry collection, This is How we Disappear, Chibok girls, womanhood, female victimization, and poetic form.

***

Titilope Sonuga

Titilope Sonuga is an award-winning poet, writer and performer who calls both Edmonton, Canada and Lagos, Nigeria home. She was the winner of the 2011 Canadian Authors’ Association Emerging Writer Award for her first self-published collection of poems, Down To Earth. Her second collection Abscess was published in 2014 by Geko Publishing (South Africa). Her work has appeared in Brittle Paper, The Great Black North: Contemporary African Canadian Poetry, was translated into Italian for El-Ghibli Magazine, and into German for the Berlin International Poetry Festival. Her latest collection is This is How We Disappear.

Umezurike

How did you come about the title This is How We Disappear? What was your experience while writing this collection? Did you visit any internally displaced people camps?

Sonuga

I wrote a poem a few years ago titled “Hide and Seek” about the disappearance of the Chibok girls, the killings of the Bun Yadi boys, and the ways in which the most horrific incidents of disappearance and erasure, particularly in Nigeria, were being treated like a game of hide and seek. The collection began there, with those questions, but began to expand into a wider exploration of the disappearance of women, both in the literal and metaphoric sense. I was reading recently about the famous magic trick in which a woman in a box is sawed in half. There are many arguments about which magician first performed the trick and almost none about who that first woman was in the box, risking everything to be there. It falls right in line with the many erasures of the labour of women in the world. I think it is fascinating that much of the work of that trick happens right there in the box, below the surface, with the woman negotiating her body in order to emerge unscathed. The title for the collection was born there, in a desire to explore disappearance as an act of survival; shape shifting in order to escape the boxes we are placed in. The collection is an exploration of disappearances but also a celebration of these instructions for survival passed on through generations.

Umezurike

The collection gives “voice” to the silenced voices of the Chibok girls and their parents. Much of the poetry orbits around female victimization and death. What role does poetry play in a society where there remains “thousands more, missing and murdered”?

Sonuga

It might appear on the surface that the poems orbit around female victimization and death, however my intentions for the collection are quite the opposite. The poems sit in conversation with each other as a way to highlight how women survive and thrive in spite of the obstacles often stacked against that very act of survival. The collection is about our small and large acts of resistance, how we choose life, how we are the architects of our own joy even in the face of death. I’m weary of saying that the collection gives “voice to the silenced voices…” because it is impossible for me to do that. What I have are many questions, and what might emerge is a desire to take a closer look at the things that are happening right there in front of us so that we might inch closer to some version of understanding and perhaps healing. Poetry for me is less about the impossible task of being a voice and more about an excavation of hidden things. With poems I dig up one question and pull out the next, hold up one mirror and find another reflection. Through this process of pulling, perhaps on the other end, something that looks like an answer.

Umezurike

“We are Ready,” and “After” address the political moods in the nation. In the former, you paint a sunny portrait of optimism and people who “bloomed defiant across the country,” but in “After,” the portrait is dismal, and the people, now disillusioned, are “searching for answers that do not come”. What do you think is the relationship between art and politics?

Sonuga

The desire, ability or determination to create when it feels like the world is on fire is inherently a political act and whatever we create is stewed in what feels most urgent about the world we live in. The work of artists generations over has always served as a living archive of the times, has always been the most honest reflection of who we were and what we felt. Art, created with the purest of intentions, is a sacred place in which the truth about us can sit undisturbed. It is perhaps what makes artist so dangerous to the powers that intend to obscure that truth.

Umezurike

Chris Abani says that, “poems invite you to step in and step out.” What is poetry to you? How do you decide what form a poem like “The Girl Comes Back with fire in Her Chest” would take? When do you decide that a poem is ready enough to be performed on stage? Are there times you improve on a poem you have already performed, having found out that the desired effects didn’t come through?

Sonuga

Poems are an endless digging, into deeper questions, into a deeper truth. “The Girl Comes Back with Fire in Her Chest” is a poem that has bounced from page to stage and back again. Somewhere in that bouncing it found its form. I consider it an added privilege to perform my work because it allows for an even deeper edit once the poem has been polished on the page. Sometimes the poem is shifting with each new performance of it, which is exciting to me also. I know when a poem is ready when it feels ready to me, when it feels settled in my body when I say the words out loud. There is no desired effect because the audience is always changing. The effect of one poem changes from room to room, so it becomes a really unreliable way of gauging the value or quality of a poem. I start first with the intention and I thread that through as I continue to work on the poem. I decide if it will remain on the page or if I wish to move it into performance and I check, with every iteration, if my intentions are intact, and if I can stand behind them no matter where the poem is read or performed.

Umezurike

Redefining African womanhood has been a preoccupation of African women writers, and as a mother, how do you relate to issues of “women who offer up their bodies/ into the belly of the beast/ to protect their children”? What insights has poetry offered you on questions of female bodies and black bodies, as reflected in “Trigger Warning,” and “Home going” and “Vanishing”? Can you expand on the place of feminism in your work?

Sonuga

I am not sure that it is redefining as much as it is a radical truth telling about the many forms we have always taken, that have over the years been dulled down to a single narrative. Literature in general offers really beautiful insights into who we always were, we realize through art that feminist ideas are not brand new. What we might have now is a more complex language and a more nuanced vocabulary for ideas that have always existed but have been erased or disappeared. Motherhood has simultaneously softened and strengthened me. It has allowed me to look with a measure of grace at the choices my mother and her mothers before her made and to celebrate those choices as acts of survival, to accept those choices as valid too. That is, for me, at the heart of feminism both in and outside my work, choice. I have been for many years preoccupied with the body in my work; how we move through a room, how we move through the world, how the world moves through us. Black bodies, black female bodies, the violence that those bodies have endured for hundreds of years make it truly remarkable that we exist in the brilliant ways that we do. It brings me joy to write poems that attempt to return those bodies to their sacred place.

Umezurike

What inspired “This is How You Heal the Wound”? Can you talk a little bit about it?

Sonuga

This is “How You Heal the Wound” was written as an instruction for healing passed down through generations as you might a family recipe. Something short, and sweet and true that you might whisper like a prayer to be remembered when the pain is at its most blinding.

Umezurike

I’m aware that you have collaborated with a couple of poets and artists. Could you describe what drives you to undertake such collaborations, and to what ends? Are there challenges you faced and how did you deal with them?

Sonuga

Creating can be such an isolating process, so it always feels good to me to bring the work out of that place and into the experience of creating with someone else or giving that work to an audience. It is why performance is so special to me, it allows me to come out of my own head and back into the world. It is always illuminating to see how other artists work and to grow from that in my own work. Beneath the surface of most challenges in artistic collaborations is the ego. The more I have practiced the more I am able to wrestle the voice of the ego into the truth. I never want my desires about how I believe a thing should be to rob me of the simple enjoyment of playing, of creating something spontaneous and true and just letting that be exactly what it is.

Umezurike

The poems are mostly grim, but affecting nonetheless. I would love you to talk about “No Place Left to Bury the Dead”:

What do we do with the bodies?

How do we gather them up

to know which arm goes where?

Sonuga

I think grimness is a luxury afforded those to whom these stories are not an everyday reality. I wrote “No Place Left to Bury the Dead” (originally titled What Do We Do With All These Bodies) after the Boko Haram bombing in Nyanya, and after Natalia Molebatsi’s poem “After The War.” I was thinking then about how commonplace these incidents had become and how we had begun to lose track of which one was which, and was it fifty people or two hundred, or was it a thousand and ultimately, who was going to answer for all these bodies and gather them with the grace they deserved.

Umezurike

What is your earliest poetry memory? How did you come into poetry? And when? What motivated you to take to spoken word poetry?

Sonuga

The first time I considered that I might know how, or want to know how to write poetry was in grade 10. I wrote a poem for an English assignment about the civil rights movement and something about the way my teacher and the people who read it responded to it made me realize that there was something there. I went on to study engineering, but poetry and literature in general became a kind of safe place. I discovered spoken word years later and began experimenting with performance around 2007. I then went on to found a spoken word collective and weekly open night in Edmonton in 2009 and to compete in local and national slam poetry competitions. I quickly discovered I did not have the heart for slam but I fell in love with the stage and continued to grow in that direction.

Umezurike

Spoken word poetry seems to be all the rage in Nigeria, especially in Lagos, Abuja, and Port Harcourt. How do you account for the emergence and vibrancy of this phenomenon? Would you say spoken word poetry has inspired a sort of bandwagon effect, where everyone aspires to become a spoken word artist?

Sonuga

I think it’s quite beautiful to witness the momentum the art form has taken across the country. Particularly in these times, it is exciting to hear young people speaking their minds and telling their truth. The barriers for entry are quite low, you don’t need a certificate to declare you a spoken word artist, you simply do and then you are. That is what makes it exciting but also what make it difficult to negotiate the quality of the work against the quantity of it. I try to be careful in my assessment of the bandwagon effect you mentioned. I think it is beautiful that people are inspired to try their hands at it, what is needed is space and time to grow, to improve, and more opportunities for learning. The more spaces we can create for people to move out of a place of imitation into their own authentic voices the more the art form will grow.

Umezurike

Can you talk a little about what you think might be the distinction between spoken word and written poetry? How do you navigate these genres of poetry? Do you think they perform different roles? What are the challenges of writing in spoken word and how do you cope with them?

Sonuga

This is a question that comes up often, and usually in circles where the need to make this distinction is an attempt to value one over the other. What we are seeing now is poets blurring the lines, existing on the page and on the stage. Winning awards and prizes in both arenas, putting out best sellers and selling out live performances, because ultimately, the audience does not care. They just want to feel something. In my mind, the only true distinction is that one is written and the other is spoken. All of my work begins first on the page and then it becomes a choice of whether to move it further or not, the birthplace is the same. They perform different roles in the same way that you might choose to listen to an album or watch a live concert. Each holds its own magic, each requires its own skill, and each hold value for the listener.

Umezurike

Speaking of poetic influences, are there writers who have had an impact on your poetry? What poets do you read these days?

Sonuga

The genius of Toni Morrison and Sonia Sanchez and Maya Angelou, the music of Lauryn Hill and Nina Simone and Sade Adu. The words, the words, the words of Lynne Procope, Rachel Mckibbens, Dominique Christina, Aja Monet, Bassey Ikpi, Warsan Shire, NoViolet Bulawayo, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and on and on and on, really just to say that it is women, existing in their power, in their work, that makes me feel most honoured and inspired to touch a page.

Photos via Titilope Sonuga’s Instagram page | @titilope

Buy This is How We Disappear | Here

********

About the Interviewer:

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

8 Must-read Expository Interviews with Prominent African Writers - EBOquills April 04, 2020 09:32

[…] Poetry is the excavation of hidden things, Interview with Titlope Sonuga: How do you define poetry as a poet? In reading other poets’ definitions of poetry, my […]