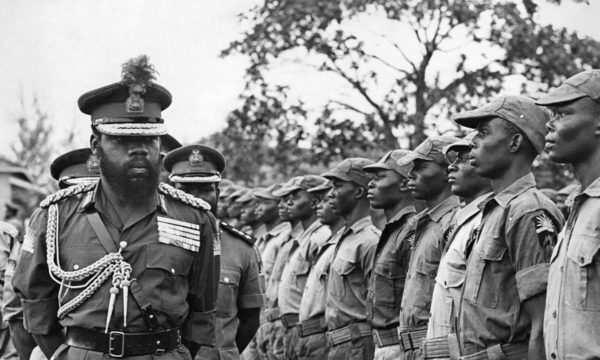

Every May 30, Nigerians remember the Biafran War, the 30-month conflict between the Federal Government of Nigeria and the secessionist state of Biafra, which lasted from 1967 to 1970 and left millions of mostly Igbo and then Eastern Nigerian origin dead—not only from the fighting but also from the blockade-induced starvation. Also referred to as the Nigerian Civil War, its massive cost has been the subject of books: Chinua Achebe’s collection Girls at War and Other Stories (1972) and his memoir There Was a Country (2012), Wole Soyinka’s memoir The Man Died (1971), Elechi Amadi’s Sunset in Biafra (1973), Flora Nwapa’s Never Again (1975) and Wives at War and Other Stories (1992), Chukwuemeka Ike’s Sunset at Dawn (1976), Cyprian Ekwensi’s Survive the Peace (1976), Buchi Emecheta’s Destination Biafra (1982), and more recently, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun (2006) and Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Trees (2015).

Writers remembered the War in essays and on social media. (Scroll past the tweets to see the essays.)

Today marks the anniversary of the declaration of the Republic of Biafra. May 30, 1967. I keep two framed Biafran pounds on my desk to remind me every day. #BiafraRemembranceDay pic.twitter.com/hUicjg0Ldu

— Nnedi Okorafor, PhD (@Nnedi) May 30, 2019

#Ozoemena May we never forget the sacrifices , big and small , made for us by those who believed #Biafra #genocide

— chika unigwe (@chikaunigwe) May 30, 2019

On this day in 1967, Biafra was declared in the heat of the conflict that led to the war in which over 2,500,000 Igbo lost their lives. It is just disappointing that Nigeria as a country has decided that this immense loss of lives isn’t worth a memorial. But then we the Igbo, … pic.twitter.com/jaRPZrMioX

— Ebenezer Agu (@EEZER_06) May 30, 2019

For the Republic of Biafra, May 30, 1967

———————-

I had an uncle. BBC. BBC, that’s what we called him. We called him BBC because during the Nigerian civil war he would always assure us that the war would soon end and Okokon Ndem, Von Rosen and Biafra would soon end in hell-fire. pic.twitter.com/daiPK0sGv6— Pa Ikhide (@ikhide) May 30, 2019

Also, I touched on Biafra in comic series/graphic novel LaGuardia, too. Of course, in the future, things get even more…complicated.

pic.twitter.com/DtXrgS6WKt

— Nnedi Okorafor, PhD (@Nnedi) May 30, 2019

DATABASE OF BIAFRA WAR VICTIMS AND SURVIVORS

In another decade, all those who were 18 years at the start of the Biafra War would be approaching their 80s. Many would be dead.

The clock is ticking. There is great urgency to document all the memories that can still be remembered. pic.twitter.com/cWGw1RLO9V

— Centre for Memories (@cfmemories) May 27, 2019

On May 9, Okey Ndibe reflected on the War in a piece titled “Death Was Around the Corner.” It appeared on Biafran War Memories, a digital archive for first-hand accounts of the War, created by the journalist Chika Oduah. “We never stayed in relief camps. We found homes, you know, which—the first place we moved, Ezinifite—we stayed with the family of a woman who was my mother’s friend and classmate in teacher training school, so we stayed with their family,” Ndibe writes. “Subsequently, when we moved to other places we rented typically a room. So all seven of us would be packed in one room because there wasn’t much accommodation at all, so people sacrificed and people just gave refugees, as we were called, a room. Sometimes we were lucky to get two rooms. But often I remember just staying in one room with a kind of a cloth divider dividing where my parents slept and where the kids, five of us, slept and sometimes joined by my cousins as well.”

Emmanuel Iduma, author of A Stranger’s Pose and editor of Saraba, wrote an essay for The New York Review of Books titled “‘Gone Like a Meteor’: Epitaph for the Lost Youth of the Biafran War.” In it, he notes the experiences of three men who died in the War: connecting those of the poet Christopher Okigbo and the Kenyan photographer Priya Ramrakha, and remembering an uncle he is named after. Here is an excerpt below.

________________________________________________________________________

The books published about the war, by memoirists on either side, are written from the perspective of those who survived, and can manage to speak of its horrors. The dead, voiceless, keep to themselves. And what of the unborn? When I remember my uncle, it is to grieve for a man whom I never knew, forty years after his death.

Christopher Okigbo, a poet, and the Time-LIFE photographer Priya Ramrakha both died in the Biafran War. The men never met each other but shared a setting for what would be the final labor of their lives. Like my uncle, they, too, died young: one at thirty-four, the other at thirty-three.

Ramrakha had taken photographs of conflict zones all over the world—dead Mau Mau fighters in Kenya, mourners after a riot in Djibouti, casualties of a British attack in Aden—but his obituary in LIFE noted that “he regarded the war between Nigeria and secessionist Biafra as his own.”

For his part, Okigbo, who had studied classics in university and once taught Latin, decided on a course of action that seemed uncharacteristically anti-intellectual. The best use of his genius wouldn’t be to serve Biafra as a roving ambassador like Achebe, or to work creatively, composing poems or anthems, or designing propaganda posters as the artist Uche Okeke did. In those desperate days, options were limited and the utopian claims of the Biafran Republic seemed non-negotiable—at least for those with an idealistic sense of duty like Okigbo. He joined the Biafran Army as a field-commissioned major, something he had gone to great lengths to keep from his family and friends, including Achebe.

“That’s my work, duty calls, so I must go there,” Ramrakha said, according to his brother, when asked why he went to places like Aden. Okigbo must have had a similar sentiment.

*

I wondered about the relationship between the two men and their era when I noticed similarities in a pair of poems. The first is a stanza from Osip Mandelstam’s poem “The Century”:

My century, my beast, who will manage

to look inside your eyes

and weld together with his own blood

the vertebrae of two centuries.

In 1971, Okigbo’s posthumous collection, Labyrinths with Path of Thunder, was first published, and included the poem, “Elegy of the Wind,” in which he wrote:

White light, receive me your sojourner; O Milky Way,

let me clasp you to my waist;

And may my muted tones of twilight

Break your iron gate, the burden of several centuries,

into twin tremulous cotyledons…

One poet wonders about the welding together of two centuries. The other hopes that the burden of several centuries might be broken apart. Okigbo’s conversation with Mandelstam, as I see it, is not necessarily about how their centuries might be approached. They are conversing, instead, about the ways an individual life fits within a span of time: a person can “look inside” the eyes of two centuries much as his “muted tones of twilight” can break its iron gate.

Read the full essay on The New York Review of Books.

_______________________________________________________________________

Otosirieze June 03, 2019 04:31

Hello Obinna. I did forget. I've included it now. I think the novel is overshadowed by Ekwensi's other books. Thank you for this observation.