1.

Writing this, now, at this temporal moment, means that I am not finalizing my application for a fellowship I’m applying to whose deadline is today. This is one of the things: that I’m applying for a fellowship, at the urging of YAO, and BK, who, some time last year told me to look outwards, to a country where there is a literary structure. Elsewhere, BK, speaking with ___, will say, “I did not tell him that he clearly needed a break from more practical mediocre types in his set who were making him think he was a genius. A lot of the most brilliant young writers on the continent are so comfortable in their own spaces that they are scared of going into the real test of a bigger scene that doesn’t give a fuck.” This is another thing: that BK thinks that there is no literary structure in Kenya (Africa), that very little works here, that thinking of the abroad is the way.

I have been thinking about the literary novel. I have maintained, in conversations with other Kenyan literary hustlers, that in the five-year span between YAO’s two books, only one literary novel by a Kenyan writer has been published, and I have been wondering what this means, whether it means anything. The literary hustler, viz., a writer, usually in their (early) twenties, but not always, trying to define themselves as a writer before the perils of responsibility make such definitions impossibilities (but not always). An addendum to this is asking myself why the literary novel, why not the nightmares of commercialism that are published in the country (still novels, to wit), why I choose to consider only Peter Kimani’s book. Or, as put elsewhere, by the Great White Male American Novelist of our time (henceforth referred to as GWMAN1)—the one who became the Great White Male American Novelist of our time mostly because of the death of his best friend, the hitherto Great White Male American Novelist of our time (henceforth referred to as GWMAN2, or, one other time after his)—“Why bother?”

[This is a version of the essay I promised _____ ten months ago but never delivered.]

What is the literary novel, and why am I writing one? David Wallace, age forty, SS no. 975-04-2012, the eponymous narrator of The Pale King, the posthumously published last novel of GWMAN2, observes that “. . . you will regard features like shifting p.o.v.’s, structural fragmentations, willed incongruities, & c. . . .”

[This is somewhat taken out of context to enable me to make my point.]

So, the literary novel, viz., that with such features as shifting p.o.v.’s, structural fragmentations, willed incongruities, etc., etc. (James Wood, of course, derides this type of writing, arguing that, “The big contemporary novel is a perpetual-motion machine that appears to have been embarrassed into velocity. It seems to want to abolish stillness, as if ashamed of silence—as it were, a criminal running endless charity marathons. Stories and sub-stories sprout on every page, as these novels continually flourish their glamorous congestion.”) I texted YAO, and asked her why she writes, why she writes literary fiction. For her, it is less the literary fictioning, the willed incongruities & c., and more the writing, more the storytelling, in whatever form it occurs. Even music lyrics. But Mimi, a date, asks me what kind of writing I produce, and I tell her that it’s “literary writing.” A decision I’m making early is that I can only do literary writing, and that the only other forms that would attract me have barriers that seem, at this point in time, insurmountable. Music lyrics a la YAO, for one, would be pointless, because, with music, the point is less the lyrics, less the story, less the concept, more the direct emotionalization (Ayn Rand, The Romantist Manifesto, which is, coincidentally, the only thing by Rand I would quote). And film (or that form that used to be called “movies,” a waste of time, before it was intellectualized into “film,” a noble pursuit) confers too much attention on the non-writers for my arrogant, egotistical self to consider it as a profession.

2.

In June 1962, in Uganda, a group of African writers and poets and thinkers and academics gathered at Makerere University to try and define for themselves how literary production would happen on the newly-decolonized continent. Years after the conference, literary production would oscillate around certain centers: at Makerere, at the University of Ibadan, at the University of Nairobi. Thus, the Nairobi Revolution became a group project. The Nairobi Revolution: a cultural uprising led by a group of young writers and academics at the University of Nairobi protesting the teaching of English Literature at the university over other (African) literatures. In her plenary lecture at the University of Nairobi as part of Kwani?’s 10th anniversary celebrations, the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie would confess herself to be “a hopelessly sentimental pan-African,” and—finding a connection between the Makerere Generation and the Kwani? Generation—say that the Makerere Generation had come together “to acknowledge and affirm each other.” Yet, as the Nigerian thinker Obi Wali pointed out in the aftermath of the conference, the Makerere group was by nature exclusive, interested only in writers who wrote in English, and even then only in those who wrote from the Universities of Nairobi, Ibadan, and Makerere.

This exclusive property of the Conference would come to affirm itself at the University of Nairobi years later. In the wake of the Nairobi Revolution, a certain coterie of academics had established their credentials as radical reformers in the Department of Literature. Down with English Literature!, this group of youthful thinkers had declared, and down went English Literature, and in came the Literature of the Africans. (Apollo Amoko’s Postcolonialism in the Wake of the Nairobi Revolution: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the Idea of African Revolution, the definitive text on this, has an acacia tree on the cover, and is published, of course, in the West, a point I will come back to again and again.) The Africans had won! We would teach ourselves! Down with the canon of Milton, Shakespeare, Yeats and all the Brits, and in with our canon. Acknowledging and affirming ourselves. And what would we teach? Our work, of course.

This is how a culture is born. Social revolution in groups. Jesus Christ, yes, but also, Jesus Christ and The Twelve Disciples. A group oscillating around a central figure, but still a group nonetheless. Berry Gordy at the centre of Motown, but also Motown existing in itself as a part of Afro-American culture, as a revolution in music, as a distinct genre of music. James Ngũgĩ and Taban Lo Liyong and Henry Owuor-Anyumba at the centre of the Nairobi Revolution, but still, the Nairobi Revolution, not the Owuor-Anyumba Revolution nor the Liyong Revolution nor the Ngũgĩ Revolution. Otis Williams at the centre, but still The Temptations, with five distinct voices.

Years later, at the University of Nairobi, I would hear whispers about the voices that had been considered worthy of acknowledgement and affirmation. Just as Obi Wali had warned earlier, the Academy looked to itself, and the Great Kenyan Novelist became Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, and voices not in the Academy were shunted sideways, ignored. In the same whispers, I would hear that the clique around Ngũgĩ had specifically made sure that Meja Mwangi would not be taught at the University. (For the uninitiated, Meja Mwangi is the chronicler of Nairobi, especially with Going Down River Road [1963, 1976] and The Cockroach Dance [1979].) The pantheon of Kenyan writing has space for only one individual at the top, and this individual must be in the Academy (Obi Wali scratches out his eyes in his grave), male and Gikuyu. (The fact that Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor is in neither of these last two demographic groups makes the Academy resist her inclusion into this pantheon.)

Half a century after the Nairobi Revolution, in Nairobi, Kwani? was born. Kwani?: a group concerned with literary production, but also a collective of different individuals concerned with their own individual cultural careers. The Reddykullas Generation. 2002 meshing into ‘03, and Kenyans had been declared, by a Gallup poll, the most optimistic people in the world. Yote yawezekana bila Moi! Parselelo Kantai, writing about this Reddykullas Generation, a generation whose central experience was survival, would declare that “a new Kenya was developing from the margins,” that the project of renewal was being replicated everywhere, that Kwani? had sparked a literary renaissance in the country. Binya had just come back, Caine Prize in tow, and a literary culture was being established. Exciting times were nigh. The Kenyans were writing again, writing in visibility, emboldened by the optimism of the end of the Moi regime. Binya had won the Caine Prize, and Voni would win it the next year, and Parsa would be on the shortlist the year after Voni’s win, denied a win only by, depending on who you believe, literary geopolitics that meant that Kenyans couldn’t win the prize three years in a row. The Reddykullas Generation was doing it. The thing was being done.

Sometime early in 2019, Parselelo and I would talk. Shoot the breeze. Catch up. Touch base. Whatever the nomenclature. A new project was being set up, and since the two of us were the only ones of the team in Nairobi, it made sense for us kuongea vitu moja mbili tatu. And we talked our one two three things. Writing. Wolfe & Thompson & the New Journalists. Football. Hockey. Sports. Vitu Vingine. Etc., etc. Near the end of our conversation, I asked him about his novel, about Binyavanga’s novel, about the Reddykullas Generation’s novels. In the haze of the Nairobi dusk, Parselelo looked me in the eye and took a drag of his cigarette. “My novel,” he said, “that I never finished is my biggest regret.”

3.

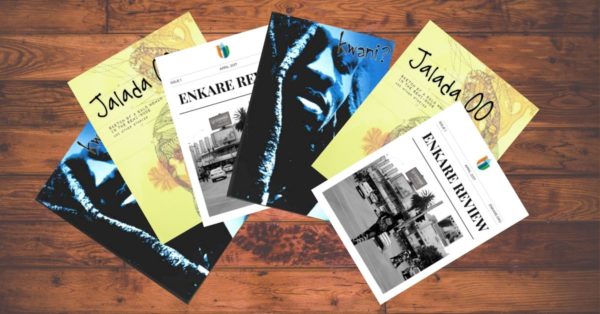

At a party in 2017, someone asked if Kwani? and Jalada Africa and Enkare Review were connected. Kate Wallis has written about the relationship between Farafina and Kwani?, and about how this relationship proved beneficial to writers around both spaces. Wallis writes:

Out of these brief and partial snapshots of the literary prizes and institutions represented by significant figures in the launch of both Fine Boys and Dust, it is possible to begin characterizing the literary network out of which these novels are produced. They reveal a literary network that is Pan-African yet intimately connected to significant institutions within Kenya and Nigeria, as well as significant institutions in New York and London; a network that is rooted in the histories of Farafina and Kwani Trust but that out of which, and alongside, new significant literary publishers and initiatives have materialized over the last decade — from JALAA to Jalada, from Storymoja to Parresia.

It isn’t necessarily the same with Kenyan literary spaces. These connections are harder to spot. Of course, Jalada sprouted from the sidelines of a workshop organized partly by Kwani?, but there is little else binding the different LINGOs. Instead, a pattern. Dorothy Strauhs: “First and foremost, a LINGO is a nongovernmental organization with a focus on the production and promotion of literary talent, events, and publications that is situated in the nonprofit sector.” Thirty years after the Nairobi Revolution, Kwani? in 2003. After Kwani?, Jalada Africa in 2013. After Jalada Africa, Enkare Review in 2016. And all the new significant literary publishers and initiatives. A steady chain of literary journal/writer collective hybrids undertaking in the tasks of literary production, in the experiments of learning and unlearning and relearning, moving in form to adapt to what they/it needs to accomplish. Sawa. But then, what is the elementary code of the literary unit? What is the element literary unit? In the West, one is able to observe how things work, how cultural units work, how cultural units ought to work, how the system make them work. In the Nairobi/Kenyan/African cultural scene, one gains the knowledge that these systems do not exist, that the literary unit can never settle, because there is no optimum environment in which to settle. We are like the Cushitic pastoralists in the deserts of Northern Kenya who move with their cattle across the terrain, in search for pasture and water, a continuous walk that never ends, never stops. Don’t stop, don’t settle. The mutation goes on all year long, year after year.

Skiza, this was how Enkare Review worked. I was having a conversation with someone who was also part of the formation of ER (and who also shares all the founder capital this supposedly brings), and she said that in a few years, a new group of kids will come up and decide that the lit scene in Kenya does not work, and gatekeepers be gatekeeping and that we need new names, and they will start something new. That was us in 2016. Still, from the start, the thought in my head was that I was going to be part of this new African LINGO for a set period of time, and then I would move on to other things.

We were going to crush the entire gatekeeping process. Ha! Now, I am less willing to see the value of such gatekeeping-crushing endeavours. Or, now, I am thinking of other things, things like the writing of the literary novel, things infinitely more important than running the LINGO. In conversations with both Billy Kahora and Moses Kilolo, former managing editors of Kwani? and Jalada Africa respectively, the preeminent Kenyan LINGOs, both expressed to me their constant regret at having spent copious amounts of their energies building up these two institutions at the expense of their own writing careers. From other voices I will hear complaints about BK and MK’s helms at these LINGOs, but from them, the resolute declaration of their disappointments.

A. Igoni Barrett questions why he persisted in being a publisher, in running a publishing company rather than doing the writing that had driven him to abandon his agriculture degree at the University of Ibadan (one of the original Centres). He quit, started writing in the West (while still managing to live in Nigeria), and found, to his satisfaction, that “The sole task entrusted to me was the only one I wanted, which was to write whatever I wanted.”

And so, because I am thinking about, and other things pia, I quit ER. December 2018.

4.

A few weeks later, I am with W., a former Kenyan literary hustler (former to mean that she had given up on a career in writing, and was now hurtling fast into academia), on our way to Maasai Mbili, a gallery in Nairobi. W. mentions that she worries that I have too idealized an idea of the kind of writer I wanted to be, that she doesn’t know if I will able to handle failing at my dream. Earlier in the year, a friend and I, a fellow Kenyan literary hustler, had acquired a joint subscription to The Paris Review. For months, I read TPR interviews, trying to shape my thinking around the writing process. McPhee. Toni M. Didion. Franzen. I read them, all the Americans’ opinions on the art of fiction/nonfiction/the essay/journalism/ & c. & c. G., a fellow literary hustler, asks me why I am so obsessed with them, these Americans. An unnecessary question, I think, in my head. (The old argument by Naipaul, that the colonial is obsessed with the colonial master, springs to my mind now, and the US of A is the cultural colonizer of our time.)

In a few months, W. will start her PhD. She tells me this, and I confess to myself that her literary writing is going to be nothing more than sporadic. W. is a version of myself that I could become, the version of myself I always assumed that I would become. But now, instead of becoming a proper academic, instead of applying to the MA and MPhil programs I had assumed de rigueur, I am thinking of MFA programs in the West. Elif Batuman, writing in The London Review of Books, questions the utility of a degree in creative writing. Get a real degree, she declares. The programme era, she says, she is not a fan of, and that if she wanted to read literature from the developing world, she would go ahead and read literature from the developing world. Furthermore, Mark McGurl, whose book, The Programme Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing, Batuman is writing a rather enjoyable review of, posits how and why programme fiction has led to largely white writers asserting the privilege of other narration, while minority writers have typically been asked to slot themselves into a single ethos. Batuman writes:

The law of ‘find your voice’ and ‘write what you know’ originates in a phenomenon perhaps most clearly documented by the blog and book Stuff White People Like: the loss of cultural capital associated with whiteness, and the attempts of White People to compensate for this loss by displaying knowledge of non-white cultures.

Still, the MFA program in creative writing. And literary writing. And the Novel. Literary writing is an inherently elitist profession that seems, to me, to serve no other function than emboldening the writer’s narcissisms. For Batuman, “Literary writing is inherently elitist and impractical. It doesn’t directly cure disease, combat injustice, or make enough money, usually, to support philanthropic aims.” GWMAN1’s struggles with this was at the heart of his 1996 Harper’s essay. He had envisioned his first novel, The Twenty Seventh City, a book about his hometown, St. Louis, as the book that would evoke conversation in the public domain about immigration, and about the decline of American cities. Instead, it, and his second book, Strong Motion, were, while praised by critics in and around the academy, roundly ignored by the general public. As his writing continued to make barely a ripple in the populace whose attention he craved, GWMAN1 started to despair. Why bother?, he asked:

At the heart of my despair about the novel had been a conflict between a feeling that I should Address the Culture and Bring News to the Mainstream, and my desire to write about the things closest to me, to lose myself in the characters and locales I loved. Writing, and reading too, had become a grim duty, and considering the poor pay, there is seriously no point in doing either if you are not having fun.

Critics of Kwani? and Jalada Africa have argued that there was a hegemonic point behind doing the LINGOs. On social media, and in other spaces, dissenting voices have argued that the elitism of these LINGOs excludes outsiders from the privileges manifest in these spaces, an argument that is, to some extent, not entirely untrue. One of these privileges was money. The donors. Writing in Blind Field about what she calls “the African Literary Hustle,” Sarah Brouillette notes: “The field of contemporary Anglophone African literature relies instead on private donors, mainly but not exclusively American, supporting a transnational coterie of editors, writers, prize judges, event organizers, and workshop instructors.” This, of course, is nothing new. Ayei Kwei Armah famously dismissed the African Writers Series as “a neocolonial writers’ coffle owned by Europeans but slyly misnamed ‘African.’” Brouillette continues: “There is donor funding to support the activity of writing, to award prizes to authors, and to facilitate access to US and other foreign markets.”

These foreign markets are the targets of many writers on the continent. Is the goal, in the end, to write for the foreign markets? Whom do we write for? Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, writing in The New York Times (ha!), thinks so, arguing that:

But we are telling only the stories that foreigners allow us to tell. Publishers in New York and London decide which of us to offer contracts, which of our stories to present to the world. American and British judges decide which of us to award accolades, and subsequent sales and fame.

In his response to Nwaubani’s piece, A. Igoni Barrett was categorical about why he decided to write in the West:

What worried me was my future as a writer in Nigeria. It I had learnt anything since 2005, it was that it was impractical for any investor to turn a profit from selling literary fiction in a market as difficult as Nigeria. All those hardscrabble years spent as a local talent had confirmed to me that success for most writers in English—whether African or Australasian or Asian—depends on the publishing powerhouses in the West, mainly in New York and London.

And so the MFA, and the admission into the centres of publishing in New York and London that we (I) imagine it will grant us (me).

I hear news of people who would be considered my contemporaries being admitted into these programs, into Iowa, into East Anglia, into Brown, and smite my teeth in chagrin. When I was eighteen, I decided that I would not study in the West, that I would not study in the West because to me it’d reek of rank betrayal. I was enamoured by the idea of the University of Ibadan, but more so by the University of Nairobi because of Ngũgĩ and the ideas of the Nairobi Revolution. I wanted to exist in the same corridors as these stalwarts of what was to me “authentic African literature.” There were certain people around me, people who were either my friends or people with whom I shared brief romantic affiliations, and they had studied or were studying English in the abroad, and I sneered at the idea of anyone studying the Literatures of the West, the Literatures of the Colonial Oppressor. The Nairobi Revolution, didn’t they know?

But this is a part of me that is long gone, nothing more than an aberration. Now, I will do such things as express to a person the inherent uselessness of any sort of literary endeavour in Kenya (starting a lit mag is a useless bone-crushing enterprise). Now, I will do such things as, like the elitist I have become, declare that only one novel has been published by a Kenyan in the years between YAO’s two, a not very good one at that. Now, I understand the desire for the West.

5.

In the second half of 2018, Otieno Owino and I decided to start a publishing company. (The Kenyan literary hustle.) Over several days, we met and talked, came up with a publishing plan, declared to ourselves that we were going to save the Kenyan literary publishing scene. We drew business models, considered revenue streams other than from book sales, and vowed to eschew donor funding. YAO’s book was due out early in 2019, and the aim, for me, was to secure the local rights. Kwani? seemed to be easing its way out of the scene, as had been exemplified by an editor’s tweets about their nonpayment of staff salaries for months on end. So, YAO’s book. And others after. We knew which Kenyan writers were writing novels, and wanted to publish them all. Somewhere in my house this list exists, the Kenyan writers we would approach, and the year-by-year timeline in which we would publish their books.

In time, however, the old doubts began to creep in. Igoni questions why he had to be a publisher, an editor, a PR person, a manager, all sorts of things that were not what he wanted to do, which was to write. At ER, months before whatever storms would be kicked up on social media, I had begun to question the utility of what I was doing. I had broad curatorial control over everything that was published on the website, and even as I exchanged emails and edited and interviewed these writers of a certain importance, writers who had won the important prizes, I sensed a growing resentment about what I was doing. In the months surrounding the furore on social media that followed the hacking of ER’s website, when I had mentally checked out of everything ER, some of these writers of a certain importance would email and call and DM me on social media, and say things about how we had to keep on doing what we had been doing, that our work was important. Later, after I quit, I would bump into one of the writers, and he would accuse us of having killed ER.

I have to desire a certain literary structure around me. Where, if one wanted to get their fiction or poetry or nonfiction or whatever published, they wouldn’t have to perform the drudgery of starting their own platform. The publisher Otieno and I were starting, we named it Kafira Press, after the country in Francis Imbuga’s Man of Kafira and Betrayal in the City. There are certain people, agents and money people and whoever, who know me solely as one of the front figures of Kafira Press. Still, all I wanted to do was to finish my novel and have it published, and here I was, caught in the same noxious circle, trying to build the entire structure from the ground up. Madness, if nothing else.

Anyway, Kwani?. Literary observers across the continent question why there are precious few literary novels by Kenyans. Maybe the answer lies in the fact that beyond Kwani?, Kenya has not had a publisher willing to put out literary work. Maybe the answer lies in the fact that Kwani? itself published zero books by Kenyan writers. Even BK’s book, despite his being the long-time Kwani? editor, is not published by Kwani?. All these structures, despite people’s best attempts, that have not worked. Binyavanga died, and a thing I can’t get past is that he never published a novel. (The Literary Novel, remember?) I asked Parselelo whether it mattered, that he and Binya and the rest of the Kwani crowd, The Reddykullas Generation, that would spark literary renaissance in the country, had, with the exception of YAO, not published novels. (Of course it mattered.) I look at Jalada, the literary collective that promised much, and think about the fact that all these years later none of them have novels. (Clifton Gachagua does have a full-length poetry collection, but that was pre-Jalada.) Perhaps these things don’t matter as much as I think they do, but even if they do, why bother?

Still, the Kenyan Literary Hustle continues.

Frankline Sunday, a Kenyan journalist whose MA thesis is on the vagaries of online literary publishing, launched a literary journal, the potential for incestousness in such a move notwithstanding (Full disclosure: I have work in said journal). I hear of other such attempts, other groups of people attempting such ventures. The hustle doesn’t stop, can’t stop, but my patience wanes, and I take BK’s words in stride, his words about moving somewhere the literary structure exists, where it doesn’t need to be built anew.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Carey Baraka is a Kenyan writer. He sings for a secret choir in Nairobi.

Making Peace with Our Past: A Dialogue with Hamza Koudri – Africa in Dialogue September 29, 2022 04:26

[…] Carey Baraka, who co-founded the Enkare Review, highlighted a few downsides of running a literary […]