During a June 2019 Heinrich Böll Stiftung memorial event in Berlin, the novelist Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor delivered a moving tribute to Binyavanga Wainaina, who died in Nairobi on 21 May 2019, aged 48. Owuor, whose Binyavanga-edited and Kwani?-published short story “Weight of Whispers” won the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2003—the year after Binyavanga’s own win—wondered aloud whom she would send her drafts to, now that the person who pushed her hard and gave her writing no-holds-barred critiques was no more.

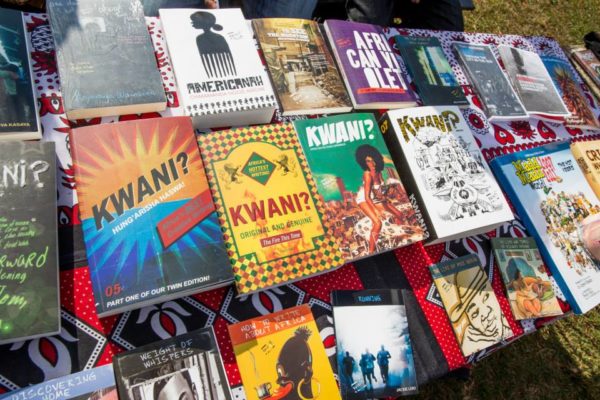

Kwani?, with Binyavanga as founding editor, burst into the literary scene in2003, ushering in what the writer and journalist Parselelo Kantai—who was shortlisted for the Caine Prize in 2004, after Owuor, and who together with Owuor were among Kwani?’s founding inner circle—likes to call “The Age of Love.” To Kantai, a literary revolution had befallen them. There was a wave of fearlessness and promise permeating in their midst, to the point of driving some to quit their jobs and spend entire afternoons which ran into late nights drinking, eating, and talking. Kenyan strongman Daniel arap Moi had finally left power after 24 years, a period aptly summarized by one of Moi’s more eloquent critics, Michael Kijana Wamalwa, who proclaimed that “The Moi era was a great error.” With Moi’s exit, Kenyans were polled as the most optimistic people in the world. This newness played into the Kwani? moment. It was time for a national reboot, and literary aspirants would not be left behind.

According to Kantai, Binyavanga had the requisite pulling power and an inexhaustible energy reservoir to keep the group and ideas going, despite the chaos of his own disorganization. Pushing everyone to write and send in drafts, the journal was born, its name the Kiswahili for “So what?” A lot of those pre-Kwani? meetings happened at the home of the recently deceased inimitable editor Ali Nadim Zaidi. Apart from playing host, Zaidi, who has been described by the Ugandan writer A.K. Kaiza as “that éminence grise that all newspapers must have—that one in-house intellectual and grammarian commanding a battery of section editors,” and praised by the veteran Kenyan journalist Philip Ochieng (as reported by Mwangi Githahu) as “the most imaginative East African headline writer (in English),” seemed to be the group’s ideological North, that one older guy whom everyone could consult about anything and everything.

Apart from Zaidi, the other hosts were the writer and journalist Rasna Warah whose apartment block’s pool side was a favourite, the fashion designer Anne McCreath who prepared feasts for the group, the human rights activist Muthoni Wanyeki who housed Binyavanga at the time, and Professor Wambui Mwangi who is credited with giving the group some much-needed intellectual fire power. As things took proper shape, McCreath and Wanyeki became members of Kwani?’s inaugural board of trustees. However, they both quit after some time, giving credence to whispers that a distance had developed between Kwani? and some of its founders, who no longer held sway as originally imagined. Thereafter, other than Binyavanga—who later moved on to other roles such as the directorship of the Chinua Achebe Center at Bard College—the Kwani? board was populated not only by non-founders but also by individuals who were not involved in the literary or creative sectors.

According to those in the know, Prof. Mwangi arrived in Nairobi from her Canadian base and turned things upside down, asking anyone and everyone she came across to apply for that fellowship, to quit their unfulfilling corporate gig and enroll for that graduate degree, to not be mediocre and settle for the less that Nairobi was offering. From holding Binyavanga’s hand and lining everyone around up for the great literary takeover, the role played by Prof. Mwangi cannot be gainsaid. However, it was Zaidi’s home that became the unofficial headquarters for the group, as recollected by Zaidi’s eldest son Franco at a recent cookout in remembrance of his late father held at Corner Baridi in the outskirts of Nairobi. Asked by Kantai how much of the family fortune must have gone into buying firewood for the late night bonfires, Franco reminisced about raiding neighbourhood hedges looking for dried wood. The fires were his to keep burning. He had to find a way of doing this without breaking the bank. “I was always on the lookout for trimmed hedges,” Franco said. “I was always at hand to pick up dried-up twigs or pull down dried-up tree branches and bring them over. I had a stockpile.”

It is therefore no coincidence that whenever the Kwani? tale is told, Zaidi’s and Binyavanga’s names feature prominently—Zaidi for playing host and Binyavanga for using his 2002 Caine Prize-winning money to give the Kwani? founding group fresh impetus. But as much as they had a myriad similarities—the big physiques and the accompanying big hearts, their eternal pleasure to mentor, their love for rigor and inquiry, the open door policy to both their homes characterized by epic parties and the attendant heavy drinking and smoking—Binyavanga and Zaidi personified how two individuals could be so alike and yet so different. Zaidi was a dyed-in-the-wool ideologue, an unapologetic Marxist, while Binyavanga’s were a most fluid politics, forever oscillating like a disturbed pendulum between contradicting standpoints. These ideological gaps notwithstanding, Zaidi, Wambui, Binyavanga and others ably midwived the Kwani? zeitgeist.

However, at the July 2019 event in Berlin where Owuor delivered the somber keynote, something which has been whispered about for a time was spoken about publicly for the first time. During the conversation after her presentation, which discussion featured the trajectory of Binyavanga’s life, Owuor was asked about the state of Kwani?, which was rumoured to be on its deathbed. Was there a nicer way of telling the truth, or would she say it like it is? “From what I know,” Owuor said, “it seems like Kwani? itself has followed the life of its founding spirit. I think it’s in the ICU right now, but I’m sure it will return after a season.”

Kwani?, that once forceful publication which captured a generation’s imagination and desire for a different conception of Kenya and the world, had shockingly found itself in a near-death situation. How such had happened or been let to happen when at its founding it had some of the most benevolent and accomplished individuals rooting for it still beats the imagination. But with time, hypotheses of what might have led to Kwani?’s decline started emerging.

RESPONDING TO A Twitter conversation on how Kenya has a thankless culture of betraying its whistleblowers, the Kenyan academic Dr. Wandia Njoya wrote, And Munyakei’s story was published by Kwani?, the innovative literary forum that I hear was infiltrated and collapsed by the state. Dr. Njoya’s words marked the first public articulation of the state infiltration theory, which had been quietly doing the rounds within the Kenyan literati and civil society circles.

A beneficiary of generous donor support (Ford Foundation’s figures alone are $255,500 in 2007, $395,000 in 2008, $600,000 in 2010, $130,000 in 2013, $50,000 in 2014, and $150,000 in 2015), Kwani? was poised to underwrite extensive literary works, freewheeling in its choice of subject matter, and so it was that it found David Sadera Munyakei, the whistleblower whose story it told. A junior clerk at the Central Bank of Kenya who spilt the beans on Kenya’s biggest heist of the 1990s, Munyakei was out of work. With nowhere to turn to, he died a pauper at Olekurto village. Before his death, Kwani?’s Billy Kahora tracked him down and wrote a biography, The True Story of David Munyakei (2008), detailing Munyakei’s travails, the struggles of his young family, and his eventual relocation to the village, where death struck.

How had Kwani? gone from doing national duty by preserving Munyakei’s story to being suspected as a somewhat willing victim of state infiltration? Oh! Is that what really happened to Kwani?, someone asked. I’m told it is, Dr. Njoya replied. By good sources. When Kwani? showed up, the state commissioned people to undermine it. Someone who worked at Kwani? until the curtains fell, and as General Manager no less, was keen to corroborate Dr. Njoya’s assertions on the thread. I worked for Kwani? and learned about this as I was about to leave, the former GM wrote. I couldn’t believe it at the time, but in retrospect (hindsight is 20/20) it all made sense.

Earlier on in May 2019, when Binyavanga passed on, Dr. Njoya had tweeted: Binyavanga liberated our art from the literature police in Kenyan universities. As the infiltration thread further unfolded, Dr. Njoya seemed to reiterate her May sentiments. Binyavanga’s work and life stirred a hornet’s nest. I wonder whether he was aware. My one regret is that I didn’t understand it while he was alive. I would have asked him if he knew what he had done.

What was it that Binyavanga had done, and who/what was the hornet whose nest he stirred?

Many will agree that Kwani? was not a political-revolutionary project seeking to weaken or overthrow the Kenyan state. Compared to what Ngugi wa Thiongo’s contemporaries did in the ’70s and ’80s at the University of Nairobi—Marxist intellectuals and ideologues intent on upsetting the political status quo by use of whatever tools at their disposal: language, theatre, lectures—Kwani? does come across as revolution-lite. Of course Kwani? had its cultural revolutionary-ness, which seeps into the political. But the difference between Kwani? and what the subversives of the ’70s and ’80s were engaged in is that the latter cohort was first politically sold to the cause of dismantling the authoritarian state, with those involved being some shade of the left—socialists, Marxists, communists, Marxist-Leninists, Maoists, maybe even Trotskyites. Kwani? was therefore a vehicle for an artistic revolt, but beyond language, posturing and aesthetics, what were Kwani?’s intentional and threatening politics?

“A lot of times things are set up to knock on the state’s door,” Kantai recently told me over beer in Nairobi. “The desired result is that either the state will open its door and let you in, or someone from outside who is opposed to the state will open their door to you, so that you face the state together. To my mind, Kwani? wasn’t set up for either of these purposes. It was independent of this sort of thinking, and was simply an open space for imagination.” According to Kantai, it is this space-for-imagination philosophy which led most of them into writing fiction, because it was a new reality to journalists like himself, a chance to inhabit a different world of creativity even if they wrote about their everyday experiences. How this became a threat to the state—artists minding their business, finding their voices, not focusing on upsetting the political status quo per se—remains a subject for broad speculation.

I suspect GoK (Government of Kenya) is shutting doors on artists, Dr. Njoya opined on the infiltration thread. The only ones who get international government support are the ones who don’t go to the grassroots or challenge the status quo. And I don’t even mean political challenge. Anything that nurtures imagination is a challenge to the state. The implication of the above statement could be that Kwani? was stifled of funds from outside Kenya because of its imagination project, which, according to Dr. Njoya, was a threat to the state. The question one may want to ask then is, how is it that the state used those inside Kwani?— the alleged infiltrators—to ostensibly sabotage the organization’s overseas money channels?

As the infiltration rumours gained traction over the years, one individual’s sins of commission and omission seemed to further fuel it as well as heavily haunt Kwani?. Few founders have the sort of effect Binyavanga’s shadow, ideas and chaos had on Kwani?. As a result, even after leaving Kwani?, Binyavanga and Kwani? were considered synonymous, and whatever Binyavanga did reflected on Kwani? and vice versa. There are those who posit that as much as Binyavanga himself was not singled out as one of those within Kwani? alleged to be working for the state, some of his actions after he left the organization seemed to support the suspicion. In his last days, Binyavanga made a deliberate effort to reverse some of these actions, by which time Kwani? was no longer a going concern. The chips had already fallen wherever they had.

Binyavanga’s mantra was “Don’t wait for permission. If you see space, occupy it.” His was a confidence-building project. However, what really were Binyavanga’s politics: could he have deliberately or mistakenly created room for the infiltration, for instance, and did he transmit them to Kwani?? Out of the tens of conversations we had at Kantai’s backyard, where Binyavanga and I found ourselves most drinking nights, the thing one took away was that the ball of energy and ideas that was Binyavanga didn’t have a solidly formed politics away from his socialist tendencies. His was an eternal search for a political home, a pursuit for a set of beliefs that would offer a huge enough tent for him and his wondering and wandering mind. Even what he became a champion for later, standing up for sexual minorities, had simmered within him for a long time before manifesting, understandably so. These could not have been easy burdens for anyone to carry.

As we swam through this turbulence powered by Tuskers and an early morning whiskey, Kantai always revisited their conversations with Zaidi, who had always urged Binyavanga “to read Marx.” Kantai’s act of circling back to Zaidi seemed to not only exemplify Zaidi’s centrality to the coming to life of Kwani?, but his hope of ideologically tampering with the hearts and minds of the emerging vanguards of the literary revolution that it represented.

According to A.K. Kaiza, whom Zaidi also urged “to read Marx,” Zaidi wasn’t forcing his Marxism on anybody, but must have thought the Kaizas and Binyavangas could do with some grounding. As if reading Zaidi’s mind posthumously, the writer and researcher Dr. Paul Goldsmith, a friend of Kwani? and Zaidi’s, recommended to millennials in his reflections on Zaidi, titled The Man Who Brought Marxism Back to Kenya, that “…a dose of Ali Zaidi-style political theory might help them fill the gap in their existential critiques.” It seems that even in death, Zaidi is still telling everyone to “read Marx.” Did the Kwani? founding crew read Marx, and if they did or didn’t, what was the long term effect of their commission or omission?

Binyavanga, I can report, did not “read Marx,” and he never hid it. One morning over breakfast a few years ago, Binyavanga suddenly wanted to become a socialist, and came at me with all kinds of questions. Did he need to read Marx, he wondered. This was vintage Binyavanga, never afraid of asking the most basic questions about anything. For those who knew him closely, it was inescapable to notice that in Binyavanga’s brilliance lay an eternal curiosity, to want to know the little details about everything, which hunger for meaning or truth no one thing or set of things quenched satisfactorily. It could have been that loose-ness, that need to not be tied down to one set of beliefs, that could have made him not want to take a single path, to be a Marxist or whatever else anyone thought was good for him as a politics.

However, with time, Binyavanga’s contradictions started showing publicly.

IN 2013, BINYAVANGA wrote a piece titled “Kenyans Elected a President We Thought Could Bring Peace,” published in The Guardian. The op-ed, which endorsed the election of Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto—who were at the time facing crimes against humanity charges at the International Criminal Court (ICC)— immediately prompted loud murmurs. Not everyone was enthusiastic about the election of the two ICC suspects, and the chatter was, why had Binyavanga thought it necessary to take sides in a highly polarized political environment? Did he understand the full implication of that election, and would he live to regret his decision?

After that election and the publication of his Guardian piece, an activist friend of Binyavanga’s invited him over for a Christmas party, to which Binyavanga asked me to accompany him, since I had no plan. Sitting at the backyard of the activist’s home, with a number of prominent artists, journalists and an easy going European diplomat present, the conversation naturally veered towards the Kenyan cases at The Hague. Everyone present seemed to believe Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto shouldn’t have been allowed to stand for election in the first place, courtesy of their being guests of the court at The Hague. Before the conversation could go any further, Binyavanga, in a characteristic bold intervention, strongly expressed displeasure with the idea of Africans being tried in a foreign land, something which came out as a not-so-veiled unquestioning support for the ICC suspects. Everyone pulled back quietly, in apparent shock.

It seemed there had been an expectation that those invited to the party somewhat shared the “Kenyan liberal” view, which at the time meant supporting the prosecution’s cases at The Hague. How could Binyavanga, a celebrated Kenyan intellectual, be the one appearing to defend the two elected suspects? The camaraderie at the garden died a natural death, with everyone now trying to make unimpressive and unsustainable small talk, aware that not all those present believed in the same things as might have been earlier misconstrued. We left soon thereafter, with Binyavanga confessing that he sensed there had been a bigger conversation that was meant to happen there that afternoon, but that because of his views, that secret agenda had been shelved. He knew the implication of the shrapnel from his intellectual grenades.

Yet, for those who really knew him, Binyavanga was unafraid of being wrong, and if convinced at a given moment that one thing was his truth, he then defended it with his whole life. At that point in time, endorsing Kenyatta and castigating the court at The Hague made many conclude that he was pro-regime. That op-ed, written almost a decade after Binyavanga ceased running Kwani? but remained domiciled in its board of trustees, gave more life to the infiltration theory. Pundits questioned whether Binyavanga was doing someone else’s bidding, possibly someone in government, or if that were not the case, then was he siding with Kenyatta because they were both Kikuyu? Was Binyavanga complicit, or was he fumbling politically as usual?

Five years later, in 2017, after suffering a series of strokes and with a new sense of urgency, Binyavanga seemed to want to have a final word about his politics, especially with regard to his choice of publicly endorsing Uhuru Kenyatta in 2013. In one of his last writings, the piece, “A Letter To All Kenyans From Binyavanga Wainaina or Binyavanga wa Muigai,” published by Brittle Paper, read like a confession. Binyavanga admitted, among other things, that the 2013 election could have been rigged, going on to explain his conduct then, why he thought it prudent to endorse Uhuru Kenyatta. He was now declaring support for Kenyatta’s 2013 opponent, Raila Odinga, who was once again running against Kenyatta.

Reading the Brittle Paper piece, one sees Binyavanga’s struggles with politics and identity, the things a lot of his friends knew and saw even when he was at his best—his need to take a stand and still be comfortably himself. The playing around with his name, now calling himself “wa Muigai,” son of Muigai, as if to be his father’s son in the most complete way possible—as he had never deployed his father’s lesser known middle name before—showed his continued struggles with identity as a Kikuyu and as his father’s son, something he spoke about in the essay and elsewhere. Here was someone who was eternally searching, never resting.

However, it seemed the 2017 letter came in too late. It didn’t attract much scrutiny. The die, it appeared, had been cast through his 2013 op-ed. The damage, to him and Kwani?, was final.

BILLY KAHORA, WHO took over from Binyavanga, cannot be said to have had any detectable dangerous or anti-establishment politics. Having returned to Kenya after pursuing an undergraduate journalism degree in South Africa, followed by a stint as an editorial assistant for the news site AllAfrica.com in the US, Kahora was brought in by Binyavanga first as assistant editor in 2005. He eventually stepped into the head role in 2007, after Ebba Kalondo had briefly been managing editor. Much as Kahora spent more than triple the time Binyavanga did leading Kwani? editorially, he didn’t necessary set out to fill his predecessor’s shoes. There were primary issues of difference in personality—few can match Binyavanga’s largeness and largesse—but Kahora could be said to have spent more time looking inward than doing the sort of literary evangelism which was Binyavanga’s forte. There is agreement that Kahora and his executive director Angela Wachuka—whom Binyavanga similarly brought in around 2008 after her undergraduate studies in the UK and a stint with the BBC—spent a good chunk of time in their early days cleaning up the financial and organizational mess a laissez-faire Binyavanga had left behind, such that it took them time before they truly found their footing.

Some have argued that, editorially, Kahora was a reluctant leader, since all he wanted to do was write. On her part, Wachuka focused more on the managerial side of things, working to keep the editorial ship afloat. Yet when he got down to it, Kahora purposely applied his mind in making Kwani? a more pointed intellectual endeavor, more than Binyavanga had. Binyavanga was keen on both quantity and quality—get in more new writers, grow the circle socialist style—while Kahora was a quality person, out to ensure he only produced the best few. This laser focus and the generous amount of time he has spent at Kwani?—12 years now—allowed Kahora to oversee the publication of more than half of Kwani?’s total output. But is that Kahora’s complete legacy?

On the flip side, the salvos come in the form of accusations that “Kahora and Co.” closed Kwani? off and suffocated its sense of community, such that it became fully NGO-nised, no longer the fireplace where writers and intellectuals felt accommodated. As one writer who was present during Kwani?’s founding put it to me, “Billy turned Kwani? into a passport which he put in his back pocket, to enable him to travel the world.” A younger writer who sent in drafts which they suspect were never looked at opined that “Kwani? came to dismantle the university’s stranglehold, but it quickly became the new university, by restricting access.”

After Binyavanga’s Kwani? extravaganza—the big spending even with a minimal budget, the maximizing on publicity—it was Kahora and Co. who delt with the repercussions, and maybe in focusing on the technicalities in stabilizing Kwani?, the dreaminess was lost. Tellingly, one of Kahora’s common phrases, picked from our interactions whenever he commissioned me for work, was “What are the practical things we can start looking at?” Kahora was coldly practical, and maybe out of that, the big-bus-for-all that Binyavanga made of Kwani? was neither viable nor agreeable. However, the whispers about Kwani? being closed off, including to majority of those who participated in its founding, didn’t stop at the editorial level.

A number of individuals from Kwani?’s founding days contend that Binyavanga took what was a communal effort and ran away with it, populating its core with unilaterally selected friends and friends of friends, thereby turning Kwani? into a fortress for a few. Others blame him for leaving Kwani? too soon—he was off to the University of East Anglia less than three years after the founding, at a time when teething problems were still self-evident—and handing it over to his newly arrived proteges who might not have shared in the organisation’s original motivations.

The tenure of the leadership has also raised eyebrows. Some point out that the journalist Tom Maliti, picked as chairman of the Kwani? board of trustees at the organization’s inception, has continued holding onto the position to date, enjoying the power of appointing new board members whenever a vacancy arose while keeping Kwani? founders at bay. Kahora has led more than a decade as editor and Wachuka exactly a decade as executive director. Being the two central players, they were supported by a handful of hires, kept under ten at a time. This is closely followed by accusations that Kwani? was a Lenana School old boys’ crony project, seeing that Binyavanga, Kahora and Maliti all attended the school. Maliti was Binyavanga’s school captain while Binyavanga and Kahora shared a dormitory not too long after. Add to that accusations that Kwani? was either an elitist project courtesy of the class dynamics at play—the schools attended by those who led it and their socio-economic backgrounds—or part of a “Kikuyu hegemony” project, seeing as Binyavanga, Kahora, Wachuka and some others are Kikuyu. This last accusation, coupled with Binyavanga’s volcanic 2013 op-ed, became political gasoline.

These are the circumstances always revisited whenever the infiltration narrative is floated.

ACCORDING TO SOMEONE in the know, Kwani? became targeted by later-day detractors over allegations that individuals within it were leaking sensitive donor and other information collected from within the Kenyan civil society to proxies of hostile state agencies. A source who was present when the Kwani? matter was discussed at a high level donor meeting told me there was no way Kwani? could have survived the onslaught; those making the accusations were considered eminent persons within the East African civil society. Not ruling out foul play, there is a school of thought that places the allegations against Kwani? within the context of competition for the attention of financial benefactors. Others have gone as far as labelling it an elite Kikuyu power struggle, since those making the allegations and those being targeted within Kwani? and the state are all Kikuyu, a case of sibling rivalry fashioned as a moral contestation.

Others don’t believe the long stories. They put it squarely on the Ford Foundation, Kwani?’s longtime funder, for pulling out. But proponents of the infiltration theory maintain that covert state takeover is what informed donors leaving Kwani? out in the cold. There is also the aspect of a change of guard at the Ford Foundation, such that whoever took over might have been more inclined to believe the infiltration and other narratives, to Kwani?’s detriment.

It may be more basic than such chicanery. Others, including some who worked at Kwani?, blame extravagance at the top, a governance bankruptcy which saw the leadership pamper itself at Kwani?’s expense, and a lack of prioritization of The Writer—Kwani?’s primary concern.

Tellingly, a number of individuals within Kwani?’s founding group want to talk, but do not want to be quoted. To them, the truth is painful and divisive, such that they prefer to let sleeping dogs lie. Others do not ever want to speak about Kwani?. Could this be the reason why none of the Kwani? founders, some of whom are funders or associated with funders, wish to step forward and save the dying organization? One of them told me the literati space has always been infiltrated, going as far as giving me names of those known to be doing the state’s bidding.

As if that was not implicating enough, a writer who was following the infiltration leads told me he was warned by one of Kwani?’s founders to be ready to leave Kenya if he ever wrote the story, for his own safety. In even more hair-raising revelations, a set of younger writers confronted me with communication allegedly from individuals within Kwani? who had tried recruiting them for what was, for all intents and purposes, a state propaganda agency.

To others still, if anyone within Kwani? was a state agent, it wasn’t because they were there to gather any grand secrets about a plot against the state—because there wasn’t any. To them, the only sensible conclusion is that the state could have had fears of what Kwani? could have become—a space used to organize a more potent politics—such that the only way to abort a probable revolutionary politics from taking root was by having a stranglehold around the publication, so that an Ali Nadim Zaidi character, an avowed Marxist, wouldn’t take over it.

IN NOVEMBER 2017, as a cash-starved Kwani? was running on empty, with no money for salaries or utilities, a now conciliatory Binyavanga wrote to a group of Kwani?’s founding members, attempting to reverse the hand of time and redeem the organization. It was an attempt to reconvene the original vision-bearers, and possibly heal whatever rifts had gone unaddressed for nearly a decade and a half. If agreeable, then Kwani?’s founders could consider working towards a Kwani? 2.0. This was a surprise move, since Binyavanga had had a vicious social media fight with Kwani? over the remainder of what had been his medical fund. As he was going in and out of hospitals, revisiting and restoring Kwani? under the terms of its founding group seemed like the proper thing to do. Unfortunately, the effort didn’t fly. It might have been too late.

Whatever the cause of Kwani?’s stasis, one of Africa’s boldest literary experiments with a solid over 15-year run—17 years if you counted up to 2020—remains in the ICU with no office, no employees, no dependably functional website, nothing.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Isaac Otidi Amuke is a Kenyan writer and journalist.

One Day I Will Write About This Place, Binyavanga Wainaina | The Australian Legend September 26, 2024 16:46

[…] see also: The Struggle for Kwani?’s Soul, Isaac Otidi Amuke, Brittle Paper, March 12, 2020 […]