Stare up at the infinite stars through the port window of your hut and see the passage of eras. The light has travelled millions of years and you are directly looking at the past. You are unable to sleep despite the undlela zimhlophe the herbalist prescribed. It’s the dreams, the very lucid dreams, the herb induces that scare you the most — you’ve already seen so much in this world. Your eyes aren’t quite what they once were, but you see well enough to make out shadow and light, the pinpricks in the vast canvas that engulfs the world before sunrise. You are old now and don’t sleep much anymore. There will be plenty of time for that when they plant you in the soil where they buried your rukuvhute; right there under the roots of the msasa and mopani trees where those whose voices whisper in the wind lie patiently waiting. Your grandson Makamba messaged you yesterday and told you to look south to the heavens before dawn. This window faces east.

Your bladder calls out urgently so you grab your cane and waddle out, stepping round your sleeping mat and opening the door outside. Once you had to stoop to get under the thatch. Now, you’ve lost a bit of height and your bent back means you walk right under it with inches to spare. Your pelvis burns and you’re annoyed at the indignity of being rushed. It seems that time has even made your body, which has birthed eight children, impatient with you as you go round the back of the sleeping hut, lean against the wall, hitch up your skirts, spread your legs and lighten yourself there. The latrine is much too far away. The trickle runs between your calloused bare feet and steam rises.

“Maihwe zvangu,” you groan midway between relief and exertion.

When you are done, you tidy yourself, carefully step away from the wall, and patrol the compound. Each step is a monumental effort. It takes a while before your muscles fully wake and your joints stop complaining, but you know the drill now, how you must keep going before your body catches up. Young people talk slow when they address you, but they don’t know your mind’s still sharp — it’s just the rest of you that’s a bit worn out. That’s okay too; you remember what it was to be young once. Indeed you were only coming into your prime when the whole family was huddled around Grandfather’s wireless right there by the veranda of that two roomed house, the one with European windows and a corrugated zinc metal roof that was brand new then and the envy of the village. Grandfather Panganayi was a rural agricultural extension worker who rode a mudhudhudu round Charter district working for the Rhodesians until he’d made enough money to build his own home. You remember he was proud of that house, the only one in the compound with a real bed and fancy furniture, whose red floor smelled of Cobra and whose whitewashed walls looked stunning in the sunlight compared to the muddy colours of the surrounding huts, just as he was proud of the wireless he’d purchased in Fort Victoria when he was sent there for his training. Through his wireless radio with shiny knobs that no one but he was allowed to touch, the marvels of the world beyond your village reached you via shortwave from the BBC World Service, and because you didn’t speak English, few of you did, the boys that went to school, not you girls, Grandfather Panganayi had to translate the words into Shona for you to hear. In one of those news reports, it was only one of many but this one you still remember because it struck you, they said an American — you do not remember his name — had been fired into the sky in his chitundumusere-musere and landed on the moon.

And so you looked up in the night sky and saw the moon there and tried to imagine that there was a mortal man someplace beside the rabbit on the moon, but try as you might you could not quite picture it. It seemed so foolish and implausible. You thought Grandfather Panganayi was pulling your leg; that these nonsensical words he had uttered were in jest and that perhaps was what he did all the time on those nights you gathered around his wireless listening to those crackly voices, the static and hiss, disrupting the quiet. But you kept this all to yourself. What could you have known, you who then could neither read nor write, you who had never been to Enkeldoorn or Fort Victoria, let alone seen Salisbury, you whose longest journey was that one travelled from your parent’s kraal, fifteen miles across the other side of the village to come here when you got married. The wedding — now that was a feast! The whole village turned up, as they do. So Grandfather Panganayi was really your grandfather-in-law but you cared for him as much as your own because the bonds of matrimony and kinship meant everything here.

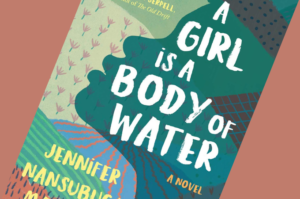

One day when you were young, much younger than on the night of that insane broadcast, only a little girl really, you were sat on the floor of the kitchen hut. Yes, that one at your parent’s homestead that looks exactly like this one over here, the one with the black treated cow dung floor with a fireplace in the centre and benches on the fringes. The one with thatch darkened by smoke and a display unit with pots, pans, calabashes and gourds, one of which held the mahewu Grandmother Madhuve, your real grandmother, offered to you in a yellow metal Kango cup, and you clapped your hands like a polite little girl before you received it and, said, “Maita henyu, gogo,” then drank the bitter, nourishing brew. It was on this day she told you about her people, who were not your people since you were your father’s child and therefore of his people, just as your children were not of your clan but of your husband’s, an offshoot of the Rozvi whose empire that had ruled these savannah plains back when people wore nhembe and carried spears and knobkerries. Long before the time of wireless radios and the strange tongues that rang out from them.

You stop and rest against your cane, because the dog has barked and it is now running towards you from some place in the darkness. The sound of its paws against the bare earth tell you it is coming from the grove of mango trees near the granary to your left. It growls then slows down seeing you, wags its tail and comes nearer. There’s no intruder to fight.

“Kana wanga uchitsvaga mbava nhasi wairasa,” you say, as the mongrel brushes affectionately against your leg.

A firefly sparks bioluminescent green against the darkness of the compound. You don’t need a light, you know every inch of this ground well. Careful now, there are fissures where rainwater has run towards the river, eroding the soil. See the dwala rise up just ahead. That’s it, plant that cane in front of you and tread lightly. Then you remember the story Grandmother told you about the Rozvi emperor Chirisamhuru, because. . . His name meant the small boy who looks after the calves while the older boys herd cattle, or, less literally, one who minds trivial things, and his parents must have understood his true nature even as a child, because once he found himself master of the savannah plains, he set his mind towards nothing but his own comfort and glory. Wives — he had plenty, meat — he ate daily, beer — was his water. Still, none of the praise poets and the flatterers that overflowed his court could satiate his incredible ego.

And so Chirisamhuru sat, brooding in his kraal, the gold and copper bracelets he wore bored him, the silver adorning his spear meant nothing, and the comforts of his leopard skin nhembe were no longer enough to make him feel great, neither were the caresses of his beautiful wives, for he needed his subjects and the world beyond the tall grass kingdom to know he was the mightiest emperor who’d ever walked the Earth. His advisors, seeing their lord thus filled with melancholy, deliberated for many days until they had a plan. Those grey-haired wise men representing all the clans in his empire came and crouched before Chirisamhuru and presented their proposal. With his leave, the Rozvi would plunder the heavens and present to their emperor the moon for his plate. So that when the peoples of the world looked up into the moonless night they would know it was because the greatest emperor was using it to feast on. When Grandmother told you this story, you were at the age where it was impossible to discern fact from fiction, for such is the magic of childhood, and so you could imagine the magnificent white light radiating from a plate just like the Kango crockery you used at your meals.

Here you go over the dwala. Turn away from the compound and carefully descend down the slope, mindful of scree and boulders, for your home is set atop a small granite hill. Now you carry on past the goat pen. You can smell them, so pungent in the crisp air. The cock crows, dawn must break soon. The others still aren’t up yet. Only witches are abroad this hour, you think with a chuckle, stopping to catch your breath. It’s okay, your children have all flown the coop or you have buried them already so now you live with a disparate caste of your husband’s kinsmen, rest his soul too. The three eldest boys left one after the other, following the railway tracks south across the border to Egoli where there was work to be had in the gold mines in Johannesburg or the diamond mines at Kimberley, just like their uncles before them. There they toiled beneath the earth’s surface, braving cave-ins and unimaginable dangers. None of them ever came back. Not one. All you got were telegrams and letters containing the occasional photograph or money that they remitted back to you here in the village to support you. You would rather have had your sons than those rands anyway. What use did you have for money in this land when you worked the soil and grew your own food; here where the forests were abundant with game and wild fruits and berries and honey, the rivers and lakes brimming with mazitye, muramba and other fish. Their father, rest his soul, drank most of the money at the bottle store in the growth point anyway and still had enough left over to pay lobola for your sister-wife sleeping in one of those huts yonder. You did alright with your four daughters, they married well, finding good men with good jobs in the cities. The youngest boy you buried in that family plot there since he could not even take to the breast. At least there are the grandchildren, some who you’ve never seen and the precious few you seldom see.

In the meantime, you linger — waiting.

Adjust your shawl, the nip in the air is unkind to your wrinkled flesh that looks so grey it resembles elephant hide though with none of the toughness. You forgot to wear your doek and the small tufts of hair left on your head give you little protection. You really ought to turn back, go to the kitchen, light a fire and make yourself a nice, hot cup of tea. After that you can sit with your rusero beside you, shelling nuts until the others wake. But you’re stubborn, so on you go — mind your step — down towards that cattle kraal where the herd is lowing, watching your approach. The wonderful scent of dung makes the land feel rich and fertile. No one need ever leave this village to be swallowed up by the world beyond. Everything you could ever want or need is right here, you think as you stand and observe the darkness marking the forest below stretching out until it meets the stars in the distance, there, where down meets up.

Come on now, this short excursion has worn out your legs. Gone are the days you were striding up and down this hill balancing a bucket of water from the river atop your head every morning. That’s long behind you. There you go, sit down on that nice rock, take the weight off. Doesn’t that feel nice? The dog’s come to join you. Let him lie on your feet, that’ll keep them warm. Oh, how lovely. Catch your breath — the day is yet to begin.

You reach into your blouse and search inside your bra, right there where you used to hide what little money you had because no thief would dare feel up a married woman’s breasts, but now you pull out a smartphone. Disturbed, it flicks to life, the light on the screen illuminating your face. So much has changed in your lifetime. The world has changed and you along with it. You were a grown woman by the time you taught yourself to read — can’t put an age to it, the exact date of your birth was never recorded. You pieced out the art of reading from your children’s picture books and picked up a little English from what they brought back from Masvaure Primary, and then even more from Kwenda Mission where they attended secondary school. Bits and pieces of those strange words from Grandfather Panganayi’s wireless became accessible to you. Now even old newspapers left by visitors from the city to be used for toilet roll are read first before they find their way into the pit latrine. You are not a good reader but a slow one, and if the words are too long then they pass right over your head. But you still like stories with pictures, so when your granddaughter Keresia introduced you to free online comic books, you took to them like a duck to water — the more fanciful the story, the better.

You were ready when your second son Taurai in Egoli sent you this marvel, the mobile, and it changed your world in an instant. Through pictures and video calls and interactive holograms you were able to see the faces of the loved ones you missed and the grandchildren you’d never held in your arms. They spoke with strange accents as if they were not their father’s blood but from a different tribe entirely, yet even then you saw parts of your late husband Jengaenga in their faces and snippets of yourself in them. With this device that could be a wireless radio, television, book and newspaper all in one, you kept abreast with more of the world outside your village than Grandfather Panganayi ever could. More importantly, you harnessed its immense power, and now you could predict the rainfall patterns for your farming. They no longer performed rainmaking ceremonies in the village, not since Kamba died, but now you could tell whether the rains would fall or not, and how much. Now you knew which strain of maize to grow, which fertiliser to use; it was all there in the palm of your hand.

You’ve lived through war, the second Chimurenga, survived drought and famine, outlasted the Zimbabwean dollar, lost your herd to rinderpest and rebuilt it again, have been to more weddings and funerals than you care to recall, seen many priests come and go at the mission nearby, and witnessed the once predictable seasons turn erratic as the world warmed. All that and much more has happened in the span of your lifetime. Indeed it is more useful to forget than it is to remember or else your mind would be overwhelmed and your days lost to reminiscences. And if you did that then you would miss moments like this, just how stunning the sky is before dawn. While you wait for Nyamatsatsi the morning star to reign, some place up there in Gwararenzou the elephant’s walk that you’ve heard called the Milky Way, you can still find Matatu Orion’s Belt, or turn your gaze to see Chinyamutanhatu the Seven Sisters, those six bright stars of which they say a seventh is invisible to the naked eye, and there you can see Maguta and Mazhara the small and large Magellanic Clouds seemingly detached from the rest of the Milky Way. You know how if the large Magellanic Cloud Maguta is more visible it means there will be an abundant harvest, but if the small Mazhara is more prominent then as its name suggests there would be a drought.

Yes, you could always read the script of the heavens. They are an open book.

But now you look down and check your phone, because your grandson Makamba is travelling. He said on the video call yesterday if you looked south you might see him. There’s nothing there yet. Wait. Fill your lungs with fresh air.

Now you recall Grandmother’s tale of how the Rozvi set about to build a great tower so they could reach the sky and snatch the moon for their emperor. It is said they chopped down every tree in sight for their structure and slaughtered many oxen for thongs to bind the stairs. Heavenbound they went one rung at a time. For nearly a year they were at it, rising ever higher, but they did not realise that beneath them termites and ants were eating away at the untreated wood. And so it was the tower collapsed killing many people who were working atop it. Some say, as Grandmother claimed, this marked the end of the Rozvi Empire. Others like Uncle Ronwero say, no, having lost that battle, the Rozvi decided instead to dig up Mukono the big rock and offer it to their emperor for his throne. But as they dug and put logs underneath to lever it free, the rock fell upon them and many more died. A gruesome end either way.

There it is, right there amongst the stars. You had thought it was a meteor or comet, but its consistency and course in the direction Makamba showed you on the holographic projection can only mean it is his chitundumusere-musere streaking like a bold wanderer amongst the stars. You follow its course through the heavens, as the cock crows, and the cows low, and the goats bleat, and the dog at your feet stirs. Makamba said he was a traveller, like those Americans from the wireless from long ago, but he wasn’t going to the moon. He was going beyond that. These young people! He’d not so much as once visited his own ancestral village, yet there he was talking casually about leaving the world itself. So you asked, “Where and what for?” And he explained that there are some gigantic rocks somewhere in the void beyond the moon but before the stars, and that those rocks were the new Egoli. Men wanted to mine gold and other precious minerals from there and bring them back to Earth for profit. Makamba was going to prepare the way for them. If he had grown up with you, maybe you could have told him the story of the Emperor Chirisamhuru and the moon plate, and maybe that might have put a stop to this brave foolishness. First the village wasn’t enough for your own children, now it seems the world itself is not enough for their offspring. In time only old people will be left here, waiting for death, and who then will tend our graves and pour libation to the ancestors?

You watch in wonder the white dot in the sky journeying amongst the stars on this clear and wondrous night. Then you sigh. You’ve lived a good life and there is a bit more to go still. Let your grandson travel as he wills. When he returns, if he chooses to make the shorter trip across the Limpopo, through the highways and the dirt roads, to see you at last in this village where his story began, then you will offer him maheu, slaughter a cow for him and throw a feast fit for an emperor on whatever plate he chooses to bring back with him from the stars. But he must not take too long now. If he is late he will find you planted here in this very soil underneath your feet and your soul will be long gone, joining your foremothers in the grassy plains.

“Ndiko kupindana kwemazuva,” you say. The horizon is turning orange, a new dawn is rising.

Ologe October 16, 2020 05:52

Beautiful!!!