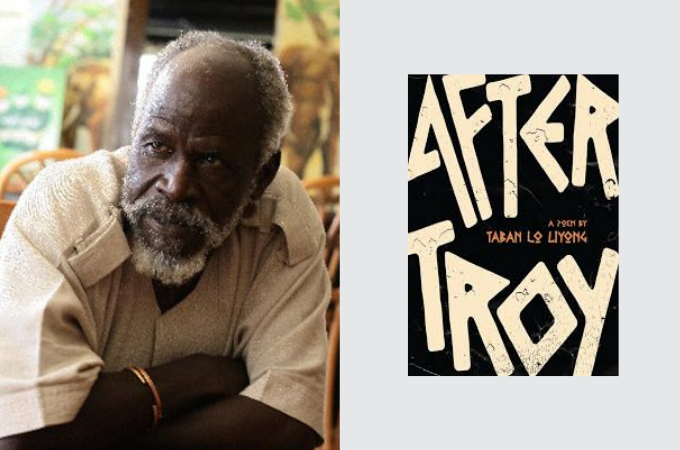

Join South Sudanese/Ugandan writer Taban lo Liyong, journalist and multimedia artist Stacy Hardy, and critic Unathi Slasha in the launch of lo Liyong’s new book, after troy.

after troy is a book-length poem. According to its publisher, Deep South, it is

an expansive and engaging elaboration of two classical Greek texts, Homer’s Odyssey and Aeschylus’s Oresteia. Its focus is the homecoming from the Trojan war of two hero-kings, Odysseus and Agamemnon. Lo Liyong recreates their thoughts and speech, adding dialogue from other characters, most of them women, who are not given a voice in the original stories. after troy is also a philosophical enquiry into retribution and justice.

The conversation will take place via Zoom on January 30, 2021 at 6pm GMT+2/ 7pm GMT+3/ 11am EST.

To join the conversation, send your name and email address to [email protected]. You will receive a Zoom link on Friday, January 29, 2021.

Taban lo Liyong is the author of over twenty books — poetry, plays, stories, essays, children’s books, literary criticism, and folktales. His work bristles with satire, roguish comedy, and a spirit of defiance. He has taught in universities in Africa, Asia, North America, and Europe, and is currently a professor at the University of Juba, South Sudan.

Here is an excerpt of the poem and lo Liyong’s afterword:

***

she who comes to me as in a dream, or in many disguises is a

goddess; they say she had no mother: both her father and mother were zeus’s mind:

the chief god conceived her and out of his mind, out of his head,

she emerged sans childhood, sans wet-nurse, sans milk teeth

athena of the dawn-grey eyes and divine skin, athena whose eyes

pierced you through since she x-rayed you;

athena, child of mind, conceived as an idea in the mind: the very

fruit of intellecting, patron saint of thought

athena, a goddess, but as capricious as any earthbound princess,

rivalling her brother apollo, was with me.

me, the boy whose childhood was lost since i was the last kid, and

had no elder sibling either,

when i looked into those dove-grey eyes, i stopped thinking and

let her words sink into my being,

if there was beauty, human body shaped, whose presence stopped

my breath, it was she, my athena, i was awash with you

***

This national hero of Achaia, Odysseus, is a complex character. Pragmatic as he is, he will lie, cheat, and murder for the sake of Achaia, and return to her. Everything Odysseus does in the Iliad and the Odyssey points to the qualities Achaians approved in their heroes: duty to the state first, second, and third. Fight all gods and men, adopt temporary peace or truces with gods, goddesses, spirits, men and women: anything to get what you want.

In Penelope resides the quality of the Achaian public woman: faithful to her husband, gentle but firm in discouraging suitors, clever enough to make up stories to protect her virtue. Married early, then left to tend little Telemachus, the wife of a soldier missing in action, she was besieged by Achaia’s best suitors – the men who do not go to war but feast on the heroes’ wealth.

Picture the evening when Odysseus, his son Telemachus, and his shepherds and house servants had just killed all the suitors, including Antinoos, who was generous and would have been the one favoured by Penelope had Odysseus not returned. Imagine Odysseus that evening, tired from the carnage, sitting in the hall with his war gear and bloody hands. Look now at Penelope trying to reconcile herself to the inevitable: this stranger, whoever he is, now demands to be accepted as her Odysseus back from war. But she has a final test to put to the stranger, the test which will reveal to her whether the man in front of her is an imposter or not. In my poem I verbalize Penelope’s silent thoughts, follow the thread of her musings.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions