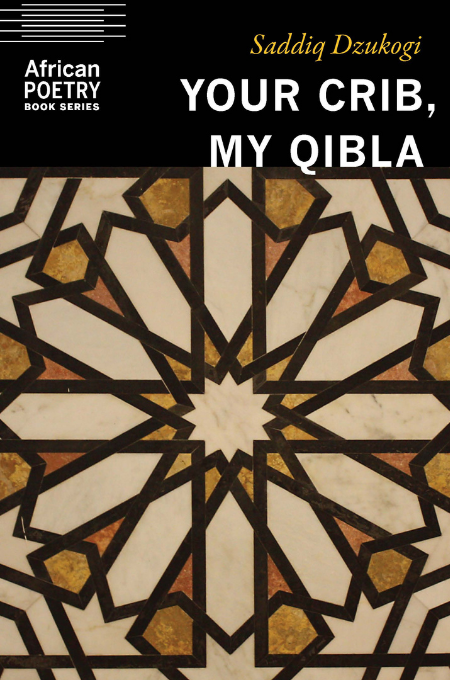

If you follow Saddiq Dzukogi like I do on social media, you’ll be familiar with the different times he pays tribute to his daughter, Baha. In the poetry collectionYour Crib, My Qibla, Dzukogi chronicles the grief of losing a loved one, but of note is how the collection keeps the dead alive through streams of memory and artifacts.

In bringing presence to what can no longer be present, the persona holds onto items—now treasured relics left behind by the one-year-old. Through them, the persona holds her, touches her, and feels her in places and things she once inhabited. He tucks into his bag the napkin once used to wipe the girl’s face after she ate; he buys shoes she’ll never wear; he searches until he finds the ribbons that held up her hair in colorful knots; her “crib [becomes] his cathedral.”

In “Scarf” Dzukogi writes:

He can’t explain just how sacred an act

sniffing your clothes has become.

Like the physical items, memory too drives this poetry collection. There’s a relentless combing of the mind for recollections of what once was; a desperation to touch and possess every detail of what is remembered of the dead. Memory is how the persona resurrects his loved one. Memory is what the persona can’t afford to lose, like he lost her. He “smells the floor to sense her scent” and “answers to everything that reminds him of her.” As Dzukogi writes in “The Fruit Tree,”

He stays in the company of all her toys

as he remembers how she clutches each

by the tail. It is her way of keeping in touch.

This poetry collection, to be released in March 2021 by the University of Nebraska Press, is sharp in grief as it is in defiance of the cause of grief—death. The refrain “Today Baha is not dead” appears five times, a regularity that chips at the sharpness of loss and normalizes the alive-ness of the girl, regardless of the form in which she exists. The declaration of life upon the dead speaks to the power of memory that the poet invokes, the sacredness of relics that were once ordinary things, and a refusal to believe that death is the end of connection with those we once shared life with. This is captured in the poem “Marshmallow”:

Today Baha is not dead; she is six years old,

forcing marshmallows into his mouth.

Says I’m grown enough to feed you, Abba,

with the future, that’s what she calls him,

just like her brother.

In the first part of the collection, “Your Crib,” the reader is served the most intimate aches, treasures and hopes of the persona, even when the point of view avoids the “I” narrative. The first poem, “Wineglass,” starts with an address to the subject, “When your mother found strands of your hair/hung up in the teeth of your comb,/your father squirreled them into a wineglass.” The connection between persona and subject is held alive through recollection, tribute, and relic. We hear the persona speak and his voice echoes back at him.

The second part of the book, “My Qibla,” introduces dialogue between Abba and Baha, another way the poet immortalizes the dead. The words are not that of a typical one-year-old per se, but we get transported to the other side to see, hear and touch what resides and transpires there. If the dead had memory, what would it be about? The “I” narrator is active, and we learn of the things Baha longs for; she misses her father “cleaning the dirt in my ears” and wants him to “Hold me down in your body”.

In “Observations,” we read Baha’s wish for a journey back in time:

Ba, I’m praying

that a hummingbird hands me its ability

to hover and fly backward,

back into a timepiece where I am

myself in a bathwater

you prepared.

But the dead comfort the living too. Baha tells Abba “Do not let your body continue as a village, sacked and burned”. This consolation adds to the claim to immortality that this collection garners for; through recollection, through artifacts, through a declaration of life upon the dead using language.

Reading Your Crib, My Qibla indeed feels like being inside a cathedral; sometimes joyful voices rise in praise and worship, other times dirges fill the room, and almost every time, assurance sprinkles forth from the pew about a life that can continue to live, even in death.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions