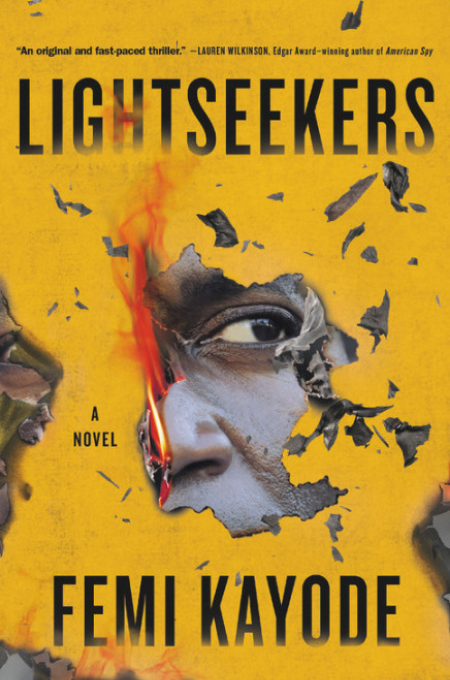

SOURCE

The October sun is as hot as the blood of the angry mob.

John Paul follows the crowd as they chant and push the three young men. They’ve been stripped naked, their scrotums shrunken from fear as the beatings result in wounds that will never become scars. Sticks. Stones. Bricks. Iron. Bones break, blood flows. Tearing flesh draws short-lived screams from tired lungs. The men fall but are swiftly pulled up and dragged through the streets, towards a place no one picked out, but everyone seems to know.

It rained the day before, making the red earth muddy in several places. When the young men fall here, they’re kicked further into the ground; their blood mixing with sludge. By the time tyres are thrown over their heads like oversized necklaces, and the smell of petrol wafts so strong that some in the crowd cover their noses, madness has staked its claim on what is left of the day.

The strike of a match births flame as a brick crushes the skull of one of the men, leaking brain matter and life, so he doesn’t howl and writhe like the other two, when fire starts to lick their skin and hair.

The phone thrums in John Paul’s hand. The battery indicator flashes red. He lowers the smartphone and looks around. He’s not the only one bearing digital witness to the execution in progress. He considers using the cell phone he had taken off one of the burning men before the mob pounced, but the irony wouldn’t be worth it. It’s over anyway. Time to go.

As John Paul walks away, I follow him in the shadows, unable to unsee the nightmare he created behind us.

And because he doesn’t look back, neither can I.

ACT ONE

light reflects in several directions when it bounces off a rough barrier

THE WHY, NOT THE WHAT

Unless I’m mistaken, a riot is about to break out in the departure lounge of the Lagos Domestic Airport.

‘Someone should at least tell us what’s going on!’ an irate passenger barks into the face of an unruffled airline staff member, spraying her with spit.

Good luck with that, I think from where I sit with my meat pie and Coca-Cola. I’m at a table in the Mr Biggs’s restaurant opposite the 9ja Air check-in counter, a position I carefully chose so I won’t be left behind when the delayed airplane finally decides to fly to Port Harcourt.

‘Sir, the flight is delayed,’ the staff person repeats. ‘I’ve told you –’

‘What’s delaying it?’

‘I can’t answer that, sir. If you’ll be patient –’

‘For how long?’ This question is from another sweaty passenger who has no right to be this frustrated, considering I saw her come through the entrance less than thirty minutes before the flight was supposed to have departed. ‘We’ve been waiting for … ’

Three hours, seventeen minutes. But if you count how long since the Uber dropped me at the airport, it would be five hours plus. I suppose the other passengers weren’t running away from their homes to avoid a confrontation with their cheating spouse. Okay. Likely cheating spouse. Truth is, the hurried way I packed my bags and left home in the early hours of this morning had little to do with punctuality and everything to do with my unwillingness to ask my wife the question that was uppermost in my mind.

Are you having an affair?

It had taken a lot of willpower to tamp down that question this morning, as Folake stood in her light cotton housecoat, arms akimbo. Her long locks were pulled back from her face, so there was no masking her disapproval as she watched me pack.

‘You’re really doing this?’

‘Yes,’ I grunted and made a show of counting some underpants.

‘And it doesn’t matter that I think it’s a bad idea?’

I placed boxers in my suitcase and responded in what I hoped was a well-crafted, neutral voice. ‘We’ve been through this, Folake.’

‘You’re not a detective, Philip.’ She stressed my name in the way she does when she’s trying, unsuccessfully, to hold on to her patience.

‘Your faith inspires and motivates,’ I replied ruefully.

‘Don’t play that card! No one has shown more faith in you than me.’

‘You reckon now’s the time to stop?’

‘You can’t go off to some village to solve a case that’s been cold for more than a year and expect me to throw a send-off party.’

I faced her, finally making eye contact.

‘I’m not solving anything. I’m investigating why what happened, happened.’

‘How’s that not solving a case? Surely you can’t understand why something happened without knowing what happened?’

Had I gone into an explanation of my work as an investigative psychologist, I wouldn’t be here waiting on a delayed flight. Despite supporting each other through our respective PhDs, my wife pretends to misunderstand my work when it suits her.

‘Folake, this is an opportunity to put my skills to use in the real world –’

‘A real and dangerous world,’ she cut in sharply.

No doubt travelling to Okriki might be considered dangerous for someone like me, who until eight months ago had spent the better part of his adult life in the States, but it would’ve been nice if my wife had said instead: ‘Go, Sweets. If anyone can find out what led to the mobbing and burning to death of three undergraduates, you’re the one. You’ve got this.’

‘It’s a foolhardy scheme, and you know it! I don’t know what you’re trying to prove.’

‘That I’m more than a two-bit academic without tenure,’ I shot back, restraining myself from shouting.

‘Leaving your family to go investigate multiple murders isn’t going to get you tenure,’ she said, no less strident.

But it’ll take my mind off the sad possibility you’re cheating on me.

Of course, I didn’t say this out loud. I hate fighting, especially when it involves raised voices. Moreover, there aren’t a lot of people who can hold their own in a war of words with Professor Afolake Taiwo, the youngest Professor of Law at the University of Lagos. In almost seventeen years of marriage, I’ve rarely won an argument with my wife.

‘Okay, Philip. Let’s say you get there and you find out what really happened, or why it happened. What then? What do you want to do? Write a book?’

‘This is Nigeria, Folake,’ I scoffed. ‘You don’t chase down the details of a mob action in the hopes of writing a best-seller.’

‘Then in the name of everything holy, tell me what you’re hoping for?’

‘I told you the father of one of victims hired me to –’

‘Yes, yes, I know.’ She threw her hands in the air and rolled her eyes. ‘He wants you to write some report because he doesn’t believe his son was a thief, even though it’s all there on social media.’

‘Have you seen the video?’

Folake shuddered.

‘I’ve watched it a hundred times at least,’ I continued, to stop her from recounting what she must have seen on any of the several sites where the deaths of the Okriki Three were posted. ‘And you know what? Every time the same thought goes through my mind – people can’t be so crazy as to burn three boys in broad daylight just because they are caught stealing.’

Folake sat on the bed, shoulders slumped, and I wasn’t sure if it was from our argument or my reference to the distressing video.

‘Nothing makes sense in this country,’ she said, shaking her head.

‘Everything makes sense when you know why people do what they do.’

‘Psychobabble nonsense,’ she snapped and her hand rose quickly to her mouth as if to take back her words. She’d crossed a line and she knew it.

I made a production of zipping my suitcase till I was sure I could keep my face impassive. When I looked at her, my voice was as neutral as when we started the conversation.

‘Thank you. Now I’ll go apply my psychobabble on a matter for which I’m going to be well rewarded. Excuse me.’

I lifted the suitcase and walked out quickly before she gathered her wits.

Another passenger’s angry voice breaks through my reverie. ‘This is unacceptable! Only in Nigeria is this kind of –’

I give it another hour or so before irate passengers and rude airline ground crew exchange blows. For now, I turn my attention to the one thing I am trained to understand.

A crime scene.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions