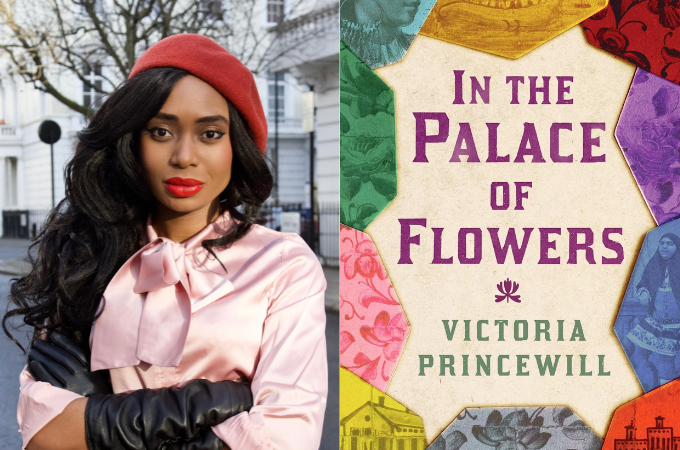

Victoria Princewill’s debut novel explores the life of a captivating though little known historical figure. Titled In the Palace of Flowers, the book unearths the untold story of Jamila Habashi, an Ethiopian woman who served in Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar’s royal court at the turn of the 20th century. In this interview, Princewill talks about what drew her to Jamila’s story, why she loves historical novels, and the need to enrich the representation of global black experiences.

Brittle Paper

Hello Victoria. It’s nice to finally chat with you about the new book. Congrats, by the way. What does it feel like to finally have In The Palace of Flowers out in the world?

Victoria Princewill

Thank you! It feels very surreal. Yesterday I went to Libreria, a bookshop in London that was stocking copies of my novel. It was strange to see it in the company of other published works and to be honest, I was quite emotional.

Brittle Paper

How long did the book take from drafting to publication? Were there any memorable moments in the drafting process?

Victoria Princewill

It was quite a journey. I first began writing the novel when I was 26 and whilst it was meant to come out last year when I was 29, due to COVID, it has come out a year later. It has been a labour of love and I have been simultaneously impatient to see it out in the world, and also the closer we got, the more I was in danger of editing it to death.

As to memorable moments, early on as I read the comments from my editor, I would shake my head at the changes requested, feeling very misunderstood. But when I printed the manuscript and read it in my hands, I could see the need for almost every change suggested. Between each draft I would print off and reread a full 100K words again, whereas before I would have thought it tiresome. Reading from the hard copy was necessary because writing a novel requires real precision and the nuances can be missed when reading online.

Brittle Paper

In The Palace of Flowers is a fictional re-imagining of Jamila Habashi’s life, an Abyssinian woman who served as a slave in a 19th century Iranian court. How did you first come to know about Jamila’s life, and why did you think her story had to be told?

Victoria Princewill

I came across her own first-hand account of her story in an academy paper by Anthony A Lee. She had written a letter that detailed her existence but only really her ancestry, her status as an enslaved woman in Iran and the men between whom she was sold.

Hers was the only readily available story and the mere fact that it had survived when there was a concerted effort to erase the history of Abyssinians in Iran made me determined to do justice to what I took to be her own perseverance and to give her the humanity she had been denied.

Brittle Paper

After you decided on telling her story, how much research did you have to do to reconstruct late 19th century Iranian royal court life?

Victoria Princewill

Oh, it was a lot of research! I wanted to do justice to Jamila and to the people who lived in that period. I also wanted to contribute to contextualizing the presence of Black Iranians who might come across my book. I am not from Iran and to write about a different culture and history, especially one that took place in the past is an endeavor I believe one has to approach with humility. So, it was important to me to be as scholarly and precise as possible in my research. Thus, when I chose what to include, what to take out, what to change, and what to fictionalize, I was not doing so from a place of error, but from a choice to centre the storytelling over the history.

I consulted with Pedram Khosronejad and Anthony A Lee, both of whom are subject area academics; Pedram is a visual anthropologist and Anthony is a historian. I was directed by Anthony to Taj Al-Saltana’s autobiography, Crowning Anguish. Taj was the daughter of Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar and so her memoir was essentially a gold mine of nuanced information I could not find elsewhere. Pedram supplemented my own research with additional essays but also provided access to his trove of formerly archived photography taken by the Shah at the time.

Brittle Paper

In the novel, Jamila is a deeply contemplative figure. Why did you give her such philosophical depth?

Victoria Princewill

It seemed natural that the complexity of her life would lend itself to an extraordinary number of questions. I wanted to centre the questions that would be plausible to her and not to an outsider. But I think having an inquisitive mind is quite natural, being critical, skeptical, and not taking things for granted is also likely for the kind of character one might be forced to develop when made so vulnerable at such a young age. But she is not simply reactive, she is philosophical and thoughtful as you rightly point out. There is perhaps a personal bias there, where I wrote in certain qualities that felt normative to me. Being philosophical and surrounded by people who are not tends to heighten the contemplative experience and is simply the life I have lived, and given the ideas I wanted to probe, it seemed fair to bring it into the story.

Brittle Paper

Some of the plotlines are tied up in some of the most fascinating love triangles. What would you say is the place of love in a story like this?

Victoria Princewill

I don’t think love has or need a ‘place’ anywhere. It simply is. It grows from intimacy and connection; it grows sometimes out of pain and harm. Pain and harm are so easily and frequently foundations for intimacy and connection. So, it felt organic to place it here as anywhere.

Brittle Paper

In your bio, you describe yourself as a historical novelist. What do you like about the genre of historical fiction?

Victoria Princewill

I like the possibility it holds. The more history I read, the more I am stunned by how rich and varied the world has been compared to the flattened narratives that are told, especially in the west. Given the way globalization works, these are the stories that are loudly trumpeted everywhere. Historical fiction allows us to take the forgotten stories and bring humanity into them, into the lives of those who lived and haven’t had that recognition. I think it is also useful for young people growing up, to not simply dream of what they might long for, but know what could be, based on what has gone before.

Brittle Paper

As someone who has thought a lot about women’s lives in other historical periods, what would you say has changed or stayed the same in the representations of African or black women in storytelling?

Victoria Princewill

I think that change is always contingent on access, on publishing and also on perspective. I can ultimately only talk about the perspective of the diaspora like myself and our access to the stories of African and black women in storytelling. To me what has changed the most is the ease with which one can access African stories and not simply west African, or African-American narratives. I think publishing houses like Cassava Republic and ultimately agencies like Pontas, both of which I am signed with, have been instrumental in broadening the space for a breadth of stories to be told. I do think we are seeing a geographical shift in which stories enter the mainstream. I think people are interested in the variety of stories and journeys from the African world that’s not only centered on the Atlantic Ocean or the American gaze.

Brittle Paper

How might the novel contribute to conversations about transnational black experiences and black Iranians more specifically?

Victoria Princewill

I spoke with the Collective of Black Iranians virtually and they talked to me at length about how they have not ever been portrayed in story as central characters prior to this novel. I think their partnership with Because We’ve Read, which spends a year reading transnational black stories, starting with In the Palace of Flowers, is a phenomenal way to make global the project of understanding the breadth of black experiences, and the extent to which blackness is both a historical and global political reality. I think In the Palace of Flowers, given how far it is from the west and given its gaze is centered on those who have African heritage and live under Iranian and Islamic rule will help uncoupled blackness from Euro-American capitalist narratives. It reaffirms the nuances we must never ignore.

Brittle Paper

In the hours following Meghan and Harry’s interview, you shared thoughtful comments on racism and the culture of royalty. Do you see any parallels between Harry and Meghan’s story and your depiction of the Shah’s court in late 19th century Iran?

Victoria Princewill

Yes and no. I think one of the striking moments in the novel was based upon something I read that took my breath away. I have the Shah refer to a long dead right-hand man of his, a Premier who was brilliant for the country and had been his tutor. Now the Shah had greatly admired this person, Amir Kabir and had had him executed nevertheless. This all took place prior to the scope of the novel and is not a spoiler, but I was struck by how such a close bond and a positive impact could result in such a tragic end. In the novel the Shah notes how there is danger in being the Shah’s closest confidante, the one who is the best at the job. The rest of the court gets jealous, and an abundance of dissenting voices overpower that of the advisor who suffers the consequences. Now whilst Meghan and Harry’s lives are nothing like those of the Shah and his court, what struck me was that Harry had commented on how Meghan, like his late mother Diana had come into the British Royal Family and essentially done the job too well and thus found herself unwelcome. This correlation between the high competency of one and envy of the rest leading to the expulsion (or in the Shah’s court, execution) of the highly competent is, I think, a casualty of monarchy and inherited power. In most spheres where one has to be qualified, competency is an asset. Where one is simply favored, or entitled, the presence of competency threatens to expose the mediocrity of everyone else. So those are my thoughts on that.

Brittle Paper

One of the most striking aspects of the novel is the setting, to which you give careful architectural attention: the grand bazaars, the gardens, the harem apartments. There were moments when it felt as though we were in a scene from Walt Disney’s Aladdin. What went into configuring the novel’s fictional world?

Victoria Princewill

I am glad you feel that way because my goodness the number of books I had to consult on the architecture of the time, on which buildings still stood looking as they did versus which were being refurbished… it was a myopic period for me! But thankfully there were the diaries of travelers to Tehran and once again the memoir of Taj al-Saltana proved indispensable, especially regarding the harem, the insights were truly unparalleled, and so casually provided!

Brittle Paper

Thanks, Victoria, for taking the time to chat with us!

Victoria Princewill

The pleasure is all mine.

***********

Buy In the Palace of Flowers: Cassava Republic | Bookshop | Amazon

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions