African literature has long deployed the prison as a space of containment and resistance imbued with the contradictory emotions of love and hate. The rich genre of African prison narratives spans Wole Soyinka’s The Man Died (1972) Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Detained: A Writer’s Prison Dairy (1982), Nawal al-Sadaawi’s Woman at Point Zero (1975) and Memoirs from the Women’s Prison (1984), Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom (1994), and, recently, The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela (2018). Letters written by political prisoners convey the experience of imprisonment with an unmediated rawness and intensity than other reflective and often crafted forms such as memoir, autobiography, and diaries. Till the Time of Trial: The Prison Letters of Simon Nkoli, a selection of letters between black queer anti-apartheid activist Simon Nkoli and his partner Roy Shepherd during his incarceration and trial, offers a unique perspective on prison writing as a love letter and a form of activist self-fashioning.

Black gay activist Simon Nkoli emerged as a student organizer and a leader in the Vaal Civic association in South Africa in the 1970s. These activities put him on the radar of the apartheid authorities. A few years before his arrest he had joined the Gay Association of South Africa, a predominantly white organization, where he was one of the few black members. During a peaceful protest against rent increases in the Sebokeng township, South African forces attacked the protestors leading to several deaths, among close associates of Nkoli. Nkoli and twenty-one others were arrested on the specious charge of conspiracy and treason against the state while attending the funeral of their associates. Among those arrested were the “Big Three,” leaders in the African National Congress Moses Chikane, Mosiuoa “Terror” Lekota and Popo Molefe, who assumed key roles in the post-apartheid government. The trial lasted for three years, and during this time, Nkoli maintained a steady correspondence with those outside: his lawyers, Roy Shepherd, and several international organizations including the Scottish Human Rights Group, North American and European gay and human rights organizations, Amnesty International, and the International Gay and Lesbian Association. Nkoli’s homosexuality, and the visibility he had gained as a black gay icon, brought the kind of attention to the Delmas Trial that made his fellow accused initially consider a separate trial, uncannily mirroring Gay Association of South Africa’s lack of support to Nkoli during his imprisonment.

The selection of letters published by the Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA), documents, at least on the surface, Nkoli’s interest in clothes, music, and books and contains brief references to his isolation when he came out to the Delmas accused, and later, when he was diagnosed with AIDS. These heavily excerpted and sometimes edited letters at once raise questions about the selection process and point to future directions of enquiry. The Nkoli collection is one the centerpieces of the LGBTQ+ archive at GALA (Chernis 2016). While the GALA selection indicates a black queer self-fashioning that Nkoli would deploy successfully in the organization GLOW (Gays and Lesbians of Witwatersrand) after his release, it inadvertently downplays contested, and sometimes contradictory, terrains of Nkoli’s anti-apartheid and gay rights activism based on principles of non-racism, non-sexism, and non-heterosexism.

In terms of genre, the selection is different from the canon of African prison writing: first, it is a sample of a larger archive only parts of which are available in print or online since the formation of GALA in 1997; second, the letters were not intended for publication nor were they compiled in consultation with the author, though the addressee, Roy Shepherd gave the letters, photos and other materials from the Delmas Trial to GALA; and finally, in the words of the former GALA director, Ruth Morgan, Till the Time of Trial was the first publication in a series commemorating “a well-loved LGBT rights activist” standing “powerfully for the idea that human rights cannot be separated.”

Here are some lines of enquiry based on keywords from the letters: body, appetite, faith, and politics. Nkoli’s letters underline bodily needs of food and clothing, as requests or demands, while communicating the conditions under which the Delmas accused lived, and less frequently, the letters offer reminiscences of a shared life. He describes sharing simple meals of dumpling and chicken, beef and baked beans, brown bread, and sour milk. He asks Roy to bring him condiments such as Achar and remembers the meals they would cook together. There are descriptions of the clothes and supplies his family and Roy send him – underpants, jackets, shirts, and ties, pants, deodorant, watch – as well as requests for jeans, ties, and extravagantly, a sky-blue Christian Dior or Carducci suit that he hopes to buy some day. The daily stress of his prison life – as a closeted gay man who came out to his fellow accused, as one accused of murder and treason while preparing for the trial, and as a physically compromised HIV positive man – are revealed in mundane details which become the components of an extraordinary queer self-fashioning. He is connected to other prisoners in bodily requirements of food, clothing, and medicine, and different from them as a stigmatized and later diseased body. One of the most poignant moments in the letter is when Nkoli isolates himself from the other prisoners in a storeroom after being diagnosed with AIDS. One approach to the Nkoli materials thus is through the lens of the body in health and disease in a space which is not conducive to physical or mental well-being.

Reviewing a recent compilation of Nelson Mandela’s prison letters, Rita Barnard writes, “Prison writing always draws attention to the material realm, not least to the materiality of the text itself: the concreteness of pen and paper and the physical conditions of writing and circulation.” The materiality of Nkoli’s letters, written on government sanctioned postcards and subject to censorship, is glimpsed in photographs of the letters. As was typically the case with correspondence of political detainees, there was never any certainty whether the letters would be received by the addressee. Many detainees devised ways to smuggle letters outside through their lawyers and visitors. Some of Nkoli’s letters to Roy were sent extra-legally with the paranoid exhortation that the missives should be destroyed for fear of discovery. Shepherd’s decision to preserve the letters now constituting the ‘body’ of the Nkoli archives allow a glimpse into the specific intertwining of anti-apartheid politics and sexuality.

One aspect of this entwining are Nkoli’s tastes in reading material and music. A steady consumption of romance fiction and women’s writing, among them works by Danielle Steele and Marilyn French, kept him busy and happy while awaiting trial. At one point he writes, “All love stories; no politics for me. No thank you, I have been rehabilitated.” With this casually flippant remark, as with his tastes in food and fashion, Nkoli fashions a self deeply engaged in race and sexuality politics while rhetorically dismissing it. Neither anti-apartheid nor sexuality politics was as easily ignored as the remark seems to suggest. In his vacillations between continuing or rescinding his membership of GASA we glimpse desire to belong to a gay organization and the realization that the organization was not going to support him during his imprisonment. The specific contours of that politics are evident in the pages of Exit, South Africa’s longest running gay magazine, which provides another lens for reading the letters.

Connected to Nkoli’s political trajectory are religious and secular dimensions of faith also casually referenced in the letters. Nkoli and Roy Shepherd met at the Gay Christian Community, and in other accounts of his life Nkoli mentions the dual influence of Christianity and traditional African religions. Quite apart from any religious beliefs the letters display an unwavering faith in a positive outcome of the trial which would allow the two to live together. In the tradition of the romance fiction he avidly consumed, there are declarations of everlasting love, and in one instance, an amalgamation of his and Roy’s last names as a sign of his enduring belief in a happily ever after narrative. The formulaic affect is somewhat undercut by Nkoli’s insistent demands on Shepherd over the three years of his imprisonment. The political trajectories before, through and beyond this prohibited interracial romance – none of Nkoli’s partners were black – merit greater attention.

One such direction would be an exploration of seemingly irreconcilable attributes of intimacy-publicness, the personal-political, race-sexuality that were constantly reiterated in Nkoli’s life and career. In 1980 while a youth activist with the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) where he was secretary of the group’s Transvaal division, the revelation of his sexuality almost led to Nkoli’s expulsion from the organization. In 1983 when the Delmas group learned one of the accused had had sexual relations with another prisoner, Nkoli came out to them. The debates and differences that followed almost led to a separate trial for Nkoli as the group was worried the prosecution would use his homosexuality to complicate their defense. As with COSAS this situation was averted by discussions and debates among the Delmas group. Another coming out of sorts was when Nkoli was diagnosed with AIDS in prison. After experiencing some stigma in prison, he decided to publicly embrace his status as an HIV positive gay man upon his release. The political trajectories of Nkoli’s student activism await a fuller discussion even as his advocacy with the African National Congress to include the Equality Clause in the South African Constitution and AIDS work has been the subject of analysis.

This essay has indicated a few lines of enquiry arising from the slim selection of letters. While Nkoli had initiated a non-racial Saturday group within GASA before he was arrested, it was only after his release from prison that he revived the group and founded Gays and Lesbians of Witwatersrand (GLOW), a very different organization from GASA. The mode of letter writing that he had developed while in prison emerged as a useful rhetorical and political strategy as reflected in Nkoli’s “Open Letter to Nelson Mandela” for the Village Voice, reprinted by Exit. Here he attempts to make the leader understand “what it means to be a gay or lesbian person in the townships” by establishing a direct link to the situation under apartheid where people, feeling unsafe in their home communities, “are moving into the so-called ‘grey areas’ of the white cities, which also happen to be gay areas.” In a savvy move that connects the local to the global or South Africa to the world, Nkoli reminds Mandela of his promises to secure “the rights of all people” on a visit to the Township AIDS Project in Soweto, of his support for gay rights in a meeting in Stockholm, and of the promises made by Mandela’s close colleagues, Thabo Mbeki and Frene Ginwala, who had publicly declared outside of South Africa that gay rights would be secured by the ANC.

Over the past two decades Nkoli’s life and career has yielded many nuanced interpretations, a play, and a documentary film. The tradition of letter writing as an immediate and forceful medium of expression is carried forward by Nkoli’s close associate, Beverley Ditsie whose address, “A Love Letter to my queer Family” describes the continued imprisonment of South African LGBTQ+ activism in the cells of racial and class privilege, evident in the devolution of the Johannesburg Pride March into the Pride Parade and the takeover of the celebration by white organizers. Ditsie reiterates GLOW and Nkoli’s commitment to a “vision of freedom” that recognized struggles across race, gender, social standing or economic status. We can hear that call in Nkoli’s prison letters, its amplification in GLOW and his letter to Mandela, and a resounding augmentation in Ditsie’s love letter.

*********

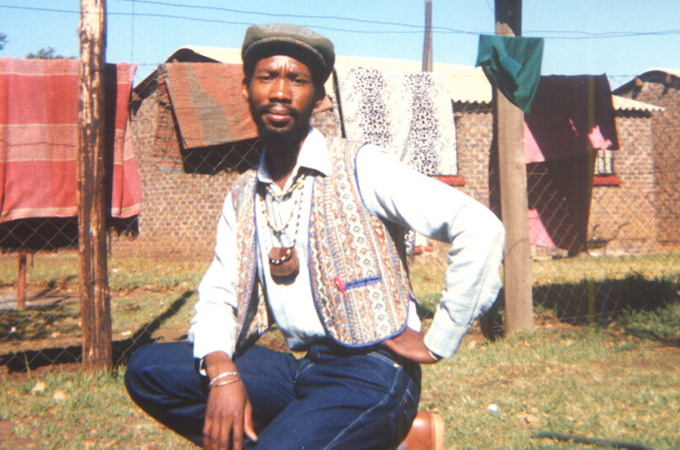

Photo by GALA via tasteofsoutherafrica.com

Richard Libby June 10, 2021 11:16

It has always amazed me how letters have played a role in our global society. It also amazes me that there doesn't seem enough emphasis on them in our younger generations, starting with mine (ostensibly because tech came out that made it easier to write significantly shorter versions and with less flowery language?). Very well researched and glad I learned something new today.