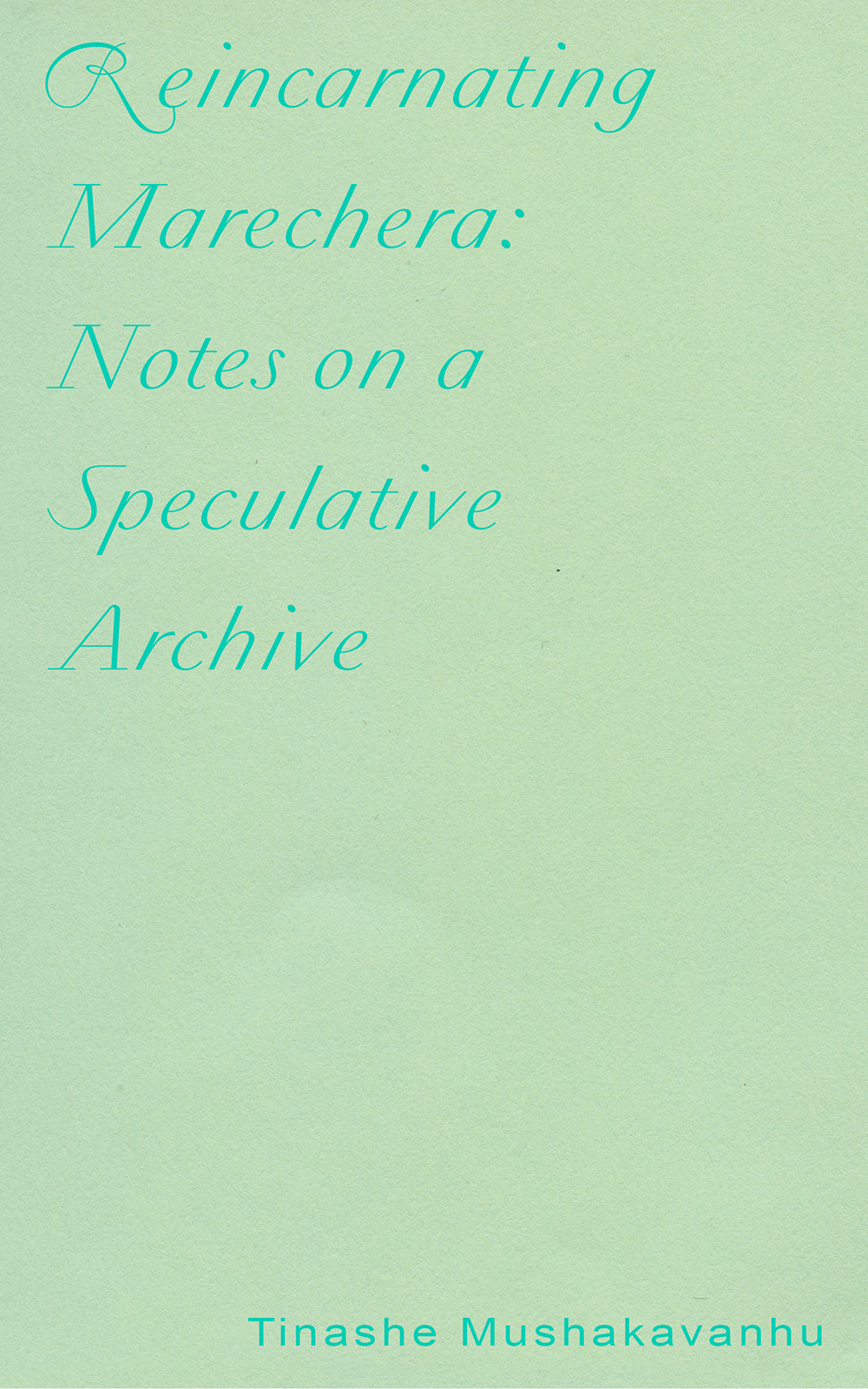

“What do you bring to a dead man, a dead Marechera?” asks Tinashe Mushakavanhu as he sets out to visit Dambudzo Marechera’s grave. Beers? Books? Flowers? Weed? This question about how to properly honor dead revolutionaries is at the heart of Reincarnating Marechera: Notes on a Speculative Archive.

The last decade has seen the passing of many African literary favorites: Chinua Achebe, Pius Adesanmi, Charles Mungoshi, Grace Ogot, and many others. These deaths are saddening, but they also raise questions about our archival practices. How do we ensure that future generations will always have the language to grasp the beauty of the work left behind by the dead? Mushakavanhu responds to the urgency of this question in this utterly beautiful little book about a man who lived the most extraordinary of lives.

Marechera is the Zimbabwean writer who stuns readers with books like House of Hunger. In a moving account that blends creative nonfiction with scholarly insight, Mushakavanhu offers a brand new look at the man behind the myth and the fiction. He interrogates what is implied by the things we say about Marechera. Why we are drawn to reproducing certain myths—for example, that of his homelessness? As Mushakavanhu notes, Marechera was not homeless towards the end of his life. Honoring the dead is about correcting the record. As myth, Marechera’s life eludes us in its full, textured reality. Mushakavanhu attempts a corrective, not by filling all the gaps in our fantasies about Marechera but by bringing him back to life to speak to our moment.

In Mushakavanhu’s telling, the things that make Marechera an outsider paradoxically place him at the heart of his historical moment and ours. Marechera didn’t fit in anywhere. He did not make sense to a world defined by expectations of propriety. Family, country, society were constricting. He also represents all that is radical and category-defying within African literary discourse. Mushakavanhu writes: “Marechera’s writing is a deeply unstable element: its argument does not proceed from point to point but through a sequence of quick, successive bursts and sudden aphoristic shocks. It is an unsettling provocation. This is an important anarchic strategy Marechera employs, a critical mode in which no set hierarchy exists.”

For this, Marechera has been caricatured in the image of the mad artist. Accounts of his life are reduced to repetitions of shocking incidents, some only partially true. Mushakavanhu challenges this idea that Marechera is too strange to be understood. He does this by showing the extent to which Marechera was a voice for young people. Marechera represented their resentment at the failures of decolonization, the corrupt legacies of post-independence world, the “complacency,” the “hypocrisy.” As for his writings, they echo through the whole of African literature. His work infuses African literature with dissidence. Like Amos Tutuola, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Buchi Emecheta, and writers today who are challenging the status quo (and those who are yet to come), Marechera taught the tradition how to rebel against itself. In other words, there is a perspective from which the African literary tradition can be viewed as a series of reincarnations of Marechera. Any person or text that introduces an anarchic element into African literature is a Marechera. As Mushakavanhu shows in the book, this dissidence does not exclude but places Marechera and those like him at the center of African literary history because it is through their resistance to the norm that they “redraft the lines” of what is possible. An account of literary history that centers Marechera is a witness to the revolutionary impulse on which African literature was founded.

The book is a museum of memories. Mushakavanhu collects bits and pieces of Marechera’s past and reassembles them in a space where they can reflect the visionary ideals that informed his life. One of the most powerful moments in the chapbook is the chapter on the collection of letters sent to the Marechera Trust after the author’s death. Some of these letters address the dead writer directly. They are deeply personal and confessional and contain requests for “money…photographs of Marechera, his draft manuscripts, his books, or any kind of memento to remember him by.” The letters came from rural and urban spaces, from the rich and the poor. Marechera wrote books that provoked readers to awareness, but he also clearly touched the lives of readers in ways that far exceeded the promise of literary experience.

In this small but mighty book, Mushakavanhu reconfigures Zimbabwe’s literary and political history around black creative life. “If Dambudzo Marechera had not existed,” he writes, “Zimbabwe would have invented him.” But he also captures the influence of Marechera’s life beyond Zimbabwe. In interviews with Taban Lo Liyong, Ngugi, and China Mieville, these writers share recollections of their encounters with Marechera and the lasting influence he’s had on their thinking. “We have to grateful for what he left with us.” remarks Ngugi, “We are able to continue communing with his real living spirit in the work his has left behind.”

Reincarnating Marechera provides what every ancestor craves: to be seen as a contemporary. He may have died in 1987, but “Dambudzo Marechera has never left.”

***********

If you like what you’ve read about this book, support the author. Follow this link to buy the book.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions