When asked if she feels honored to be the first Cape Verdean woman to have written a published novel, Dina Salústio says that she does not: she feels sad and sorry for the women who came before her and couldn’t write one.

Her answer forces me to consider whether I feel honored to have translated the first novel by a Cape Verdean woman to be published in English.

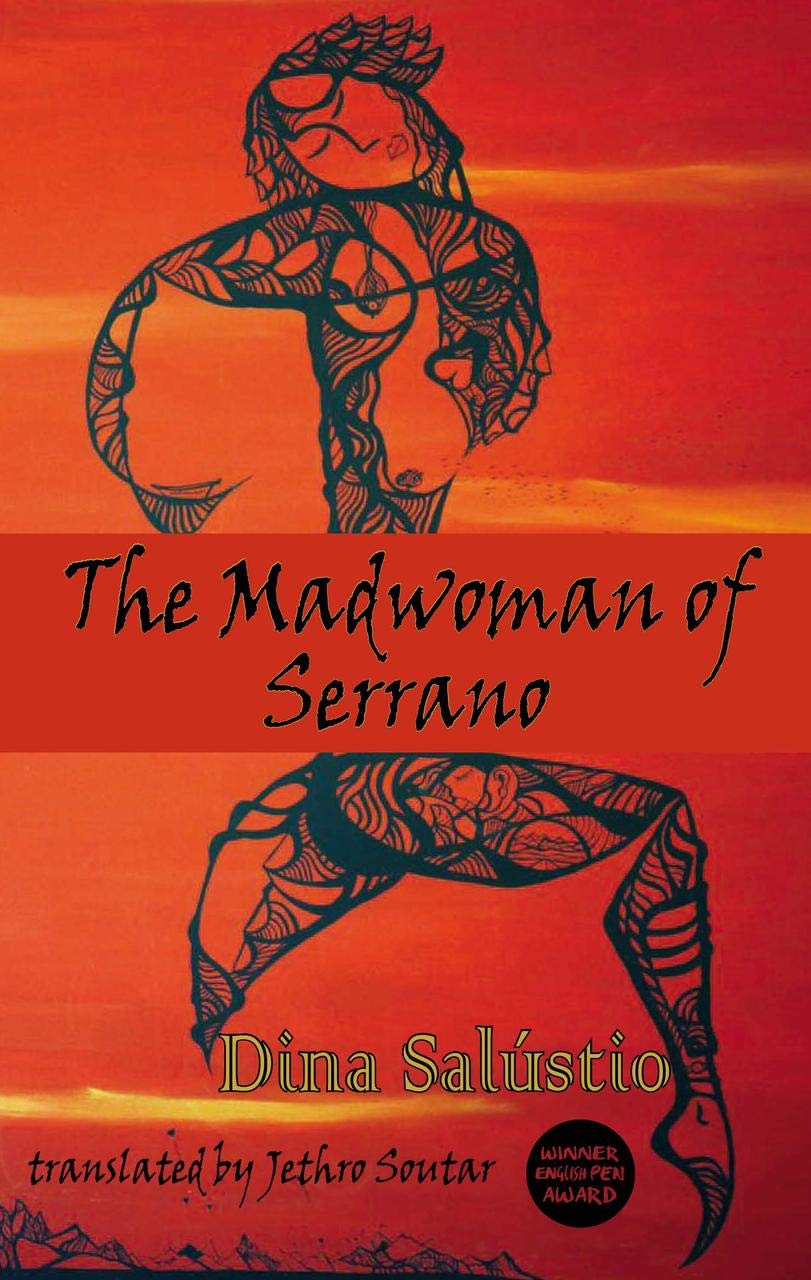

It’s the same book, of course, A Louca de Serrano, published in 1998 by Spleen Edições in Praia, Cape Verde, which became The Madwoman of Serrano, published in 2019 by Dedalus Africa in the UK.

Sometimes ‘firsts’ can be misleading or meaningless labels, but they are perhaps significant here. It says a lot about a place that the first novel by a woman was published just twenty-odd years ago, and it’s no coincidence that The Madwoman of Serrano interrogates gender roles and female disempowerment.

That it took twenty years for the book to be translated into English likewise says much about cultural exchange. Many readers will be aware that few books get translated into English, but they might not have thought about the ones that do, the bias in the system. In countries with developed book industries, networks of publishers, agents, critics and booksellers ensure that promising books come to the attention of foreign publishers. In countries without this ecosystem, it is often translators who perform the task, scouting for talent and trying to awaken the interest of English-language publishers.

Naturally, it is easier to awaken a publisher’s interest if you can dangle the prospect of money before them. Some countries have government-backed funding programs that cover the translation costs for foreign publishers interested in publishing its authors. This is important in that it levels the playing field: publishers can choose which works to publish without having to factor in an extra five to ten thousand of translation costs. (In the US, literary translators are typically paid around 10 cents a word.) The downside is that many countries cannot afford to run such programs, while those that can get to decide which authors to sponsor. It is not hard to see how a dissenting voice from a small African country might not get through.

Dina Salústio is a dissenting voice, and Cape Verde is a small African country. If it is, in many ways, a model of open democracy (Cape Verde regularly ranks highest among African countries on democracy indexes) and a place that holds culture in high esteem, it still lacks the muscle to promote its authors globally, to compete in the soft power literary stakes.

Besides, Salústio is a woman. When she says she feels sorry for the women who came before her and couldn’t write a book, she’s not talking about a lack of publishing opportunities: they couldn’t write a book because they couldn’t write. For a long time, a considerable number of Cape Verdean women were illiterate and Salústio, who turns eighty this year, has no doubt this was a deliberate ploy. Whether enforced by Portuguese colonial overlords or by post-independence governments, the strategy was the same: to deny women agency and deprive them of a collective memory; to prevent their stories from being told.

The Madwoman of Serrano sets out to put this right. Most of the protagonists are women, for a start, but they are also women who defy conventions; knowing their stories might help other women to dare to be different and challenge traditional gender roles.

First amongst them we have the madwoman herself, a mysterious figure who roams the village of Serrano calling out ignorance and making prophecies. The bearer of inconvenient truths, she is dismissed as mad, or louca. This presented me with my first translation conundrum. Many people are familiar with the Spanish word loco; louco is the Portuguese equivalent, which becomes louca in the feminine. There is an economy here that is ideal for a title: you read louca and know instantly that the person is crazy and female. “Madwoman,” on the other hand, is a bit longwinded, even compared to “madman.” I considered gender-specific alternatives — crone, witch, she-devil — but they were all more angry or wicked than madness would imply. As Salústio told me, there is a history in Cape Verde of belittling women by labelling them mad, but also of women projecting madness as a form of self-defense. “Madwoman” is a mouthful, but madness was a concept too important to compromise on. Besides, there is literary pedigree to the term via Charlotte Brontë’s madwoman in the attic in Jane Eyre (a madwoman who is Creole, thus, evoking that same history to which Salústio refers of colonialist representations of black and brown women).

Another key figure in Serrano is the midwife, who delivers babies, helps with women’s troubles and sexually initiates men. Couples have great trouble conceiving in Serrano, which is blamed on the women, but likely the fault of the men. Motherhood is interrogated from a variety of angles, not least the notion that it is a given or the natural order of things. As in Salústio’s short story “Delayed Freedom,” mothers are not automatically enamored of their children, for they represent a loss of liberty. Then there is Gremiana, a woman who does not want children and becomes a pariah, and Maninha, who wants them but can’t have them and is ostracized.

Maninha posed another translation dilemma. A popular name in Cape Verde, it means ‘little sister’, but also ‘barren’. There is no equivalent dual-purpose word in English, let alone one that doubles up as a girl’s name. I might have tried Adriana, with its nod to ‘dry’, or put Arid and pretended it was a first name, but I’m not sure more would have been gained than lost. Translators often like to preserve the names of places and people anyway, as it provides a sense of place: you want the reader to forget they are reading a translation because the prose flows smoothly (assuming it did in the original), but to be reminded of it in passing every once in a while: proper nouns are one way of doing this. Maninha remained Maninha.

Food and drink is another way of providing local color, but there is no mention in the novel of cachupa or grogue, Cape Verde’s national dish and drink, respectively. Indeed Cape Verde is not mentioned or alluded to at all and the book’s language is deliberately straightforward, with no nods or echoes to Crioulo. (Portuguese is Cape Verde’s official language, but Crioulo, sometimes called Kriol or even Cape Verdean, a Portuguese-based creole language, is the common tongue. Salústio says that Portuguese is her tool of transmission; the stories, along with the emotions and memories they contain, come from Africa, from Cape Verde, from inside her.

The relative neutrality of the language in The Madwoman of Serrano is, therefore, designed to give the story universality, even a sense of pan-Africanism. Sometimes a translator has to find creative solutions to complicated wordplay, but sometimes it’s more a matter of being as unobtrusive as possible.

That’s not to say it was an easy book to translate; far from it. The Madwoman of Serrano moves between two worlds: rural Serrano, which is described lyrically and the big city, which is portrayed more matter-of-fact. The lyrical passages were especially hard to put into English, with long, sweeping sentences full of poetic descriptions and multiple adjectives. English is not as flexible as Portuguese; it prefers to do one thing at a time, and in a particular order. For the good of the text and to replicate the bounce of the original, the occasional adjective had to be sacrificed.

Then there was the magic: unexplained things are part of the fabric of a place like Serrano, but it can be hard for the poor translator to know for sure what’s happening. You look up words, of course, and double-check meanings, but it takes a leap of faith to decide that the rocks in the river really do change shape from one day to the next. You haven’t just misunderstood an unusual usage.

When I asked Salústio about the rocks, she picked up my Portuguese copy of the book to remind herself of the passage and then laughed. “I was pretty mad myself when I wrote this!” she said.

So do I feel honored to have translated the first novel by a Cape Verdean woman to be published in English? Absolutely. As a milestone there may be as much to lament as to celebrate, but it’s always an honor to be entrusted with a writer’s words and a privilege to help a great work reach a wider audience. When those words speak for generations of forgotten women and the work represents an oft-forgotten country, the honor is greater still.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions