Much of Africa was struck with the sad news of the passing of former Zambian President and statesman Kenneth Kaunda. According to the BBC, Kaunda died on Thursday 17 June 2021, of pneumonia, after being admitted at a hospital in the capital city of Lusaka.

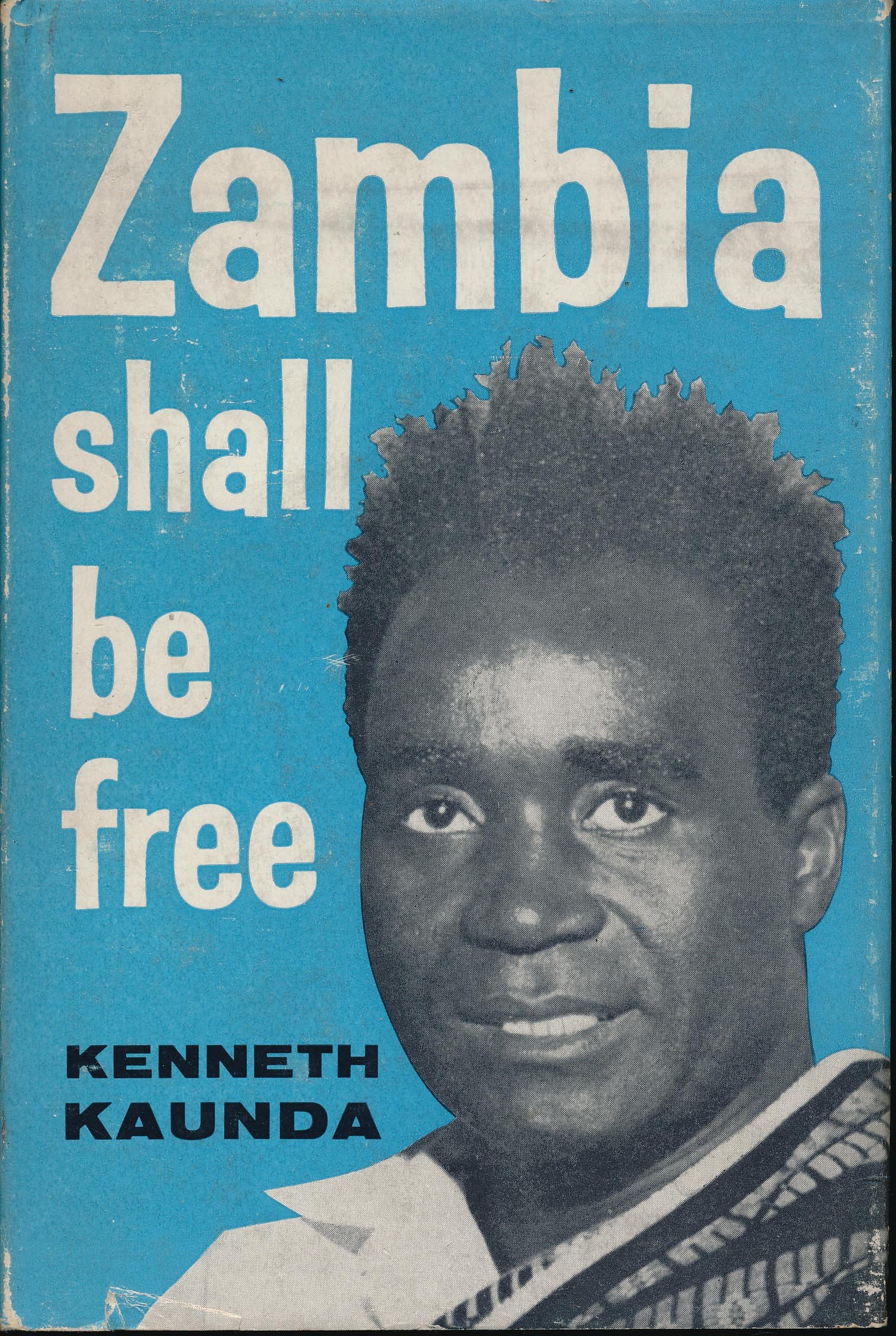

Before becoming Zambia’s first President, Kaunda was an activist fighting against colonial rule in what was then Northern Rhodesia. In fact, his political autobiography Zambia Shall Be Free was a pioneering decolonization text and one of the first set of works published by the African Writers series when it launched in 1962. The book outlines the trajectory of Kaunda’s own life and personal struggle while equally serving as a history text for Zambia, especially its struggle for political independence in the 1950s.

Zambia Shall Be Free runs the gamut of Kaunda’s experience in a conservative Christian household to his life as an anti-colonial activist. As such, the book gives us a portrait of the age of African resistance. The cultural arm of the decolonization struggle is often centered on literature, specifically fiction. Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi wa Thiongo and their peers first established a global literary platform for their anti-colonial writing in the 50s and 60s. But nonfiction was not always a part of this tradition. So Kaunda’s account of his life at the time was a much needed contributions to the growing body of literature exploring the widespread resistance against colonial rule. At a time when fiction dominated the African literary scene, Kaunda’s biography opened a new space for documenting the decolonization efforts.

Zambia Shall Be Free details Kaunda’s experience growing up in a Presbyterian mission, his large family, strict father, and supportive mother. Kaunda became a teacher thanks to his mother who saw him through school. Life in Northern Rhodesia was subjected to racist policies and colonial rule. Kaunda writes about his experience of racism. The biography gives insight into the experiences and influences that went into his political commitment, why he left teaching to join the resistance efforts. The biography not only provides insights into his admiration for Ghandi and Nkrumah but also details conflicts that defined local politics and the resistant movement.

He went on to publish other books, including A Humanist in Africa (Longman, 1966), Letters to My Children (Longman, 1973), and The Riddle of Violence (Harper & Row 1981).

Kaunda’s experience in coming up from humble conservative beginnings to heading revolutionary efforts to end colonial rule is really a biography of the larger struggle for decolonization. His work brought a lot of insight into the anti-colonial cause and complimented the growing body of writing on political philosophy and literary fiction exposing the injustices in colonial rule and calling for end of imperialism.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions