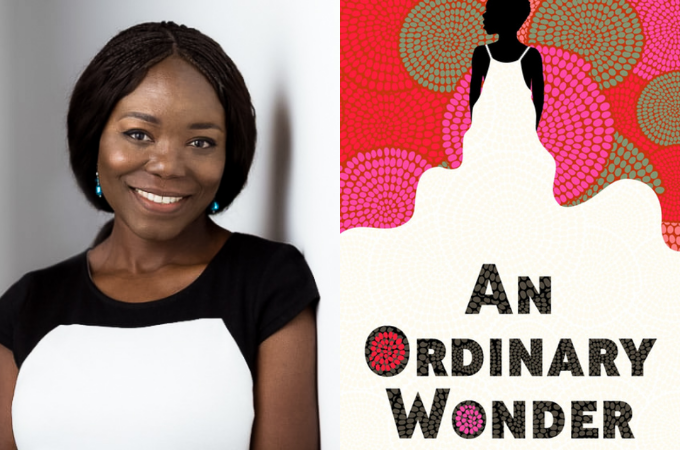

An Ordinary Wonder is the first Nigerian novel to center an intersex character. It tells the story of Otolorin, a girl who stands up against a world that refuses her humanity.

“My name is Otolorin. I’ve been called a monster” is how the story begins. Otolorin is born intersex to a Nigerian family living in Ibadan. Even though she insists that she is female, her family believes she is male and will stop at nothing to force her into that identity. Everything from physical abuse, psychological manipulation, religious intervention, to parental neglect. Thankfully, though, the story is powerfully affirming. The drama rides on Otolorin’s brutal experience with bigotry as much as it does on her relentless fight for survival.

Her misgendering is, however, not the only problem. In being intersex, people around her believes she has broken some kind of law of nature. They see her as not fully human, a perception that they use to justify various kinds of violence done to her. Papillon’s debut is a cautionary tale. Society becomes monstrous when it makes monsters of its own children. Papillon shows us the violence that is possible in a world that limits sexual/gender identity. “You are not a girl, Otolorin. You are a boy,” her mother replies the first time Otolorin declares her femininity. “And if you ever repeat those words or let anyone see your privates, I’ll lock you outside at night for gbomo-gbomo to steal.” At the time, she is only five years old. At 12, she is thrown down the stairs by her mother for wearing a dress. Nowhere is safe for Otolorin, not the church, school, or the family.

An Ordinary Wonder was a difficult book to read. It sat on my desk for a while before I picked it up. I was 7 months postpartum at the time and suspected that it might be a difficult read. Something about nursing an infant made me particularly sensitive to children being hurt. I just couldn’t imagine the thought of a mother who could wish her child dead. Moji does a lot for the story. A good bit of the tension in the story revolves around her refusal to see, love, or care for Otolorin. She embodies the intimate manifestation of bigotry. Sometimes, the people we are closest to find it the hardest to see our humanity. She also embodies the fear and anxiety that society feels for individuals it casts out as threatening to its cookie-cutter reality. But, for all her evil machinations, Moji is never caricatured. Papillon gives her ample space to grow. As the story moves along, it becomes clear that Moji was not born a villain. And though this fact does not justify her treatment of Otolorin, it is important that Papillon is able to show that both Moji and Otolorin are betrayed by a system where your worth as a human is tied to your sex and gender, where fact of being born a particular way extends privileges that are denied someone born a different way.

The arc of Otolorin’s story bends her journey to self-discovery, a process that involves her finding love and friendships. These people give her the language she needs to validate her existence. One of the first places where Otolorin finds safety and recognition is at the shrine of an Ifa priest. The Babalawo says that as far as the gods are concerned, she is a girl: “while she does embody aspects of the cosmic gourd enfolding both male and female facets of life, her stone whisphered that the form which best favours her destiny in this life time is female.” This is one of the most beautiful moments for me because it shows how to lean into African cosmologies to expand our ideas about different ways of being. We need to acknowledge the powerful decolonial gesture of Papillon situating indigenous Yoruba knowledge as a space where sexual identity is understood with complexity. Even though indigenous African worlds are not perfect, they have always been open to non-binary ways of looking at the world.

As far as literary characters go, Otolorin is beautifully made. Along with Azaro in Ben Okri’s The Famished Road and Kambili in Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus, Otolorin is one of the great child/youth characters that command a story with their endearing presence mixed with ancient wisdom. Her voice is clear and resonant. She is open about her abuse and her struggle with shame but not so that you pity her. Her suffering draws you into the story but what keeps you is the complexity of her being, how she straddles multiple worlds, some of which are magical. Her world is molded from cosmological, mythological, poetic/artistic, and scientific elements. It is richly layered and binary-defying. An Ordinary Wonder is gripping, not just because the twists and turns are plentiful but also because the world-building is immersive.

Some stories are designed to delight us, others to shift our frame reference so that we can see the world more justly with kindness and deep understanding. An Ordinary Wonder is both. It gives us the language to interrogate the deep-seated prejudices about gender and sexuality that define our world and the laws that justify them. But it is also gripping story about love always winning.

*************

AsepaOrele February 02, 2022 08:16

Excuse for that I interfere … I understand this question. Write here or in PM. http://191.downloadfirstyou.com/