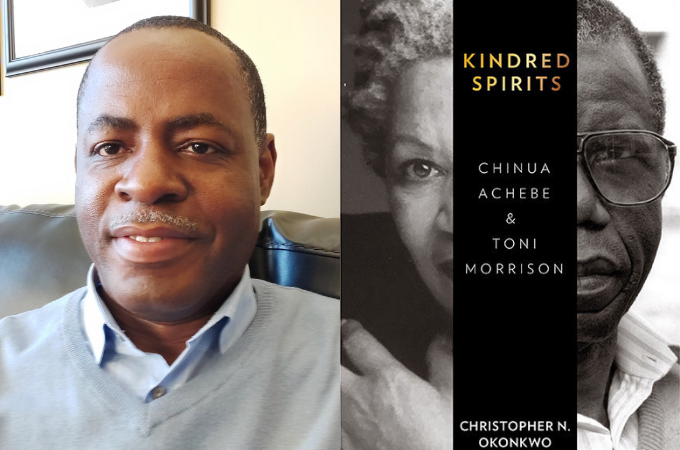

In celebration of Black History Month, we are asking our readers to give some attention to transnational connections between African and African American authors. Yesterday, we featured the two-man play in which South African author Siphiwo Malala re-imagines the life long friendship between Langston Hughes and Bloke Modisane. Today, we are presenting an interview with Dr. Christopher N. Okonkwo, author of the new book Kindred Spirits: Chinua Achebe and Toni Morrison published by the University of Virginia Press.

Kindred Spirits explores the personal and literary connections between famed authors Chinua Achebe and Toni Morrison. It is the first book-length study of Achebe and Morrison’s work. The book discusses their mutual respect and admiration for each other, proposes a theoretical framework for thinking through connecting threads in their work, and also compares their trilogies: Things Fall Apart, Arrow of God, and No Longer at Ease, with Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise. US-based Nigerian academic Chielozona Eze, author of Justice and Human Rights in the African Imagination: We, Too, Are Humans, remarks that Kindred Spirits is timely work and praises it for bringing African literature in conversation with Diaspora studies.

Christopher N. Okonkwo is an associate professor of English and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia. He has published in several journals, including Callaloo, Research in African Literatures, CLA Journal, African American Review, African Literature Today, and MELUS.

A quick note on Black History Month for those who might be unfamiliar with it. Black History Month originated in the United States. It is a month-long celebration and remembrance of the history, contributions, and successes of African Americans. What has become a nation-wide celebration grew out of Carter G. Woodson’s Negro History Week, in 1915. Since 1976, the U.S. government has acknowledged the month of February as Black History Month, and the celebration has now extended to other countries around the world, including Canada, the United Kingdom, and Ireland, though some choose other months besides February in their observances.

Enjoy the interview below and be sure to check out our dive into the book next week with a book feature on Dr. Okonkwo’s Work.

***

Brittle Paper

Congratulations on the publication of Kindred Spirits! What inspired the project?

Christopher N. Okonkwo

Thank you. Well, besides the unquantifiable respect and gratitude that I and millions of readers around the world have for Achebe and Morrison, the study is also the result of my attempt to tackle two pesky questions. One is what I flagged in the study as “African literature” and “Chinua Achebe” gaps in Toni Morrison studies. The second question, imbricated in the first, is my bewilderment that there had been no book-length comparative study, or a monograph of any kind, focused on both writers together. Not even an edition, or half the volume, of any of the numerous and widely circulating academic journals is devoted to them comparatively. Let’s not even talk about the yearly professional conferences. This was mystifying to me the more I thought about it, especially because the connections between Achebe and Morrison are so vast and seemed to me, at least, to be in plain sight. I also imagine that, viewed from the angles of literary canons, literary traditions, as well as race, their relation has disciplinary and black Atlantic implications. In any case, with all its typical book-imperfections—in content, analysis, editing, etc.—Kindred Spirits is my small intervention, my modest attempt to help fill those big gaps. I am hoping that I was able to bring one or two fresh perspectives on both authors’ critically acclaimed works. I recently described Kindred Spirits elsewhere as a book I wrote for myself. It’s the book that I long longed for, but which was not available, so I tried to write it.

Brittle Paper

Morrison and Achebe are both beloved writers with enormous global readership. What do we gain from seeing their lives, writing, and impact in relation?

Christopher N. Okonkwo

A lot, as I hope I demonstrated in the book. Even though Achebe and Morrison have joined the ancestors, they are, and for the foreseeable future will remain, in my book, two of the biggest names and draws in global black literatures. Other than what I identified in the book as striking parallels in both novelists’ personal and professional backgrounds, aesthetic visions, practices of art, and life philosophies, there are also the issues of black Atlantic history in general, slavery in particular, and African and African American relations that are inescapably forced to the foreground by any attempt to juxtapose both authors and their works. Nonetheless, one of the things we learn, as Achebe made a point to remind us, is that although black people’s stories are so dispersed geographically and may sometimes seem dissimilar in context, content, and crafting, they are, to use his words, “basically the same story.” I try to uncover those profound historical, thematic, character, and formal intersections in my pairing of Achebe’s and Morrison’s respective trilogies. For instance: the idea that Things Fall Apart is as much a (transatlantic and domestic) slavery novel as it is about imperialism and colonization; that there are commonalities between the characters Okonkwo, Nwoye and Ikemefuna and Beloved’s Sethe and her daughter Denver; that Morrison’s Jazz and Achebe’s No Longer at Ease are, respectively, about the New Negro and Jazz Age and the New African/New Nigerian movement and the Jazz Age in Nigeria. Or that Arrow of God’s nine-village federation “Umuaro” can be seen as an “all-Black town,” a paradise, a haven, the promised land, one compelled by the transatlantic slave trade and local slavery. And, like Arrow of God’s chief priest Ezeulu, the Ruby tyrants and murderers in Morrison’s Paradise see themselves as Arrows of God, as God’s (ap)pointed instruments to penalize and sacrifice the allegedly evil, Convent women. I still find myself marveling sometimes at the scope and richness of the works’ correspondences.

Brittle Paper

You aren’t new to the publishing world, your first book, A Spirit of Dialogue: Incarnations of Ogbañje, the Born-to-Die, in African American Literature came out in 2008. The book makes connections between African American literature and West African myths/folklore. Could you talk a bit more about that study if there were any shared connections from that book to Kindred Spirits?

Christopher N. Okonkwo

Sure. There are intentional connections between both studies. My research and teaching straddle African and African diaspora literatures and histories, specifically (twentieth and twenty-first century) African and African American literary, intellectual, and cultural productions. So, as a comparatist, my work is largely intersectional and interdisciplinary. Just the other day, an eagle-eyed friend of mine spotted my titular word play. He noted correctly that both books’ titles are semantically associated. I am invested in dialogue, and equally in the spirit of it; in short, in the conversations of Africa and the diaspora. Perhaps there’s something cultural and cosmologic, something deeply Igbo and egalitarian, or maybe it’s something from my being a middle child, that is divulged in my preoccupation with medians and sites of exchange. In the first book, I examined the multi-level, dialogical adaptations of the “ogbanje” and “abiku” experiences and mythic tropes by African American novelists, primarily Octavia Butler, Tananarive Due, John Edgar Wideman, and Morrison. I also speculated on the various historical, cultural, artistic, and philosophical reasons behind those narrative reconstructions of the spirit-child idea. You can say that the first and second books are siblings.

Brittle Paper

Can you talk more about the title? The word “kindred” evokes kinship. I find it fascinating to think of literary and intellectual relationships in terms of kinship.

Christopher N. Okonkwo

You’re right about the evocation. If we put aside for a moment the anthropological sense of “kinship,” the word, with its prefix “kin,” presupposes (inter)connections, complementation, continuity, etc. Kinship exists, and can exist, in the domains of literature and philosophy, especially, sometimes, literary and intellectual activities that are forged, not particularly by skin pigmentation, but rather by the same or related historical and cultural pressures. I believe that is what Ralph Ellison was suggesting when, in his essay “The World and the Jug,” he talks about the “sharing,” by a group, of a “concord of sensibilities.” However, my employment of the word “kinship” in the new book is not anthropological, but largely pronominal and adjectival.

Brittle Paper

You state that Kindred Spirits is the only book length comparative project dedicated to the work of Achebe and Morrison. What was it like realizing that no one had tapped into this topic and why do you think their connection is so under-studied?

Christopher N. Okonkwo

As far as I know, it is. There’s a book on Achebe and James Baldwin, Mr. Baldwin, I Presume: James Baldwin-Chinua Achebe: A Meeting of the Minds, by the late scholar Ernest A. Champion. It was published in 1995. Also, as far as I know, Champion’s study is the only other book on Achebe and another author, or black author specifically, from the Western hemisphere. It’s not that no one has tapped into the topic, as such. Achebe and Morrison scholars, and also general critics of African, African American, American and postcolonial literature, have variously noted both authors’ friendship, influences, and literary ties. Also, there was a historic dialogue between Achebe and Morrison organized in 2001 by Bard College president Leon Botstein. What hasn’t been done, however, is a rigorous, theoretically grounded comparative book on both novelists. As I stated elsewhere, in the several years that I worked on Kindred Spirits, and up the moment I received my copies of the finished book from the University of Virginia press, I lived with this fear that I’d wake up one morning and find out that someone just published a book on both authors. Achebe himself was convinced that another novelist could very easily have written a Things Fall Apart before him, because the core story that the novel tells was in plain sight. It existed everywhere in colonial Africa. Given how substantial and glaring I felt the Achebe-Morrison connections are, and the fact that both authors had been pointing us to the multiple areas of their comparability, I am still incredulous that another scholar didn’t produce the study way before I did. But having completed Kindred Spirits, I can see why the two writers’ relations have been understudied. The reasons may have to do with the kinds of challenge a book like this poses or would pose to a scholar. As folks in the field know, comparative studies, while exciting, are also exacting by nature. And, it’s Achebe and Morrison, their extensive canons and the voluminous scholarship on them that we’re talking about. So, there’s the anxiety of where to begin, point of departure, what to cohere, and of getting it all right, because of the focal novelists and the study’s potential seminality. The other is how deeply the critic has to know not just about the two writers and their worlds and works, but the various fields and literary traditions with which the two authors are associated.

Brittle Paper

In your book you mention the “irresolvable kinship questions and tensions —the family quarrels, so to speak—between both groups: Africans and African Americans” this book engages in. Can you elaborate more on these “tensions” and “family quarrels?”

Christopher N. Okonkwo

What I call the “family quarrels” between both groups are a consequence of the experiences, memories, and afterlives of the transatlantic slave trade and Africans’ direct involvement in that horror. They stem, too, from colonization and from unrelenting global migrations in which, with respect to the U.S. and the far-Right’s nationalism and populism, African immigrants and their descendants are lumped with others in the categories of resented “foreigners” and “aliens” competing with and allegedly displacing real Americans in various walks of life. In one of my essays, I dub the tension “You did me wrong,” “You did me wrong, too” dynamic. Although I don’t see a satisfying resolution to that “quarrel” anytime soon, it’s crucial that both groups not overlook or minimize their mutual enemy—racism and white supremacy.

Brittle Paper

Since I encountered your book, I have been thinking a lot about Black History Month and transnational connections. It seems to me that for some Africans, the celebration of Black History month is a more “African American” thing and not necessarily related to African culture/literature. What are the stakes, if any, in making Black History month less a Diaspora-centered celebration and more of a global black concern?

Christopher N. Okonkwo

I suppose the way that Black History Month is promoted as a Black American History Month in part accounts for the reactions m some Africans that you noted. Whether in politics, the media, schools, and other sociocultural spaces and discourses, much of what is celebrated is African American history, without which American history is woefully incomplete. None of the ongoing, politically motivated but grossly misguided attacks on Critical Race Theory, or the effort to ban Morrison’s Beloved in Virginia, will change that fact. Nor can it end the viewing and (re)telling of America’s history, or any people’s history, for that matter, from multiple and varying perspectives. Although many Africans may not directly see themselves in that celebration that began with the esteemed historian Carter G. Woodson’s more concerted effort in the mid-twenties to kickstart the commemoration, they are connected to it by the centripetal forces of modern black/African history and past that track back (to)ward the fifteenth century. With slightly over two million sub-Saharan African immigrants now residing in and contributing immeasurably to the U.S., and with hundreds of thousands of them and their African-American children holding American citizenships and being directly affected by anything that happens here, including presently the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on black people and communities of color in general, Black History Month is unquestionably their and American history. African American culture/literature is theirs also, and vice versa. We don’t often couch the celebration and its attendant discourse in this way. But if by making Black History Month a global black concern you mean black people, globally, adopting the February date, that’s completely unnecessary. February was designated because of its ties to Abraham Lincoln’s and Frederick Douglass’s birthdays. Any such move would again stir suspicions and concerns over U.S. dominance. Black people across the world, whatever their nation, celebrate and should celebrate themselves every day, each month, and not just in shortish February.

Brittle Paper

I was really interested in your discussion of Morrison’s work as an editor and publishing African literary work. Could you talk more about this mutual respect and support African and African American literary figures have had/have?

Christopher N. Okonkwo

As an editor at Random House for many years, Morrison published African authors and works, among the several works she edited. She was determined to gain a space in the U.S. education system for African literature. I don’t know if this is true: I heard that she even made efforts to recruit and publish Achebe under the Random House imprint. In addition to her friendship with Achebe, Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, and Ousmane Sembéne of Senegal, several African and African diaspora writers have credited her personal and professional assistance, as well as the influence of her works and ideas, in their writing careers. But the history of transatlantic collaboration, of mutual respect and support, among African diasporic and African political figures, intellectuals, culture workers, and students is hardly new, as the Pan- and pan-African movements illustrate. It goes back several decades and generations. I touch on it in the book, especially with respect to modern South African intellectual history, as well as the meetings and friendship of Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, W.E.B. Du Bois and, for instance, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Nigeria’s governor general at independence who had traveled to the U.S. in the mid-1920s for education.

Brittle Paper

African and African American literature is flourishing! A variety of African and African American authors have reached notable achievements across the globe over the past years. Are there any contemporary African and African American authors you could see as well connected that the public hasn’t paid much attention to?

Christopher N. Okonkwo

Without question, those two cousin literatures have experienced tremendous booms over the past years. In the case of African literature, all one has to do to begin grasping the extent and variety of that flourish is visit this beautifully named, online platform Brittle Paper. Readers, critics, teachers and all lovers of African literature owe Brittle Paper’s founder and editor, Dr. Ainehi Edoro-Glines, a debt of gratitude for establishing this amazing website that keeps us abreast of developments in global African literature but also, more important, champions entertaining yet insightful approaches to literary discourse. But going back to your question: yes, there are many contemporary African and African American, Afro-Caribbean and Black British authors whose works could be read relationally. I am teaching Jesmyn Ward’s canon this semester and planning a comparative essay on her work and that of a contemporary African female writer. We must not forget, however, the immense importance of critiquing works of African literature relationally. I encourage and invite critics to that pursuit.

Brittle Paper

Getting a book published is such a monumental task, so I hope you are planning for a deserved break after! I know it may be a while off, but is there a new topic of interest for another piece of writing/book you’re excited about?

Christopher N. Okonkwo

Yes. As I mentioned elsewhere, I am taking a moment to enjoy Kindred Spirits’ official entry—on February 15, 2022—into the world, particularly propitiously during Black History Month. After that, I get back to work on small and longer projects that I put aside to complete the book.

Brittle Paper

Thank you Chris for taking the time to chat with us about Kindred Spirits.

****************

Again, if you are interested for more details about the book, stay tuned for our book feature next week!

Okey Ndibe March 02, 2022 21:53

This is a rich feast of an interview! Okonkwo’s challenge, that literary scholars read relationally, is particularly resonant. As one who profited from Okonkwo’s first, extraordinarily illuminating work of critical scholarship, I can’t wait to read this, his latest. Congrats, Chris, and a debt of gratitude to Brittle Paper for highlighting the author and his work.