As Valentine’s day approaches, the literary world has its mind on love and romance. What is likely not at the top of mind for many readers is African love stories. This exclusion of African literature from the empire of love has everything to do with the common belief that African literature is too political for the frivolities of love. In his brilliant collection of love poems, Frank M. Chipasula laments this assumption, shared by both scholars and readers, which he sees as “reckless and dismissive.” His book, a compilation of poetry drawn from early modern Swahili literature, Malagasy oral literature, modernist writing of the 20th century, and more is a decisive response to this misconception. What, though, of fiction?

Since the inception of the African novel in the early 20th century, there have always been love stories or, at least, novels with strong romantic themes. The reason we’ve missed them is that love in African fiction has always been tragic. Tragedy as a literary form captures the realization that forces out our control are always moving us towards misfortune. Living under the brutal force of colonial powers had to have made African writers of the time feel a sense of tragic wonder about their world. They had no say or power to change the grand wheels of history changing every aspect of their lives. In some cases, love provided the language to convey the excesses of colonial violence. Thomas Mofolo’s Chaka was drafted before 1910 but published in 1925. Mofolo used the story of Chaka’s rise to power to channel contemporary anxieties around the extreme forms of violence inherent to any kind of imperial power, including that of the British. In one of the most moving scenes in the novel, Chaka kills the beautiful Noliwa, his long-time lover, hoping her death would bring him the ultimate kingly power. Noliwa’s death models for readers the ultimate betrayal that happens when power becomes too big to see people as humans and not simply pieces in the game of thrones. A. C. Jordan’s IsiXhosa novel The Wrath of the Ancestor (1940) features a doomed romance that ends in the protagonist’s suicide and failure to be the longed-for political messiah. Something about star-crossed lovers offered a powerful picture for conveying the tragic airlessness of colonial occupation.

The rest of the century plodded along in a somewhat similar fashion. In her defense of love stories, Ama Ata Aidoo places love on par with politics and religion as the dominant domains of existence. As a result, love cannot be decoupled from other areas of life. To do otherwise would lead to “a silly image of love,” which she attributes to romance fiction of the Mills and Boon and the Harlequin kind. When you separate love from the larger forces shaping life, you run the risk of pandering to existing expectations about gender norms, socializing girls into playing house while boys are heralded with stories about adventure and leadership. She contrasts this way of representing love with what she calls “serious” love stories. Because love does not happen in a social and political vacuum, stories about love should account for the social and political “consequences of love.” The love stories of the mid-to-late 20th century are mixes of tragedy and cynicism as writers burdened the romance plot with struggles relating to economic instability, political conflict, gender inequality, racial discrimination, and various forms of constraints in postcolonial life.

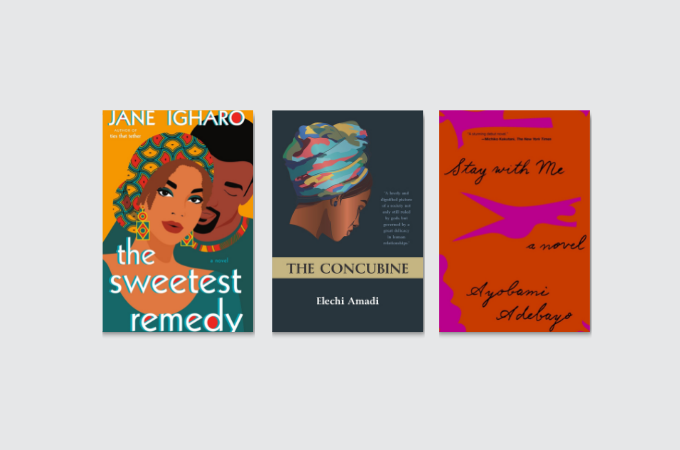

Aidoo’s Changes: A love Story (1991) is a classic example of a “serious” love story. It portrays the frustrations of a woman seeking love in a patriarchal world. So Long a Letter (1979) links the failures of the postcolonial state and the persistence of patriarchal rule to her characters romantic betrayal. We see women who love but are betrayed by a system where a woman is punished for desiring. There is also Joys of Motherhood (1979), Lewis Nkosi Mating Birds (1983), and Elechi Amadi’s The Concubine (1966). These stories all contain tragic elements that convey deep concerns over systemic forms of power in the aftermaths of colonial rule. We see this tradition of “serious” love stories continuing today in novels such as Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay with Me (2017) and Noor Naga’s If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English (2022).

The rise of genre fiction in African literature has opened up space for a new kind of romance fiction. Like their science fiction counterparts, African romance fiction writers are exploring the utopian possibilities in genres that are designed to have happy endings. These writers are moving away from tragedy as the dominant framework for the romantic imagination. They are less cynical and more open to exploring the possibility of love as a space for critiquing and overcoming big social problems. Cassava Republic launched Ankara Press as a feminist answer to the classic romance fiction and its reinforcement of gender norms and expectations. Yinka, Where is Your Huzband (2022) and Jane Igharo’s novels fall under this category of romance novels pushing the boundaries on what the genre offers. The space of romance fiction has grown rapidly in the last few years and expanded to include varied takes on what love is. Love Africa Press caters to the erotica audience and, in so doing, celebrates representations of African women exploring sex and desire. In Adrienne Yabouza’s Co-wives, Co-widows, the first Central African novel to be translated into English, love is polygamous. Yobouza’s depiction of Ndongo Passy and Grekpoubou’s thoughtful and sexually fulfilling relationship with their husband Lidou expands our vision of what forms love can take. One area where exploring love for its utopian possibilities has paid off tremendously is in the sphere of queer love. In some parts of Africa, homosexuality is considered illegal, but this has not stopped writers from depicting queer love. Emezi’s You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty, Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Trees, and the anthology Exhale: Queer African Erotic Fiction celebrate queer love while addressing the issues queer communities face.

Literature is the space where writers have the license to imagine an ideal love, the utopian experience of love, love as something that both exposes and transcends oppressive power and various forms of hardship. The big shift in love stories within the last 100 years of African fiction is the redefinition of what counts as truth in fiction. Showing how characters are crushed by the system is one way to reveal how systems work and critique them. But that is not the only way. Showing how systems are overcome is also another way of exposing how they work and critiquing them.

Further Reading:

39 African Romance Fiction, Love Stories, and Erotica

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions