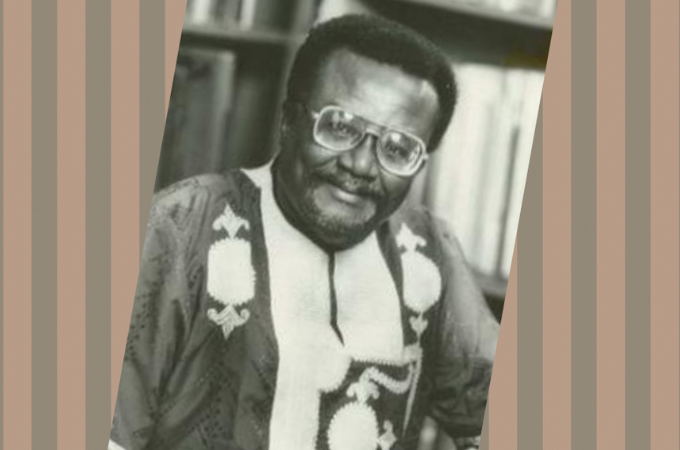

For so long, there have been numerous jaw-dropping stories about Ola Rotimi as a fastidious teacher, taskmaster and theatre visionary. All these myths and legends of the man coalesced on April 30, 2021 when Professor Niyi Coker hosted a webinar titled, “Remembering the Ori Olokun Theatre Legacy” out of San Diego State University. The inimitable Jahman Anikulapo, who prefers to be referred to as a culture activist but who in fact made his name as a journalist specialising in the arts, moderated the event with his usual mix of sly earnestness and brazen mischief.

Rotimi who passed in 2000 was indeed a major cultural leader at several levels and his life, background and accomplishments reflect the bewildering complexity of his native Nigeria. His father was Yoruba and his mother Ijaw. He spoke several languages and the tentacles of his legendary work can be felt in all corners of the world, around West Africa, Europe, the United States and the Caribbean. In each of those places, his devotees can be found proclaiming the gospel of his artistic significance and accomplishments. His most impactful work was done when he served as a professor of theatre arts at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife (then called University of Ife). He left Ile Ife in 1977 and transferred his services to the University of Port Harcourt. Allegations have been peddled that he decamped to Port Harcourt due to irreconcilable clashes with the formidable Wole Soyinka. Those allegations were not confirmed during the Coker hosted webinar.

Ola Rotimi is renowned for plays such as Our Husband Has Gone Mad Again, Kurunmi, The Gods Are Not to Blame, Ovonramwen Nogbaisi and many others that have since become staples of modern Nigerian and indeed West African theatre. He is also noted to have established one of the most innovative theatre collectives ever established in West Africa, the Ori Olokun theatre group. By most accounts, Rotimi was an inspirational teacher, identifying latent talent, nurturing and developing it, and generally creating an atmosphere where budding creatives can find their voices. Many actors who worked with him over fifty years ago testified that their experiences with him changed their lives. They learnt the virtues of rigour, discipline and commitment. One of the actresses who worked at his drama company but now functions as a nurse in Manchester particularly stressed how these attributes continued to inform their lives in their respective corners of the world.

Another innovative aspect of Rotimi’s work was the manner in which he bridged the divide between town and ivory tower. He painstakingly selected a creative mix of professional thespians and amateurs drawn across the gulf between varsity and, in the case of Ile Ife, village. This approach lent his dramaturgy rare energy and breath of life whereas other strictly university-based theatre productions tended to be stifled by excessive pedantry.

Rotimi did for dramatic language what Chinua Achebe did with English in the African novel. Just as Achebe had done, Rotimi was able to unfetter the language from its Eurocentric moorings so it could waltz and travel with native rhythms across local landscapes picking gradations that resonate with our histories, stories and most hidden aspirations. In this manner, English was no longer just plainly English but had become Yorubanglish, a dialect that Rotimi undoubtedly excelled better than another purveyor of the form, the novelist Amos Tutuola. Since then, Yorubanglish has flourished culminating in the remarkable achievement of Toyin Falola in his inimitable memoir, Mouth Sweeter than Salt. Omofalabo Ajayi-Soyinka, emerita professor of dance and drama at the University of Kansas highlighted the liberation Rotimi bestowed on the English language struggling within a postcolonial context.

Ideologically and conceptually, Rotimi, a product of Boston University and the Yale School of Drama, faced the dilemmas of decoloniality, that is, discovering an autochthonous voice as a counter-hegemonic presence against Euro-American modernity. It was a dilemma the great African American dancer and choreographer, Katherine Dunham faced in re-discovering the complex and layered worlds of black dance in a Eurocentric milieu of absolute epistemic and aesthetic refusal; that Chinua Achebe ran into when he sought to recuperate that which was lost in colonialist violence; and that which Rotimi and his colleagues at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ife, battled with as they fought to forge creative identities that were aligned with their communal histories and experiences against an intimidating backdrop imposed by the hegemonic Greco-Roman paradigm. Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex provided the initial impetus which spurred Rotimi to create his landmark play, The Gods Are Not to Blame, and which in turn refashions classical Greek drama in a way that reflects local cultural mores, linguistic inflexions and cadences and finally, local cosmological realities.

Duro Oni, venerable drama technician and professor of cultural studies at the University of Lagos, marvelled at Rotimi’s uncanny skills at marshalling and choreographing large crowds, something that was more common with great modernist filmmakers such as David Lean and Akira Kurosawa. But rather than having the liberty to do so outdoors like film directors, Rotimi had to perform his intricately plotted orchestrations within the crammed confines of a theatre. According to witnesses, Rotimi’s productions hardly experienced any hitches because he charted them meticulously so that even when actors had to move in total darkness they did so without bumping into one another. In this respect, many theatre insiders attest that his skills were superior to Soyinka’s.

According to numerous accounts, Rotimi is by far the best theatre director of his generation and this is clearly evident through the esteem in which he is held by those who have worked with him. From the sheer number of theatre heavyweights present at the webinar, it is indisputable that Rotimi elevated and transformed minds. The roll call of attendees is almost mind-boggling; an evidently delighted Funso Aiyejina of the University of West Indies, Jimi Solanke, legendary fixture of modern Nigerian theatre, television and film, Chinyere Okafor of Wichita State University, Diedre Badejo, an American professor of African literatures, Peter Badejo M.B.E., internationally renowned award-winning dancer and choreographer, Bode Sowande, playwright and professor of drama and Bose Ayeni-Tsevende, drama lecturer and actress. There were a number of others as well not mentioned here but they all unfailingly testified to their lives being transformed by their experiences working with Ola Rotimi.

Apart from Rotimi many other figures were mentioned frequently as being pivotal in shaping modern Nigerian theatre at Ife. Peggy Harper, a South African dancer and choreographer who passed in 2009, is credited as a pioneer of in her field. Bose Ayeni-Tsevende asserts that all modern approaches to traditional dance in Nigeria can be directly traced back to Harper methods, theories and practice. In addition to Rotimi, she also worked on Soyinka’s and John Pepper Clark’s dramatic productions. Solomon Wangboje, an artist influenced how the sets looked and were constructed. Akin Euba’s music compositions and elaborate teacher/student interactions were equally central in developing the concept and practice of complete theatre at Ife.

Indeed Rotimi is an invaluable lodestar in the firmament of West African dramatic arts. And a simple way of measuring his immense success is by noting the huge numbers of theatre practitioners who made their own significant names after having been trained by, or working with, him. Consequently, a pertinent African axiom is that you cannot be regarded as being successful at what you do until other people become successful through you. One thing that was evident is that Rotimi possessed immense passion for theatre and transferred it to those who were fortunate to work with him. Each participant spoke highly of the master as an exemplar and as an unstinting source of inspiration.

The experience of working at the Ile Ife based Ori Olokun theatre company provided the occasion to celebrate the university’s pedigree. Participants at the webinar gave off the impression that they were special due to their shared history and common experiences. It was also as expressed in a jovial way, a call to arms. Unquestionably, Ife has been significant in supplying the Nigerian art space with a steady pool of first-rate artists many of whom surfaced at the seminar such as Edmond Enaibe and others whose names were constantly mentioned such Olu Okekanye, the late Toun Oni and co.

As for measures to preserve and extend Ola Rotimi’s legacy, Professor Niyi Coker was assigned the task of writing the definitive biography of the late dramatist. Pledges were also made to institute an annual, or at least regular, Ola Rotimi international conferences and festivals. At the end of the event, re-invigorated by meeting old friends and colleagues after such a protracted absence, the loyal devotees of Rotimi looked as if they were only just starting as exhortations of “Great Ife” became louder and more frequent as things gradually wound down. But beyond all of this, the legacy of Rotimi and collaborators such as, Harper, needs to be inscribed deeper into public consciousness if only for the courage, dedication and selflessness with which they pursued their work.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions