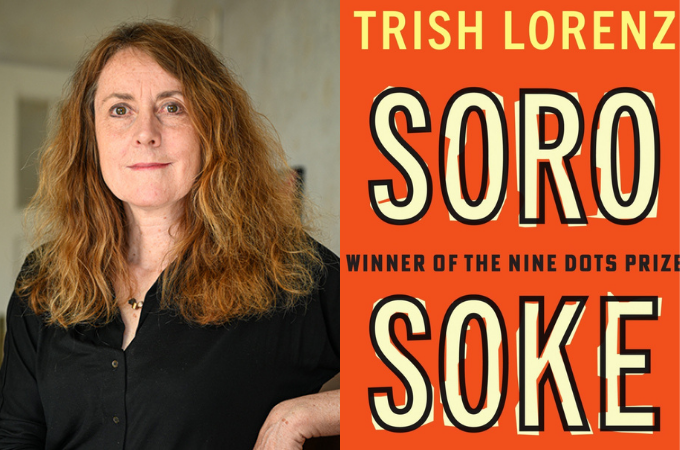

Social media has been abuzz about the new book by Berlin-based author Trish Lorenz titled Soro Soke: The Young Disruptors of an African Megacity. With almost 7500 signatures on a petition calling for a public apology by the author, as well as asking that the book be recalled, the book has sparked conversations around cultural appropriation and systemic issues in publishing.

About a year ago, Lorenz won the Nine Dots Prize. The prize is awarded to a book project that “tackles contemporary societal issues.” You enter the prize by responding to an assigned question in a 3000-word essay. Last year’s entrants were invited to responded to the question: “What does it mean to be young in an ageing world?” Lorenz presumably won the prize for an essay about how young people in Nigeria were disrupting the status quo. Winning the prize came with a $100,000 check and a book deal with Cambridge University Press.

The book, titled Soro Soke: The Young Disruptors of an African Megacity, was published on May 26th and features interviews with Nigerian creatives disrupting the status quo in diverse spaces, from art and identity, to feminism, homophobia, the diaspora, and entrepreneurship. Lorenz centers this narrative of disruption on the famous #EndSars protest, which also came to be associated with the Yoruba term sòrò sókè, meaning “speak out.” Lorenz uses the term in her title, centering the protest as an iconic expression of Nigeria’s revolutionary youth culture. The #EndSars protest was an unprecedented, awe-inspiring social movement by millions of young Nigerians in late 2020, demanding sweeping police reforms and better governance. It lasted a few weeks, culminating in the unfortunate loss of lives of dozens of Nigerians after members of the Nigerian military reportedly opened fire on protesters in Lekki, Lagos, an incident now dubbed “The Lekki Massacre.”

Up until the publication of the book, everything seemed fine. In fact, on the day of the publication, Lorenz tweeted: “I am so excited that my first book, Soro Soke, is published today. To see it advertised in the CUP bookstore windows is mind blowing. I can’t stop smiling.” But things quickly took a turn when a statement she made in an interview surfaced. The interview was published before the book’s launch, on May 18, and contains remarks that led people to think she was claiming to have invented the term “soro soke generation” as a description for young Nigerians who participated in the protest. She said: “this cohort exhibits a confident outspokenness and a tendency for creative disruption, leading me to name them the Soro Soke generation.” [The interview has since been updated accordingly.)

The statement immediately sparked outrage from many Nigerians on the grounds that the term “sòrò sókè” was in fact a Yoruba word that had emerged during the course of the protest, and not credited to Lorenz. Also, many questioned the accuracy and appropriateness of having Lorenz use the name for a book—as a white European author, not based on the continent.

These sentiments were expressed in a petition made by Nigerian researcher Tamkara O. Adun. The petition, which has almost 7500 signatures, points to the the cultural insensitivity of titling the book with a term that still holds painful memories for many Nigerians. Seeing that Lorenz won the $100,000 Nine Dots Award for the project, in addition to a publishing deal with Cambridge University Press, the petitioners questioned the ethics of what they saw as her “profit[ing] off the trauma of Nigerians.” The petition sees Lorenz’s book and her comments as reminiscent of colonialist exploitation, as well as raises questions about who gets to tell what story and gets access to support from the publishing industry. “This is a Nigerian story to tell,” writes the petitioners, “and we have Nigerians who are qualified to tell it. We have already told it without support or visibility. African stories must be told by African people.”

Some notable Nigerians weighed in and raised similar concerns. See below for comments made by CNN journalist Stephanie Busari; NLNG Prize-winning author Chika Unigwe; Bolu Babalola, author of Love in Colour, Ukamaka Olisakwe, author of Ogadinma, and Romeo Oriogun, author of Sacrament of Bodies, author and publisher Lola Shoneyin and writer Jennifer Chinenye Emelife. While Lorenz has not yet made a statement (at the time of publishing this article), Cambridge University and its collaborators on the project have made a statement. Also see below for their comments.

Stephanie Busari:

“To use ‘Soro Soke’ without framing it within #EndSars (I say this based on her interview about the book where there is no mention of this movement ) shows a profound lack of context. People died for their right to ‘Soro Soke’ (speak up) and it is THEY who deserve all the credit.”

To use 'Soro Soke' without framing it within #EndSars (I say this based on her interview about the book where there is no mention of this movement ) shows a profound lack of context. People died for their right to 'Soro Soke' (speak up) and it is THEY who deserve all the credit.

— Stephanie Busari (@StephanieBusari) May 30, 2022

Bolu Babalola:

“All I am going to say is that “Soro soke” means “speak up” in Yoruba and was a mantra for Nigerian youth during the protests and it is interesting which voice is behind this book lol”

https://twitter.com/beebabs/status/1530622075295105024?s=21

Romeo Oriogun:

“Nigerians lost their lives & livelihood. People went on exile, people are still suffering. & you, a White woman from Europe, are claiming that you coined the phrase people defended till their deaths, a phrase that originated during the struggle. Are you not ashamed?”

Chika Unigwe:

“I wonder what kind of guts it takes to claim you coined a term in a language you probably don’t speak . #sorosoke #SoroSokeGeneration”

I wonder what kind of guts it takes to claim you coined a term in a language you probably don’t speak . #sorosoke #SoroSokeGeneration

— chika unigwe (@chikaunigwe) May 29, 2022

Nigerian author and publisher Lola Shoneyin called for channeling the outrage against Lorenz’ book towards constructive ends:

The most constructive way to channel the understandable anger is buying this book (that was published for the Nigerian market). Make it a national bestseller, then watch how our publishing industry responds to submissions that detail significant events. https://t.co/je7fLEfNAC pic.twitter.com/DGepsTWdSP

— Lọlá Shónẹ́yìn (@lolashoneyin) May 30, 2022

Shoneyin is referring to Sọ̀rọ̀sókè: An #Endsars Anthology, edited by Jumoke Verissimo and James Yéku, featuring exceptionally talented Nigerian poets and originally published here on Brittle Paper. Nigerian writer Jennifer Chinenye Emelife shared similar sentiments on Facebook:

If you’re so mad that a white person is trying to reap off your pain, BUY, READ, TALK, WRITE about our own title. Own your narrative, make it a national bestseller, so much that it overpowers that of this foreigner. We can’t continue to cry over things that are taken from us. We could channel those tears into building and sustaining ours. The West can copy all they want but let’s centre our own stories. How hard can it be?

Cambridge University Press, Nine Dot Prize, and the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities where the interview was published issued a joint statement on May 30 via twitter.

There was no intention by trish Lorenz, or anyone involved with teh book, to suggest that Trish invented the phrase “soro some generation,” and no such claim is made in the book. Rather, it was an unintentional turn of phrase in a single interview, the text of which has now been corrected. Soro Some was chosen as the title due to its use as a rallying cry and call for change among young protestors in Nigeria— something which is made clear in the book. — The Nine Dots Prize, Cambridge University Press and CRASSH

Cambridge University Press have also made the book free for download on their website. Read it here.

softbigs August 22, 2023 17:55

I'm interested in reading this book!