Mr Wole, the world stands under my trampling feet on this solemn day that fate has broken its barriers, which are like the sticks of the Illujinle masquerades who had backs that could not break. Somewhere, the voice of an old man would say, sumptuous meals are not eaten with a spoon. These words are what I must take to ears on this day that glistens with promise, for I have seen the old, ragged man who had the wisdom of a thousand Solomon’s put in order.

I have drummed your dancing words into my ears, whose beats sound like a distant trumpeting of the Sahara elephants. And if that unpopular sage that says ‘every naked foot must attain a bruise’ is true, then I believe that my open mind has gone far in attaining bruises from your grandiose use of expressions and imagery which in one accord comes from a long line of ancestral ingenuity merged with a well-grounded English experience. Your stories about Yoruba of the primitive times are surreal in its inclusion of street dancers, witty kings (Balewas), and partly educated teachers. All the ones who had the daring guts, of all things, to run after a girl in the open, while still claiming to have been dipped deep in the white’s man ways. I can rarely find modern teachers on record who have done such. Still, these impressions only prove your well-detailed knowledge of how much of a clown old schoolteachers were (and that’s an expanse to my research on the ways of the ancient teachers). I attribute this to your quintessential drama, The Lion and the Jewel. That piece was a stroke of genius.

Again Sir, if these words do not get weary of me saying them, how did your books manage to succeed in Africa? My peers complain about how boring and turgid your novels are. This again puts me out in my analogy of our forefathers’ brains with ours. Sincerely, I too found your novels too unappealing to my literary taste at first, except that I had a change of taste later. And left to me alone, I would not have spent a dime on your novels because why? Why would I settle for brain-cracking, turgid books when the beautiful and relatable debuts of Chinua Achebe and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie are still laying in bookshops and library shelves? Does it mean that those who bought your books then were wiser than me and the thousands of students who would widely open their untamed mouths to say, ‘I don’t understand any damn thing from that novel’? But no, I don’t expect an answer to this question because I know quite well that your literary hormones are naturally built up of academically grounded genes, plus, which writer does not even want to walk on a unique path?

I have an analogy that you were a bit of a gangster but in a more fashionable, less violent way. First, you were one of the first catalysts of a student group that campaigned for change at the University of Ibadan. No regular human would do that. It takes a bold, if not violent, person to stand against a Nigerian problem— a Nigerian one. Also, you were very active in criticizing every successive power in Nigeria during the 1900s. It landed you in trouble then you escaped via the Nadeco route, ON A MOTORCYCLE. In my hours of seeing Indian movies and reading crime fiction, I’m only meant to understand people who ride motorcycles are badass, dangerous people who are not easily joked with. Then, you once confessed openly that you smoked hard cigarettes. That’s true. But who should raise their tides on me if I dare make these expositions to make you look like a bad person?

I just don’t understand how you managed to have this war-style personality and still win a Nobel laureate. Because down here, the stereotypical person would expect me to be calm, simple, have a very good character, live a perfect life if I ever wanted or should ever dream of winning a regular school award, to start with. Here, people are blind to the results and are only keen on the details. What’s your take on this?

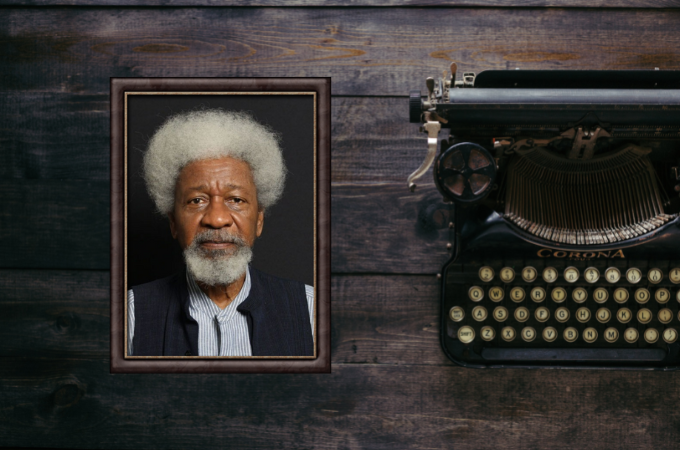

Finally, Sir, I like your hair. It looks like a mass of wool, the same that is used to clean my wounds. And that is just a miniature statement when it comes to your mode of dressing, most times you dress like a wealthy professor from the past. Still, I especially love the look on you. It somehow fits with the ancient flavour I find in your books. You have my admiration. You look like a different species of bird. Saying this, I imply the way you look in the pictures of African heroes I often see while passing a place in my town, called the CS Park. I just wish that like historic museums, we should also have a literary museum, where I can find endless displays, thousands of ancient and modern writers. Especially the ones I used to crush on, like Emily Bronte, who gave us a full view of her wild mind which is artistically displayed in Wuthering Heights but gave no idea of herself.

You did not only win a Nobel prize, Sir, you also won thousands of hearts by teaching us that good literature can shake the brain.

Photo by Patrick Fore on Unsplash

Sam Madeyin September 14, 2022 15:21

Blessed memories in confinement ideas of yours. Great writing pen!