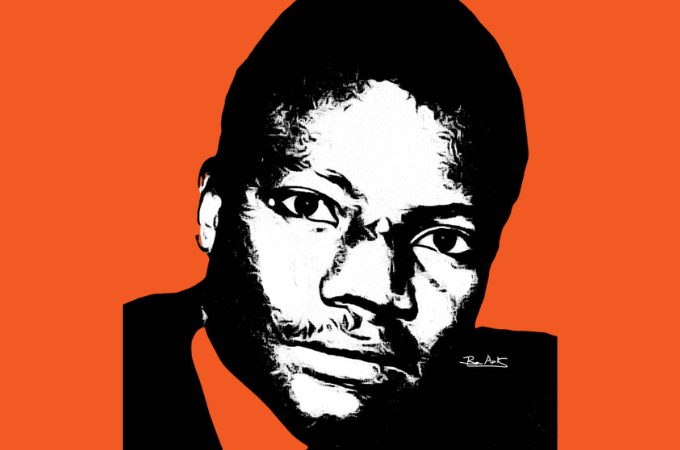

In an essay titled “A Malian Writer Finds a Postmortem Revival: How a French literary event in 2021 brought author Yambo Ouologuem back to life,” Paris-based journalist Olivia Snaije details the tale of Yambo Ouolouguem’s plagiarism controversy in 1972.

Ouologuem was born in the Dogon region of Mali to an affluent family. His father worked for the colonial government and could speak many languages. Ouologuem found success of his own at an early age when he published his first novel in France to critical acclaim when he was just 27. Titled Le Devoir du Violence, it tells the story of a fictional African empire ruled by corrupt leaders and rife with evil and violence. Ouologuem did not get to enjoy his success for too long. A year later, he was accused of plagiarism, a controversy that led to a cross-continental lawsuit, the banning of the book in France, and discontinued publication by other presses. Disillusioned, Ouologuem left France for Mali where he lived the rest of his life away from the public eye.

Snaije revisits this story, detailing Ouologuem’s rise to literary success, the plagiarism controversy, and recent attempts by his children to clear his name. She addresses the tensions between those who, at the time, believed that Ouologuem was guilty and deserved all the backlash versus those who believed that the situation was blown way out of proportion. The essay is brilliantly written layered with biographic details that truly bring Ouoluguem’s experiences to life and adds a human angle to a story that was clearly traumatizing for everyone involved.

Read the short excerpt below and follow this link to read the rest.

“A little more than a year after “Le devoir de violence” was published in English, accusations of plagiarism were leveled against Ouologuem. It began with a research student who spotted borrowings from one of Graham Greene’s books. Ouologuem’s British editor, James Currey, told New Lines, “Graham Greene found it annoying. It was a piddling little stupid thing. … I hope it doesn’t happen today; I hope we’ve grown up slightly. I had forgotten about this, but rereading my two and a half pages about the controversy [in Currey’s book “Africa Writes Back”], it was fundamentally a waste of time. I am as mystified now as I was at the time.”

Greene did not press charges and accepted the British publisher’s offer to include appropriate acknowledgment in future copies of the book. In the U.S., however, the chair of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich decided to withdraw and cancel all future publications of “Le devoir de violence.” Moreover, Harcourt demanded $10,000 in damages from Le Seuil. (According to the archives, Le Seuil later ended up paying about half of that sum to the U.S. publisher.) From then on, the affair blew up in the French media, where borrowings from a short story by Guy de Maupassant, a crime novel by John D. MacDonald, the Bible and the Quran were spotted.

In 1968, when Ouologuem’s editor wrote to Schwarz-Bart with a copy of Ouologuem’s book, Schwarz-Bart, who was also accused of plagiarism when “Le dernier des Justes” was published, wrote back that while he was troubled and hurt by the fact that his own publisher, Le Seuil, hadn’t seen fit to tell him earlier about Ouologuem’s reworkings of several passages from his book, he wrote: “I am in no way worried by the use that has been made of ‘Le dernier des Justes’ … I have always looked at my books as apple trees, happy that my apples will be eaten and happy if now and again one is taken and planted in different soil.”

At first, Le Seuil and Ouologuem attempted to defend themselves in the press. The author claimed that Le Seuil had removed quotation marks around the paragraphs in question and explained his “literary technique” of borrowing and reworking texts. Ultimately, Ouologuem was left to defend himself on his own. He was savaged in the French press, and his fall from grace was complete. It is said that he had gotten into a brawl and spent time in a psychiatric hospital, although no records of his stay have been confirmed. He then returned to Mali definitively, embittered and determined, never to have anything to do with France again. Family members speak of him arriving in Mali ill and say that he was poisoned in France. Soon after, Ouologuem turned toward religion, became a devout Muslim, and refused to speak of his time as a famous author. He also remarried and had three children.

Most academics now agree that the plagiarism charges against Ouologuem, which occupies a small percentage of his book, fall into what can be called a “gray area” as plenty of writers, including T.S. Eliot, Graham Swift and P.D. James, have used the same method of intertextuality. The damage to a brilliant young writer, however, was already done. In November 1982, according to Orban’s research, Le Seuil stopped publishing “Le devoir de violence.” Heinemann followed suit.” Read more.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions