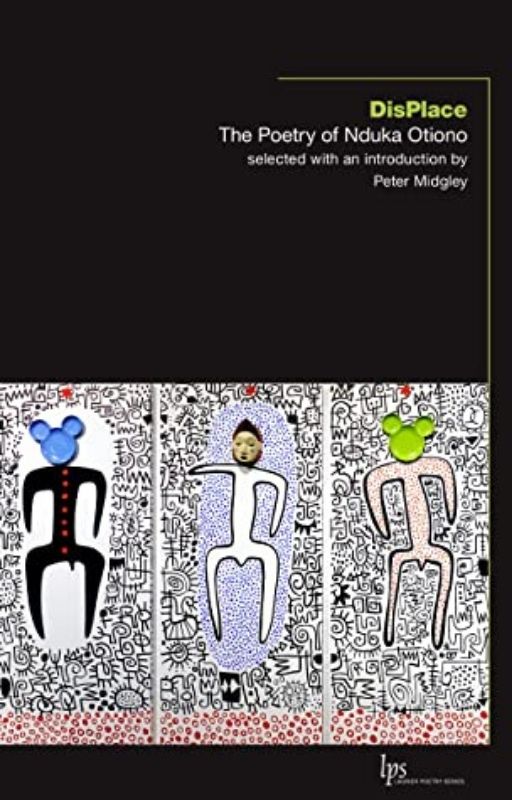

A Nigerian poet, literary scholar, and academic, Nduka Otiono is a phenomenal name in the world of African literature, and literature worldwide. A former General Secretary of the Association of Nigerian Authors and a member of the board of directors of the Canadian Authors Association, Otiono is the author of The Night Hides with a Knife, Voices in the Rainbow, and Love in a Time of Nightmares. In his 2021 collection of poems, DisPlace, Otiono documents the cyclic transition of history and the intransigence of tradition from where his memory of time and place originates.

Reading Otiono’s interview with Chris Dunton, which serves as an “Afterward” for the collection, one will realize that the poet embodies such complex ramifications of migration which complicate the idea of home. But what is surprising is the intrinsic skill with which he engages the mnemonics of distance, summing the diameter of home and exile into a lyric of nomadic negotiations. In the collection’s “Foreword,” Tanis MacDonald, the general editor for the Laurier Poetry Series, gives a brilliant but imperfect observation, which is that DisPlace provokes conversations that “challenge ideas about Canada and seek to illuminate and bring to consciousness better futures.” DisPlace enables Otiono to look back and forward on his Nigerian and Canadian heritages and to frame a convoluted identity out of the chaotic solitude of his hyphenated experience.

For instance, in “Today, Time is the Eyeglass I Wear,” Otiono undertakes the ritual of ancestral reconnection. In the process, he collapses time into timelessness, testifying that “time is the eyeglass I wear.” Since glasses enhance vision, readers may well see just how enlightening and significant time is to the poet in the performance of his sacred obligation. Also, Otiono implies that time lessens the burden of history. This is so because “The purple rim” of the eyeglass “masks the scars of the years” he has lived through. Readers of DisPlace who are aware that glasses shield the eyes against the sun may also imagine the traditional masking that crescendoes the ritual of regeneration the poet undertakes. Moreover, Otiono situates time firmly in its full spiritual element, inviting readers to participate in the eternal dialogue that takes place “at the altar of time,” where the “secrets of the Most High” reside.

There is a possibility to misread “Today” as Otiono’s fusion of his Christian and traditional African religious beliefs, as Peter Midgley does in his analysis of the poem in an otherwise stunning “Introduction” to the collection. In Midgley’s words, the poem demonstrates that “in Otiono’s world, Catholicism and animism become intertwined in the words and the structures of the poetry,” but this is not the case. “Today” carries the weight of Otiono’s absolute dedication to his African heritage, a deviation from the cultural and religious syncretism associated with postcolonial literature. By linking Otiono’s use of “Most High” to Christianity, Midgley misses the point of Otiono’s cultural milieu, for “Most High” is simply the English translation of the Igbo word “Chukwu,” the most esteemed god in the Igbo pantheon of deities. Otiono’s use of “Chukwu” and “Ikenga” is basically an effective appropriation of the resources of the English and the Igbo languages.

In “My Lips Bear Witness to the Blood that Irrigates my Heart,” Otiono laments about the viciousness of Covid-19 and the mysteries surrounding the pandemic. Covid-19 so flattened the world in 2020 that the possibility of a new year seemed almost impossible. This is what Otiono captures when he announces that “an aging winter declaims New Year resolutions dead on advent.” In “A Chain of Requiems,” Otiono returns to lay wreaths on the graveside of victims of the pandemic, while also denouncing the aridity of feelings that Covid-19 orchestrated in the world, because people “vanished without farewells” and were “buried hurriedly amidst silent funerals.”

In “Untangling Cobwebs in the Mind,” Otiono comes across, again, as a self-conscious artist weighing the compulsions of his primordial root against his Western influences. When the poet says, “in caverns of white light, I appropriate Virgil,” he speaks of his literary apprenticeship to the poet, Virgil. The “caverns” serve as Otiono’s vehicle into the West, which is fittingly described as “white light.” Indeed, Virgil could as well be read as a symbolic representation of the Western debts Otiono accumulates in his life’s journey, because, as the poet tells us, he is assaulted by memories of goodwill. In spite of this indebtedness to the West, Otiono reaffirms his spiritual belonging to his homeland when he announces, “I am son of Otiono, the champion wrestler.” Essentially, while Otiono’s displacement from Nigeria is only physical, his engagement with the literary and cultural traditions of the country and its people is absolute and infinite. It is significant that “Untangling” is followed by another personal poem with which Otiono furthers his self-search and documents his experiences in sonorous soliloquies. So, in “Dad,” the poet mourns his father, whose passing left him with only memories, because “time has swept the landscapes of [his] mind.”

In their citation, the jury of the Archibald Lampman Award that shortlisted Otiono for the 2022 prize, remarks that the pleasure of reading DisPlace is that the collection consists of “wonderful poetry from a poet who is already internationally important.” This is true of Otiono whose poetic vision in DisPlace comprises the social, as in “Rising Song” and “After the Nooze,” the confessional, exemplified in “The Images Take Wing” and “Through Scorpion-Stings of Suffering,” the elegiac, contained in “Who Can Blow the Smoke Away?” and “In Memoriam: Sole Sister,” and the performative, dramatized in “Midnight Voices” and “This Earth is Ours.”All of this testifies that DisPlace is a notable literary achievement and Otiono a remarkable voice worthy of attention.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions