House of African Feminisms is a website launched by the Goethe Institute and coordinated by Chilufya Nchito. It offers writings, podcasts, and videos centered on African women’s lives. When I first came across the name of the project a year ago, I was struck by the idea of feminism having a house. It conjured for me Virginia Woolf’s “room of one’s own,” that powerful metaphor for the importance of women making, claiming, and taking space. But it also left me with a distinct feeling.

Even though a house is not always a home and vice versa, something about a space for African feminism gave me the warm fuzzies. I imagined a place of fellowship and fun, a utopian world free of judgment, where everyone is welcome, where every voice is heard and every life matters. I imagined a chaotic space because feminists are never afraid to lean into their messiness. Those things that make us different from each other make us alive and human and politically interesting. I also thought of all the many uses of a house – for gathering people, but also for gathering things like books and artifacts, which brings me to the question of the library. A feminist library is a space for collecting media of all forms on the lives of women from all ages. I imagine an African feminist library as a rich collection of books and media that spans disciplines, histories, and geographies. What follows is me wondering what books I’d include in the library if asked to do so, and around what ideas I’d build the selection.

I would begin with the women I call the Ancestors. These are our forerunners, those who went before us to make space for the riches we have today. Buchi Emecheta’s Second Class Citizen, Flora Nwapa’s Efuru, Nawal El Saadawi’s Woman at Point Zero, and Miram Tlali’s Muriel at Metropolitan tell stories of women who challenged the refusal of the world to see their lives as valid. Like the characters in these books, the authors fought for recognition. Ama Ata Aidoo has written about the erasure of African women from the literary canon, how their work wasn’t reviewed, included in anthologies, or paid much attention by scholars. The books in this part of the shelf are special to me because they show the bravery of women who wrote in spite of erasure, silencing, and exclusion. For these women, writing was so much more than an expressive art. It was both a means to survival and a weapon. Emecheta has said that writing kept her sane, but it also helped her channel her rage at a world that wrote her off for the sheer fact of her being a woman. Women like her broke and made the ground on which we stand.

With the Ancestors situated at one bookend, I jump across the intervening decades to our day. The set of books I reach for are by writers I think of as Feminist Guides. These writers offer advice on how to navigate the dangers of patriarchy in everyday spaces. Their writing is a painstaking detailing of the daily and intimate lives of women or what Emecheta calls “little happenings.” Even though their body of work implies a deep knowledge of larger cultural forces such as laws, policies, ideology, history, and so on, it also captures the myriad ways in which these forces manifest in the lived experiences of African women. As the curators of the House of African Feminisms website writes: “feminism is not only a conscious intellectual and activist movement, but a daily lived experience for women.” The writers I have in mind explore and locate oppression and resistance within personal spaces. In Warsan Shire’s poetry collection Teaching My Mother to Give Birth and her new collection Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head, Adichie’s Dear Ijeawele, Titilope Sonuga and Wana Udobang’s albums, Swim and Transcendence, respectively, feminism is how you fight the patriarchy lurking in the household, lying with you in bed, eating at your table. These texts incorporate diverse forms such as recipes, letters, lamentations, incantations, prayers, formulas, secrets, aphorisms, anecdotes, and so on. The writing is clear, concise, and emotionally truthful. It is about providing guides, toolkits, and lessons. No abstractions, no jargons, no posturing. For these writers, the patriarchy is in the micro-moments of everyday life. Feminism is the way you lean into the bonds you share with other women in order to live through a break up, survive puberty, or deal with daddy issues. It is the stream of knowledge flowing through intimate routes of friendships and sisterhood as opposed to towering canons and academic traditions.

Next to the Guides, I place the works of the Sensuous Feminists. Sensuous does not mean sensual. It has more to do with the body and the empire of senses that rules over it than with sexual experience. Writers such as Nnedi Okorafor and Akwaeke Emezi are gifted at making us think about the body, how its fleshiness can both be a space of creativity and limitation. Okorafor’s memoir Broken Places and Outer Spaces is the story of a spinal fusion surgery complication that left her paralyzed from waist down. The memoir documents the difficult journey to recovery and the experience of artistic awakening that occurs along the way. Drawing from a rich genealogy of feminist figures, including Frida Kahlo who also had spinal cord injuries, Okorafor shows how women with broken lives or bodies find a point of gathering and creative empowerment. The book depicts the lived experience of the body as a fleshy, textured, vulnerable entity always seeking to break the human, patriarchal, and imaginative limits imposed on it. Emezi is another author whose work invites a radical rethinking of the body. Drawing on Igbo cosmology, they have built a rich body of work blurring the lines separating the human and the divine, man and woman, and all the other binaries that anchor mainstream thinking on the body. Both in their debut novel Freshwater and their memoir Dear Senthuran, they explore experience as a non-human, as a spirit navigating a human world, and what it means to be a god inhabiting flesh.

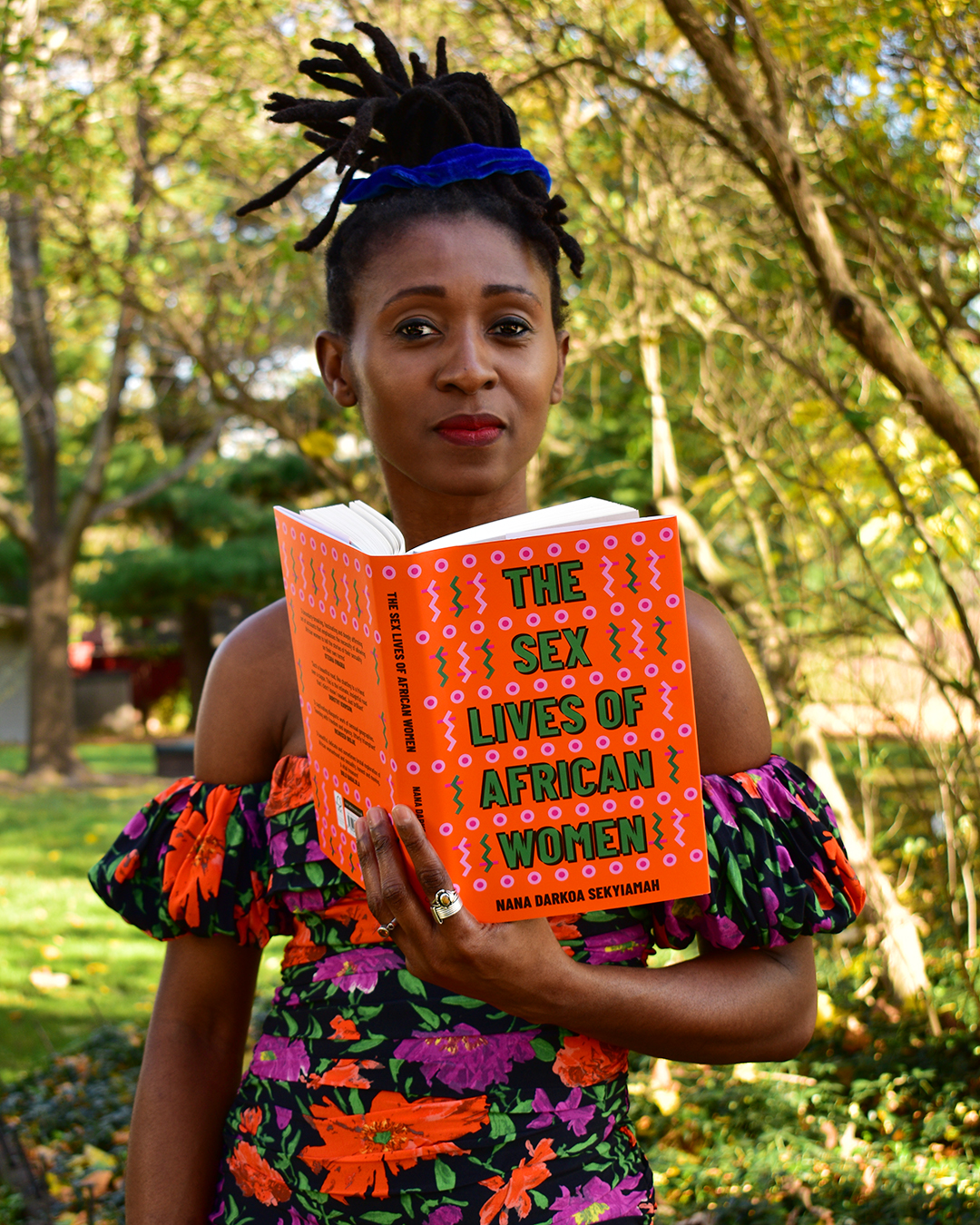

The word “sensuous” was coined by the English poet John Milton to differentiate an experience of the body that doesn’t have the sexual connotations of the word “sensual.” But, as the Oxford English Dictionary points out, it has been virtually impossible to keep both words separate. Sensuous continues to be used widely in the context of sexual pleasure, which is why I count Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah among the Sensuous Feminists. In Sex Lives of African Women, she exhibits the diversity of African women’s sexual experiences. She emphasizes the need to share these experiences in order to “build our collective consciousness around the politics of pleasure.” Secrecy around sexual pleasure is a guise under which various forms of harm is permitted against women. Capturing the textured forms of African women’s sexuality means opening up a space for diverse experiences. Sekyiamah interviewed women from 31 countries. We hear from a woman exploring polyamory in Senegal, one seeking queer communities in Egypt, trans women, sex workers, women dealing with sexual abuse, and so on. Sylvia Tamale’s African Sexualities and Leila Slimani’s Sex and Lies are also on this shelf, as is the ground-breaking collection Exhale: Queer African Erotica Fiction. The multiplicity of ideas about sex explored in these book stuns the reader into abandoning any reductive notions about what sort of experiences fall within the sphere of sexual pleasure in African women’s lives. Sensuous Feminists are students of the body as a space of desire, knowledge, power, and imagination.

Next to the Sensuous Feminists are the Romantics. These are writers using the romance genre to undo the limitations of gender roles and expectations. Romance fiction has not always had pride of place in African literature, in part, because it was perceived as damaging fantasy that obscured the realities of a patriarchal world. But, as Bolu Babalola remarks in a recent piece, “there is nothing hopeless about being a romantic.” Love stories open a space for critiquing patriarchal ideals as much as they uplift women in their search for love beyond domination. Every single book in Cassava Republic’s Ankara Imprint lines the shelf next to Babalola’s Love in Color, an updated retelling of classic tales about love as does her new novel Honey and Spice. All of Jane Igharo’s books, Dudu Busani-Dube’s bestselling Hlomu: The Wife, Lizzie Blackburn’s Yinka Where is Your Huzband, Emezi’s You Made a Fool of Death With Your Beauty, and Adrienne Yabouza’s Co-wives and Co-widows are on the shelf as well. Novels that show the complications of romance in a patriarchal world are also on the shelf: Damilare Kuku’s Nearly All Men in Lagos are Mad, Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay With Me, Noor Naga’s If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English, Ama Ata Aidoo’s Changes: A Love Story, and Piece Adzo Medie’s His Only Wife. This portion of the book shelf is a celebration of love that makes us powerful, instead of small and dispensable. As bell hooks writes, “there can be no love where there is domination.”

The Feminist Militants are the warriors we need now more than ever. They live to destroy patriarchy. Their anger and deep understanding of patriarchy’s systemic operation are their weapons. “I wrote this book with enough rage to fuel a rocket” is how Mona Eltahawy opens her book Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls. The main thesis of her book is that patriarchy undermines the humanity of the feminine, queer, non-white persons by subjecting them to violence. If women are being assaulted, their bodies policed, their voices silenced, we can’t just sit around waiting for “patriarchy to self-correct,” we have to do something. What we do, though, has to be commensurate to the deadly force of patriarchy. Building this force requires bringing up girls differently. Patriarchy thrives on churning out what she calls “good girls,” girls who are trained to obey protocols of oppression. For Eltahawy, feminism is bringing up girls to reject patriarchal ideals of respectability. She calls this revolutionary gesture the act of committing any of seven sins: Anger, Attention, Profanity, Ambition, Power, Violence, and Lust. Each sin marks a space where girls and women exist free of patriarchal control. Engaging in sinful behaviors means breaking down the patriarchal systems of value for what counts as good, beautiful, respectful, innocent, humble, self-effacing, and so on. A world in which women are breaking every patriarchal rule imaginable is freeing in the ways it fosters diverse range of possibilities for lived experience.

One of these possibilities opens up into feminist imaginations of the future, so the next book I pick up is something by a Feminist Futurist. A new trend in African fiction is the rise of science fiction and fantasy. The trend is epitomized in Nnedi Okorafor concept of Africanfuturism, a term she coined to describe fictional world-building that draws from African culture, myth, history, and iconographies. Her novels feature female characters who wield enormous power to build worlds by going beyond spatial and bodily limits. Okorafor is one of the most visible in a growing community of writers placing women at the center of efforts to reimagine the future, but there are others such as Lesley Arimah, Mohale Mashigo, Lauren Beukes, Tlotlo Tsamaase, Namina Forna, Tomi Adeyemo, Jordan Ifueko, Reni K. Amayo, and many more. They are opening space for utopian imagination built on women’s lives. Their gripping stories and lavishly built fictional worlds invite us into female-centered futures.

Next to the Futurists are the Historians. The African past is a highly contested domain of knowledge. For decades, African writers, from Lesotho’s Thomas Mofolo to Chinua Achebe made their name challenging misrepresentations of the African past. Sadly, these correctives to colonial history have incorrectly represented women. In Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, for example, women are shadowy figures existing to provide definition to the actions of male characters. Fortunately, the last decade has seen an explosion in historical fiction by African women. Maaza Mengiste’s The Shadow King on the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, Petina Gappah’s story about Livingstone’s corpse told from the perspective of his female cook, Novuyo Tshuma’s novel on Zimbabwe’s Gukurahundi genocide, Jennifer Makumbi’s Kintu, a modern re-write of an old Buganda tale, Ayesha Haruna Attah’s YA novels on the slave trade in Ghana, Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Tree, Wayetu Moore’s She Would Be King, Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing are just a few. The women in these novels are deeply aware of their world and the forces shaping them. They are not figureheads. They are not archetypes. They are not clueless companions of powerful men. The women in these novels are full of life, flaws, agency, and ideas. We get to see history through their eyes.

The Archaeologists are somewhat related to the historians but not quite. They work on history as one among many forms of knowledge, but their key focus is the process of knowledge-making. Minna Salami’s Sensuous Knowledge: A Black Feminist Approach for Everyone, Panashe Chigumadzi’s These Bones Shall Rise Again, Hello, Buh-bye, Koko, Come In by Koleka Putuma, and Sisonke Msimang’s The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela are good places to see the necessary work being done in this space. The Archaeologists probe the grounding assumptions of our cultures, institutions, and beliefs and tell us where gaps exist. Salami’s book critiques patriarchal ways of knowing by harnessing African knowledge systems. In her collection of poems centered on the life of South African pop singer Brenda Fassie, Putuma examines the intersecting systems of erasure–refusal to cite and exposure of violence—used to exploit black women’s creative and intellectual labor. But she also demonstrates how to counteract this erasure by building genealogies that center their humanity. Msimang’s biography of Winnie Mandela is a study on how to write about women when they have either been so demonized or placed on a pedestal that what passes off as their histories are actually rumors, gossip, and falsehoods. Pumla Gqola’s Rape: A South African Nightmare exposes the underlying assumptions about the political value of women’s bodies that has been used to justify sexual violence against black South African women. The Archaeologists go deep into history to examine the tools we use in building feminist knowledge systems.

Speaking of digging deep to discover new ways of knowing, I complete my shelving with writers who examine the very ground on which feminism stands: the idea of woman. These writers are interrogating the assumptions underlying ideas about gender difference. What is a woman? Who is excluded in definitions based on gender binaries? The criticism leveled at Adichie for her “transwomen are transwomen” statement and the intense debate it sparked opened a space in African feminist writing to examine the ideology of gender. African feminists have critiqued gender roles for nearly a century, exposing them as problematic, but these recent debates show that gender as a framework can also be problematic in the ways that it is used to center heteronormative beliefs about sexuality. It used to be that same-sex love was represented as other in the same way non-binary experiences, more broadly, were banished to the peripheries of the hetero-patriarchal household, which defined much of African fiction. The last decade has seen African feminists invent the language needed to account for the queer, non-binary, trans experiences that have always been a part of African life but that have been erased and silenced. Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Tree, Frieda Ekotto’s Don’t Whisper Too Much, Akwaeke Emezi’s body of work, Unoma Azuah’s Embracing My Shadows, and Trifona Obono’s La Bastarda have all broken various grounds in establishing queer experiences as one of the centers on which African literature revolves.

African feminism is a worldview centered on the realities African women face in a world built on gender prejudice. The archive documenting the struggles and triumphs of these women is infinite. It spans the past and extends into the future. This excise in drawing attention to a handful of give readers entering the limitless archive of African women’s writings possible starting points.

Uju-Nwa Okoye April 04, 2024 22:17

Inspiring, I hope you never stop leaving footprints