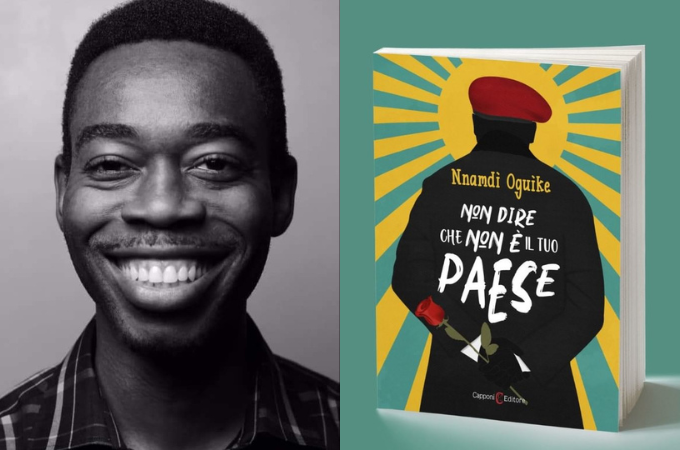

In this interview, the editor and writer, Darlington Chibueze Anuonye, engages the writer Nnamdi Oguike in a conversation about his short story collection Do Not Say It’s Not Your Country and his forthcoming novel Toy Shop.

Nnamdi Oguike is a Nigerian writer. He was selected as The Missing Slate’s Author of the Month for March 2016. His story, “Easter in Jungle City,” won the first runner-up prize in the Africa Book Club Short Story Competition in April 2015, while “I’m Wearing a Wine-Red Smoking Jacket, How About You?” was on the finalist of the 2018 edition of the competition. More of his writing can be found in The Dalhousie Review, African Writer, Brittle Paper, The Threepenny Review, and elsewhere.

***

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Hi, Nnamdi. Congratulations on the publication of the Italian translation of your book, Do Not Say It’s Not Your Country. It is usually difficult for a collection of short stories to successfully break into the global market and the hearts of thousands of readers. But DNSINYC achieved this with incredible ease. In the first few months of publication, it sold more than a thousand copies, was a celebrated presence at the Ake Book Festival in October 2019 and the book-in-focus for Ngiga Book Festival in December of same year. How does it feel to hear your characters speak Italian?

Nnamdi Oguike

Thank you, Darlington. I feel elated. I am pleasantly surprised by how well Do Not Say It’s Not Your Country has done so far, and the reviews it has received have been encouraging. When I finished the first draft of the book and pitched it to a publisher in the UK, the editor asked for the full manuscript, and after a long wait, she told me short stories are a hard sell in the UK, and asked me to rework the collection into a novel. But I believed in the stories. Then Griots Lounge Publishing saw the stories and believed in them. So now you can understand my surprise at how readers across the world have responded to the book. I couldn’t believe it when Italian poet and translator Elisa Audino reached out to say she loved the book and would like to translate it into Italian. The book will be released in Italy by Capponi Editore in October 2022.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

It must have been a wonderful experience working with the translator.

Nnamdi Oguike

Yes, I thoroughly enjoyed working with Elisa. It’s a new experience for me. Italians tend to use more words than the English to express the same idea. Elisa says Italians don’t gesticulate as much as the English, and so put in more words where hand gestures would have helped. It’s such a joy to work with her. Our literary correspondence is the stuff of epistolary novels. And I’ve learnt more facts about Italy. And you know, centuries ago, Italian was only a dialect among many others. But then there was Latin, a departing language, and writers soon got tired of writing in a language that wasn’t spoken in real life. Writers like Dante started using languages spoken in real life. Dante wrote in the Tuscan dialect, which would go on to become standard literary Italian. So, I am proud to be publishing in this rich and beautiful language.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Your forthcoming debut novel seems to be an expansion of “Camp in Blikkiesdorp,” the opening story of DNSINYC.

Nnamdi Oguike

You’re right. You know, some readers of “Camp in Blikkiesdorp” told me they wished to know what happened beyond the end of the story. Initially, I didn’t intend to expand the story in any way, but with the passage of time I thought otherwise, and when the Miles Morland Foundation called for submissions I took a chance on a proposal that drew from the richness of “Camp in Blikkiesdorp.” Although the novel shares some characters with “Camp in Blikkiesdorp,” it is a different story, with more settings and preoccupations than “Camp in Blikkiesdorp.”

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

How would you describe the experience of winning the 2019 Morland Scholarship, which provided you with the funding to complete the novel?

Nnamdi Oguike

Winning a writing scholarship was a life-changing experience. I wouldn’t have been able to write my debut novel without the scholarship. As soon I was shortlisted for the Miles Morland Foundation Writing Scholarship, it seemed as if a dam of ideas broke in my head. I started gestating and making notes. But the actual process of writing began after I was awarded the scholarship, I felt unhinged as far as the act of writing was concerned. I didn’t have to worry about food or bills and I wrote every day. I totally relished the feeling of being a full-time writer in 2020. It’s an experience I wish all writers could have, because it is extremely difficult for artists to work when hungry or homeless or consumed by worries of debt. I can only imagine how much literature Nigerian writers can turn out if supported through residencies or writing scholarships. So, for me, during my scholarship year in 2020, it was a happy ritual of sitting at my desk and typing away.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

You worked closely with Giles Foden while writing the novel, how was the experience?

Nnamdi Oguike

It was a huge privilege to have Giles Foden, author of The Last King of Scotland, give feedback on my novel, then titled “Toy Shop.” Foden is the fiction consultant for the Miles Morland Foundation. As soon as I had produced my first draft of the novel, the Foundation forwarded it to Foden, who read it and provided a wonderful feedback. He gave his impressions about the book and suggested how to improve it. I was totally surprised by what he said about the book. He was impressed with the quality of the writing, said it was an excellent novel, praised its character development, its control of feeling, and the way the novel presents the personal and the historical. I was blown away by his comments. And it was a first draft. The novel has passed through many drafts since then. I have also changed the title of the novel, on the advice of my literary agency in New York, The Leshne Agency. But I enjoyed that experience with Foden.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Let me add to Foden’s observation, you write about tragedy with such surprising humour. That’s an incredible skill, a necessary talent in these angry and sad times. Your short story, “Prophet,” illustrates this. In its satiric wit as well as its exploration of the exploitative tendencies of religious institutions in most parts of Africa, “Prophet” reminds me of Wole Soyinka’s The Trials of Brother Jero. How did you come so close to the heart of humour?

Nnamdi Oguike

Most of my family members are humorous people, and so I think humour comes naturally to me. I doubt if I can write any piece that hasn’t got a line or two that lightens the mood. T.S. Eliot said, “Humankind cannot bear very much reality.” That is so true. Our realities are different and sometimes unbearable, but art can make some of these things, whatever they are, bearable. I suspect that if one sets out to write a work that is unchanging in tone or mood or intensity, it will be unreadable. There’s a tendency, when one is writing about traumatic or tragic situations, to be overwhelmed by them, with the unfortunate result that the writing reads like a jeremiad. I think a good writer should strive to achieve some balancing act in their work. I try to balance seriousness with lightness, brightness with darkness, beauty with ugliness, happiness with grief, surplus with deficit, etc. I take a lot of my literary training from music. Great musical compositions play with contrast. Composers understand that without variety in theme and tone and colour, the listener will get bored. It’s the same with writing. So I always aim to achieve variety in my work in order to hold the reader’s attention throughout.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

I imagine that art will be dry without humour.

Nnamdi Oguike

Yes, humour helps a lot.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

In DNSINYC, there are stories set in South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, Libya, etc., each expressing with an almost indigenous knowledge the lives and cultures of these countries and peoples. The collection must have called for much research.

Nnamdi Oguike

Throughout the period of writing the book, I was constantly curious about what was different from my locale. And I say the word “different” with utmost care. There is sometimes a disingenuous emphasis in the world about how different we are. I am aware of the differences. But I’m interested in our shared humanity. And that’s the grand theme of the book. For me, fiction or literature is not really about life in different places; it is what life does in different places. And that life is human life.

In DNSINYC, the differences appear in settings, cultural peculiarities, language differences, and so forth. I was always eager to find out about these peculiarities. How do Malagasy people in Madagascar say hello or yes or no or please? How do people say thank you in Kenya? What does Susan’s Bay in Sierra Leone look like? And so forth. I asked people who know these things better than I do, or people who live in, or have lived in, these places. I collected lots of photographs of those places, read reportage on them, books, etc. I surrounded myself with these findings, sucked as much as I could out of them and allowed them to take shape organically in my mind. And then there was the most difficult part of the job: what should get in and what shouldn’t. A piece of writing, no matter how long or short, isn’t an infinite space. So you can’t afford to chuck in excess detail, or you’ll ruin the work. Then it will read like reportage. I’m constantly reminded that the short story is not a register of facts, but a vehicle of experience. The same can be said of the novel, the poem, or the play. And writing is a lot like culinary art. Too much of any ingredient ruins the cuisine. So I couldn’t afford to use all the materials I gathered for the work.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

I agree with you, “literature is not really about life in different places; it is what life does in different places.” One reading of “A Passage Through Libya” shows just how fully human you are. Not just that, you follow the human life and experience with a humane care and interest. Like Chika Unigwe’s On Black Sisters Street, which documents the complicated experiences of African migrants in Belgium and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, which explores the conditions of Africans in America, “A Passage” devotes so much passion, understanding and tenderness in rendering the lives of its African characters exiled, trafficked, dehumanized, commercialized in Libya. It is a heartbreaking tale, “a human life,” to borrow your words. How deep is that life?

Nnamdi Oguike

For my fiction, I see human life in the light of its complexity. And this consciousness guides me when I’m creating and developing my characters. Human beings are never one thing. Nobody is ever just one thing. Same goes for countries, ethnic groups, and races. At the core of our nature is an interplay between things that are beautiful and things that are not beautiful, between what is good and what is not good. There’s a common phrase that tries to capture this complexity: the good, the bad, the ugly. These are all present in human life. They are present in all persons I know. They are also present in every country or people. We become disingenuous when we describe a person or a group of people as wholly good or wholly evil. I suspect something underhand whenever I read a book in which people are described or painted in one broad brushstroke. There’s a single story problem there. That’s the reason why a lot of the characters I create, such as the ones you find in “A Passage Through Libya,” are complicated characters you may not love entirely. I mean, who loves everything about anybody? So as an artist, I strive to speak to our capacity for delight and wonder, to the sense of mystery surrounding our lives, our sense of pity, beauty, or pain. I’m paraphrasing Joseph Conrad here. But that speaks to the complexities of human life.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

I think this line captures the central message of “A Passage”: “I have never heard language so robustly spoken. We clap for him for his linguistic credentials. But something bad happens to this good and cheerful cosmopolitan and to us before we get to see the one who will take us to the one who will take us to Lampedusa.” Such is the tragic uncertainty of the exile’s life. What inspired this story?

Nnamdi Oguike

A lot of my stories were inspired by real life events, history, journalistic reportage, photographs, video clips, and books. But I have to have an emotional connection with these materials before I believe I can write about them. “Camp in Blikkiesdorp” was inspired by the outrage caused by the construction of tin shacks in Blikkiesdorp for poor people ahead of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. “Breaking News,” set in both Zimbabwe and South Africa, was inspired by the ousting of President Robert Mugabe. “The Message,” which is set in Mali, is my fictional take on the Tuareg separatist rebellion in Mali and other countries where the Tuareg people live. “My Beloved Infidel” draws a lot from the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria. In the case of “A Passage,” I had read about modern slavery in Libya in the aftermath of Muammar Gaddafi’s fall. I was outraged by it. When I learnt about slave markets in Libya where black Africans were bought and sold as chattel, I decided to explore the experiences of the victims through fiction. Most of the victims of slavery in Libya, I realized, were people who dreamed of a better life for themselves and their families. They wanted to migrate to Europe in search of better lives. They sold property or borrowed money from friends and relations. And they got agents who connected them with people who could put them on migrant boats across the Mediterranean Sea or lead them across the Libyan desert towards Italy. As we know, lots of these migrants either perished at sea or in the blistering desert. But there were some who didn’t make it to the Mediterranean or the desert. They ended up in slave markets. They were seized like sheep or cattle, bought or sold, and sent to work in farms, construction sites, or factories without pay. They were poorly fed, became too thin, got sick, or died. This was the fate of many black migrants in Libya, and one cannot approach this reality without a brave heart. I set out to write a story about this reality but not as a journalist or reporter would do, reeling off tales of woe and misery, and tying up the reportage with statistics. I wanted to tell a story about this modern form of slavery through the eyes of a Senegalese man named Diallo. I wanted to explore his hopes and dreams, his predicament and suffering, and his failure to actualize his dreams. But the story isn’t just about the Senagalese; it is also about people of other nationalities. In the slave market, we meet victims from Nigeria, Gambia, South Africa, Ivory Coast, Togo, Zimbabwe, Liberia. So, in a way, the story presents a slice of reality in African countries. It is a story about the misery of fellow human beings and about man’s cruelty to man, which can be seen in any other part of the world, perhaps in modified forms. But I was challenged by how best to tell the story without being sensational; I remember cringing while writing some portions of it. But I think humour makes it easier to read. The language helps, too. I kept it simple; not preachy. And we can see that even though human beings can be treacherous and cruel, they can also do a lot of good.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

“The language helps too.” These words remind me of Toni Morrison’s articulation of the power of language: “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.” What is your relationship with language?

Nnamdi Oguike

My relationship with language is the same relationship that a painter has with oil or acrylic, or that a sculptor has with marble or clay. Language is a vehicle to convey phenomena or human experience or condition. A writer’s style is a demonstration of their character, in the same way that a painter’s brushstrokes can tell the artistic temperament of the painter. Or the way a musician strums their guitar or strikes their piano keys. Or the same way an operatic singer approaches an aria. No two artists are the same. And in writing, description is also very political. Every adjective reveals an opinion of the writer about things; every adverb does the same thing; every verb; every noun. So words are never as innocent or innocuous as they seem. They are actually as powerful as when people go out on the streets to say, “Down with the Prime Minister!” or “Down with the President!” or “No to Racism!” or “Save the Planet!” Words are powerful. That’s why we do language. And that’s why the Christian idea that God created the world with words fascinates me. That is how important I think language is. I try in my writing to be simple and profound at the same time. I try to be light and serious simultaneously. I love drama. But I love clarity. Writing in a clear language doesn’t mean you can’t write in a rich language. I think a lot of writers who don’t achieve clarity have a lot to say but do not know how to say them. I do not believe one should be applauded for being vague or confusing. But profundity, whenever it shows up, deserves accolades. I also take very seriously the freshness of language. Language that stands out like fresh groceries. Who would like to eat withered, trampled, sun-dried groceries? That’s how I see clichés. I find clichés almost unforgivable. A literary writer must keep searching for fresh ways to render thought.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

There is also empathy in your writing. I first experienced this when I read your short story, “A Nice Job in Antananarivo.” I felt the suffering of the young orphaned brothers. I did not just feel. I saw myself at some point partaking in their grief. I was nearly one with them. So profound and visceral was my involvement in their lives that I wished I could lessen their suffering. Imagine my joy when finally the new job turned out to be a source of joy to them. It’s redeeming. I like that the story returned me to the playground of my childhood where innocence is mined and joy is released. How you did feel writing “A Nice Job in Antananarivo”?

Nnamdi Oguike

I wrote “A Nice Job in Antananarivo” in an air of childhood bliss. That’s how I can best describe the feeling. It was one of the stories I thoroughly enjoyed writing. I am happy that you connected with the story that deeply. I am somewhat surprised when reviewers of my book talk about their “Big Five” stories of the book, and I don’t see the Antananarivo story. The most popular ones have been “In Our Father’s House,” “My Beloved Infidel,” “Kumba’s Sister” and “Camp in Blikkiesdorp.” But writers cherish their stories differently. So “A Nice Job” is a personal favourite. It evoked my best childhood years, the beauty and wonder of my innocent years. But, as with most of my stories in the collection, I was fascinated by the geographical and cultural appeal of Madagascar. I mean: look at the elegant island country in the midst of the Indian Ocean. Who wouldn’t be fascinated by it? And then a panoply of the longest and most beautiful names I have ever known. I had, for a long time, been enchanted by Malagasy names. There’s a sweet cadence to their names. There is also a flavour of French names, but the traditional Malagasy names are more delightful. Very alliterative. Many of them sound like a performance on a percussion instrument. Some others are mellifluous. Collecting Malagasy names was a favourite pastime of mine. I believe I chose some of the finest for my stories. Rakotomanana. Ranomenjanahary. Veloraza. Rasoa. Rahelisoa. Fanampesoa. Fandiferana. And the father of the Malagasy people had one of the longest names in the world: Andrianatompokoindrindra. It is a towering, magisterial name.

Equally delightful are the names of places: Antananarivo. Vontovorona. Ankasina. Madagascar never disappoints with names.

You referred to the grief in the book. Life, even that of a child, is often flavoured with the bitter taste of loss. But again I was fascinated by some aspects of Malagasy culture. The kind of houses people live in, among the old people and the younger generations. And the funeral ceremonies. There’s an old practice among the Malagasy known as Famadihana, in which dead bodies are exhumed after seven years and re-buried in a different place so that the dead can continue their journey into the next world. That was intriguing, for me. But a general sense of childhood delight and fun that pervades the story, a lot of which is deliciously served by the little, feisty, and importunate Lala. I, too, was helplessly rooting for Rasoa to succeed.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

You were “rooting for Rasoa”? This warms my heart. What happens when the writer connects so viscerally and empathizes so deeply with their character?

Nnamdi Oguike

It is a beautiful thing to connect deeply with my characters. They, after all, originate from me. They are my creation. They are like my children. And so I give my characters sufficient attention and care, feeding them time, depth and heft. That’s how we bring about character development. When we care deeply about them, they’ll come across as natural and believable characters. They’ll be complex, just as every human being is complex. They’ll also not come across as characters demonized by the writer. Even flawed characters won’t come across as zombies. The reader will understand why they do the things they do.

My characters are never exactly like me, even those that I connect very deeply with, like Rasoa or Sindisiwe. So I make sure not to impose my idiosyncrasies on them. At the same time, I do not give them the latitude to do as they please. At the end of the day, it’s my book, not theirs. It’s their story, but it’s my book. It’s like a family, and no parent can afford to give their little children unlimited freedom. They must recognize the freedoms of others in that family. I don’t have the same degree of affection for all my characters, but I can’t afford to have a character stifle the rest of my characters, or edge them out of the book, except if that is my wish.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Thank you for giving a voice to things that would have remained unspoken and to characters that would be remained silent. I look forward to reading your novel.

Nnamdi Oguike

Thank you so much, Darlington. All the best.

Reginald Oguike October 23, 2022 13:25

Very impressive work. I congratulate Mr. Nnamdi Oguike for such a wonderful story that's already making waves.