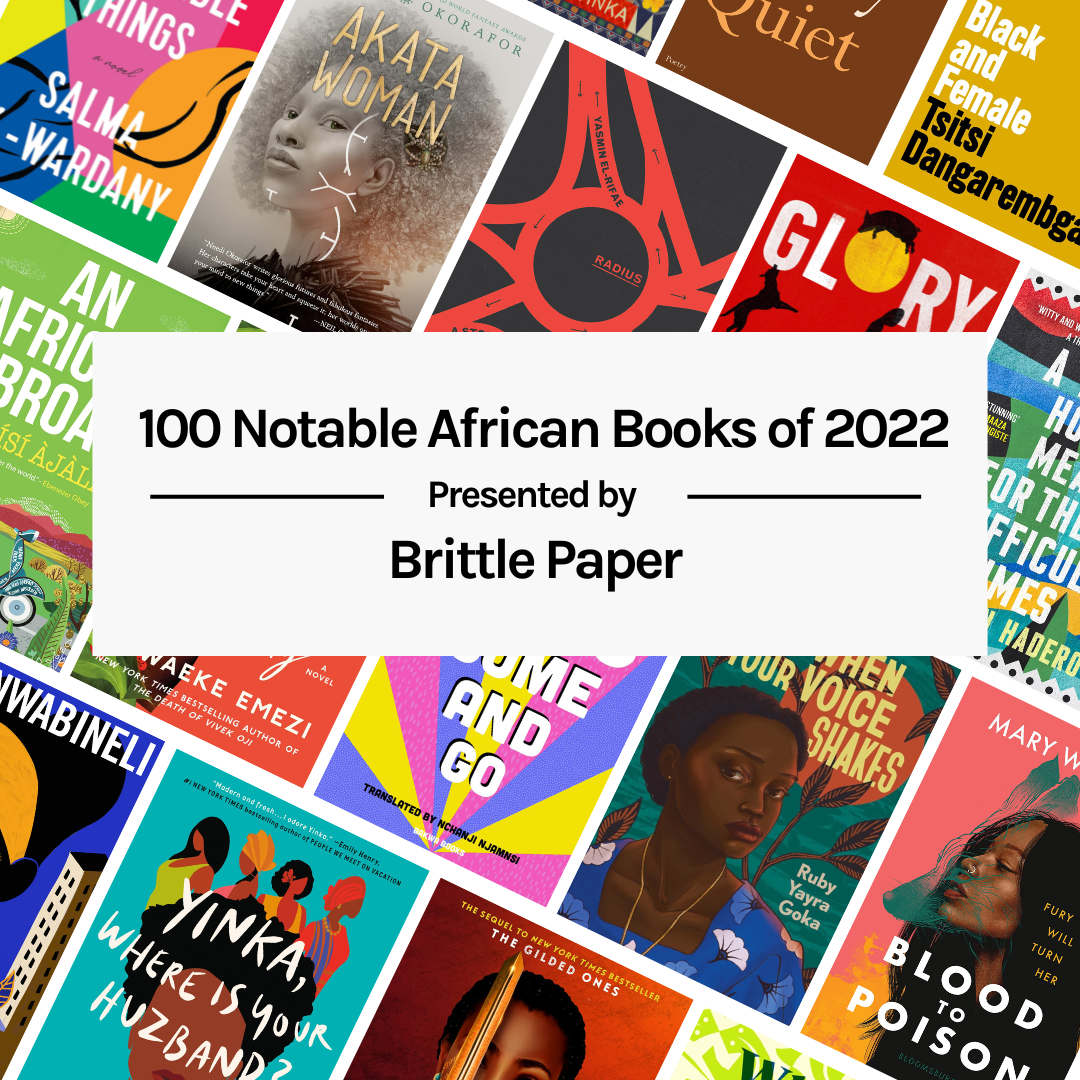

African writers are producing excellent writing, and publishers, both on the continent and the diaspora, are making space for their work. This year, we expanded our Notable African Books of the Year list from 50 to 100 because of the large volume of good books published. [See here if you missed it.] The expansion of our list is part of a larger story about the culture—how it is growing but also facing new challenges. One advantage of curating this kind of list is that you get a broad sense of which direction things are going. Here are a few trends we observed from drawing up our notable African books of 2022 list.

1.Debut Authors: The number of debut authors being published are on the rise. This year, debut authors account for 1/3 of the 100 books on our notable African books of 2022 list. This is sign of a growing market. It tells us that African literary culture is expanding by adding new voices and not solely by publishing established authors.

2.Visibility of Women: We also saw more women representing the culture. Usually, we begin the selection process with a large pool of books. This year over half were by women. The last few years have seen African women becoming more visible in the global literary space. This trend is not slowing down and is significant for a literary culture that has been historically male dominated.

3. Diversity of Genres: What we saw from curating our list is a diversity of writing. There appears to be a sense of freedom among writers to explore writing styles and forms. Speculative fiction is still on the rise and not looking like it will be slowing down any time soon. It used to be that African writing was mostly highbrow literary fiction. This year, romance, crime, sci-fi, fantasy, comic books, and YA took a healthy chunk of the literary real estate.

4. Boundary Pushers: We want to raise our glasses to the many African writers who are challenging literary norms. For example, Chinelo Okparanta and NoViolet Bulawayo’s novels published this year, Harry Sylvester Bird and Glory, respectively, are unapologetically experimental. It is always a risk when authors push boundaries in unusual ways, so kudos to them. Authors such as Akwaeke Emezi, who are pan-generic, are also challenging conventions on what is expected of a writer. This year, they published three books, in three different genres. Wow!

5. Adventurous Readers: We also have to give kudos to readers. Implied in the idea of a risk-taking author and an expanding literary space is a reader who is willing to try new things and stretch their palate. Readers of African literature seem more open to an expanding sense of what African writing is.

6. Screen Adaptations: This has been the year of movie and TV options: Masande Ntshanga’s Triangulum, Helon Habila’s Waiting for an Angel, Ayesha Harruna Attah’s Zainab Takes New York,Tola Okwogu’s Nneka and the Academy of the Sun, JJ Bola’s The Selfless Art of Breathing, and others. This flirting between African literature and the film industry is welcome development. It means more capital flowing into the culture, as well as more zones of creative expression.

7. Western Publishers: Not all the trends are positive. For example, the bulk of African literature making their rounds globally are still those published by presses in the west. Their writers are also more likely to win awards and snap up translation rights and film options. This means that the bulk of the money generated around African books is locked in western publishing markets. That needs to change.

8. Fiction is still King: Poetry, children’s books, and autobiographical writing made a good enough showing, but the books published this year shows that fiction is still the king of all genres, in the African literary world. Strategic institutional investments by the African Poetry Book Fund in African poetry is paying off. We are seeing a rise in poetry publication and an increase in visibility as these books win awards. But fiction remains the favored genre.

9. Translations: We need more translations in English. Kudos to Iskanchi, Bakwa, Cassava, and others who published translated works this year. But we need more. Translations open the English-reading space to literature from countries that would otherwise be excluded from the culture. The reason we can read works such as Why Do You Dance When You Walk by Djiboutian author Abdourahman Waberi, Days Come and Go by Cameroonian author Hemley Boum, The Night Will Have It’s Say, by Libyan author Ibrahim Al-Koni and So Distant From My Life by Burkinabé author Monique Ilboudo is because of translation.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions