I

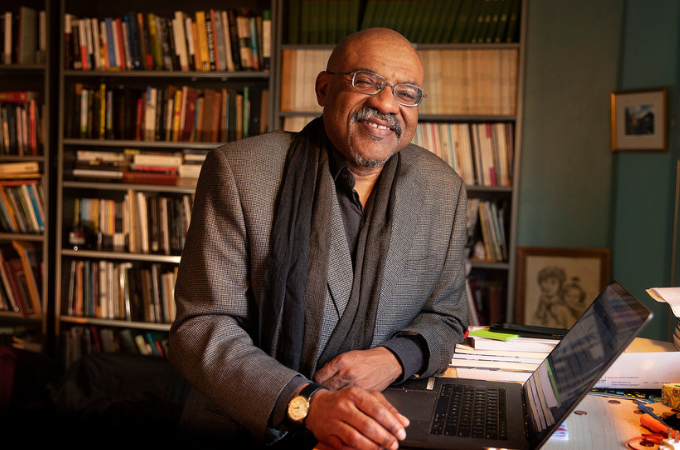

Brittle Paper’s Literary Person of the Year award, now in its 8th year, recognizes an individual who has done outstanding work in advancing African literary culture and industry in the given year. The 2022 honor goes to Prof. Kwame Dawes for his work on building institutional and industry support for African poetry.

In 2012, the year Kwame Dawes established the African Poetry Book Fund in conjunction with the University of Nebraska, where he is currently a George W. Holmes Professor of English and Glenna Luschei Editor of Prairie Schooner, he had a clear idea of what he wanted to achieve with the initiative. He started small, with the poet Chris Abani and a supportive cast of dedicated people. In the years since, the project has exceeded his expectations. It has become the anchor for contemporary African poetry. In my recent interview with him, Dawes spoke of how “the enterprise has been a blessing” for all involved and how “the last few years has been a high point” in his life.

The African Poetry Book Fund (APBF) project includes the New-Generation African Poets Chapbook Box-set series, of which Dawes is the series editor; the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poetry, awarded to an unpublished debut poetry manuscript by an African poet and financed by Laura Sillerman and Robert F.X. Sillerman. Other initiatives include a research project on the distribution of poetry books in Africa and the African Poetry Translation Series, established to support African and Caribbean poetry, already starved of visibility in a publishing world where poetry is not prioritized. The institutions that Dawes helped establish have become an integral part of the trajectory of contemporary African poetry. APBF’s stated aim is to promote “the poetic arts through its book series, contests, workshops, and seminars and through its collaborations with publishers, festivals, booking agents, colleges, universities, conferences and all other entities that share an interest in the poetic arts of Africa.”

How has APBF impacted African poetry? To understand this, one has to go back to the early beginnings of African poetry. Beginning in the1950s, when the modern generation of African poets came of age at the University College Ibadan and Makarere University—Wole Soyinka, Christopher Okigbo, JP Clark, Chinua Achebe, and Okot p’Bitek—modern African poetry grew to some significance in African literature. But, the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s saw a gradual decline, not only in the visibility of African poetry but also in poetry’s overall standing in the global literary market. What little poetry that came out during this period was published by already established voices; there was no clear pathway for the development of younger voices. Matters were not helped by the seeming prioritization of fiction, which was seen as more viable and accessible. This explains why many African novelists were winning international literary prizes at a time when not much new poets were coming out of the same milieu. This austerity of interest and the absence of institutional support for African poetry inspired the establishment of major initiatives such as the Brunel International African Poetry Prize in 2013 by Bernardine Evaristo and the African Poetry Book Fund.

Dawes’ attempt to resuscitate contemporary African poetry and raise a whole new generation of African poets to continue an age-old tradition and legacy at a time when there was no source of inspiration or prizes shows how much of a trailblazer he was, in the company of the likes of Evaristo and what she achieved with the Brunel Poetry Prize, now known as Evaristo African Poetry Prize. In establishing the prize, Evaristo expresses her belief “that poetry from the continent could also do with a prize to draw attention to it and to encourage a new generation of poets who might one day become an international presence.” True to Evaristo’s dream, past winners of the prize, like Warsan Shire in 2013, Safia Elhillo in 2015, and Romeo Oriogun in 2017 are now global literary stars. By their exceptional literary commitment, Dawes, Evaristo and visionary group of colleagues have succeeded in keeping African poetry in the global literary scene.

II

Kwame Dawes’ unique personal biography might have played a role in his visionary sensibility as a poet, a scholar, and culture influencer. Coming from an artistic background, he was born in 1962 at a time when his father, the Nigerian-Jamaican novelist and poet, Neville Dawes, was teaching at the University of Ghana. With parental roots in Nigeria, Ghana, and Jamaica, and having been educated across these geographies, including years of postgraduate studies in New Brunswick, Canada, and subsequently working and residing in the United States since 1992, Dawes could be said to represent the modern hyphenated identity. His links across the African and Caribbean world is deeply felt. He acknowledges the unique disparity that exists in opportunities for writers in these places compared to America. “Poets,” Dawes says, “have always understood themselves to be part of an ancient tradition that dates back to antiquity. Unfortunately, racism and other forms of power dynamics have limited our understanding of the threads of this tradition in parts of the world that were exploited. The fact is that rich and sophisticated poetic practices and traditions have always existed in African societies and continue to thrive in Africa.”

In the struggle for literary relevance, African poets took on a style that became essentially more democratic, and no longer the inaccessible obscurities of older poetry. Remarking on the stylistic transformation in contemporary poetry, Dawes in a video interview with Furious Flower, acknowledges the presence of what he calls “the body,” “the silences” and “the noises” in contemporary African poetry. His interest, he says, is in poets that destabilize the old to invent and reinvent the new, poets who go further in their exploration of the limits of language. On this level, he adds, is where some of Africa’s best young contemporary poets operate; the likes of Shire, Ladan Osman, and Oriogun. Dawes reiterates his commitment to these poets, and others like them, to get to the absolute limits of their creativity.

Saddiq Dzukogi, a brilliant young poet, whom the APBF initiative has helped, describes Dawes’ influence glowingly. “Before I met Kwame Dawes,” he says, “I never wanted to be like anyone. All what I am now, is because of him really. Watching him, talking to him, listening to him, changes you. He is easily one of the most important people in my life. I think one of the most important parts of Dawes life as a promoter of art, particularly African poetry is that he only wishes to center the writers whom he is in service for, till the land, make the path and encourage them, writers who are perhaps lost on the fringes of attention, to journey through, being fully themselves and the voices of their people. He literally works day and night for the advancement of others, and I believe finds immense joy in offering his time, intellect, and vision, and even his resources to make that a reality.” Dawes has done much work to promote contemporary African poetry from relative obscurity to considerable visibility, with a corps of gifted poets of African descent.

III

The latest project, and perhaps the most massive so far, being run by Dawes and his team, is The African Poetry Digital Portal, which he launched in 2017. The stated aim of the project is to document the work of African poets by providing digital access to its wide-ranging scope of research materials and creative works. In August 2021, the project received a three-year grant of $750,000 from the Mellon Foundation. The project, according to Dawes, will “give poets a chance to engage the tradition as part of their understanding of the poetics of form and practice.”

In Kwame Dawes’ world, obviously, what matters is poetry, the continuation of its legacy into posterity. For African poetry, Dawes sees something beyond the present, even as he has created greatness and visibility for Africa poets of the here and now.

Let me end by citing Tryphena Yeboah’s honest and moving remark on Dawes: “Whatever goodness and excellence are projected in the world about Dawes, they are richer and more delightful in private.”

I congratulate him on emerging the Brittle Paper Literary Person of the Year 2022.

Ijeoma Richards December 23, 2022 07:02

Impressive. Seems well deserved