Nomad, Romeo Oriogun’s second full-length collection of poems, is a creative documentation of memories and movements, an interrogation of history and historiography.

Forced into exile by his country’s laws that criminalize the existence of the queer person, Oriogun’s previous collections were dedicated to the understanding of the lives and plights of queer people in Nigeria, those he referred to as Burnt Men, whose bodies are seen only as faggots waiting to be lighted. In Sacrament of Bodies, Oriogun offered a theological as well as physical redemption of these queer bodies which have become a site for violence and unspeakable terror. Oriogun uses the same confessional style of these earlier collections to excavate the terrors of movements in Nomad.

The poems in Nomad are personal. The collection, a memoir in verses, opens with a poem titled “The Beginning,” chronicling the poet’s migration experiences from Ghana to the United States and beyond.

Before the bus sped towards the border,

I was tender – a lover of my city gathered

into a singular prayer of leaving.

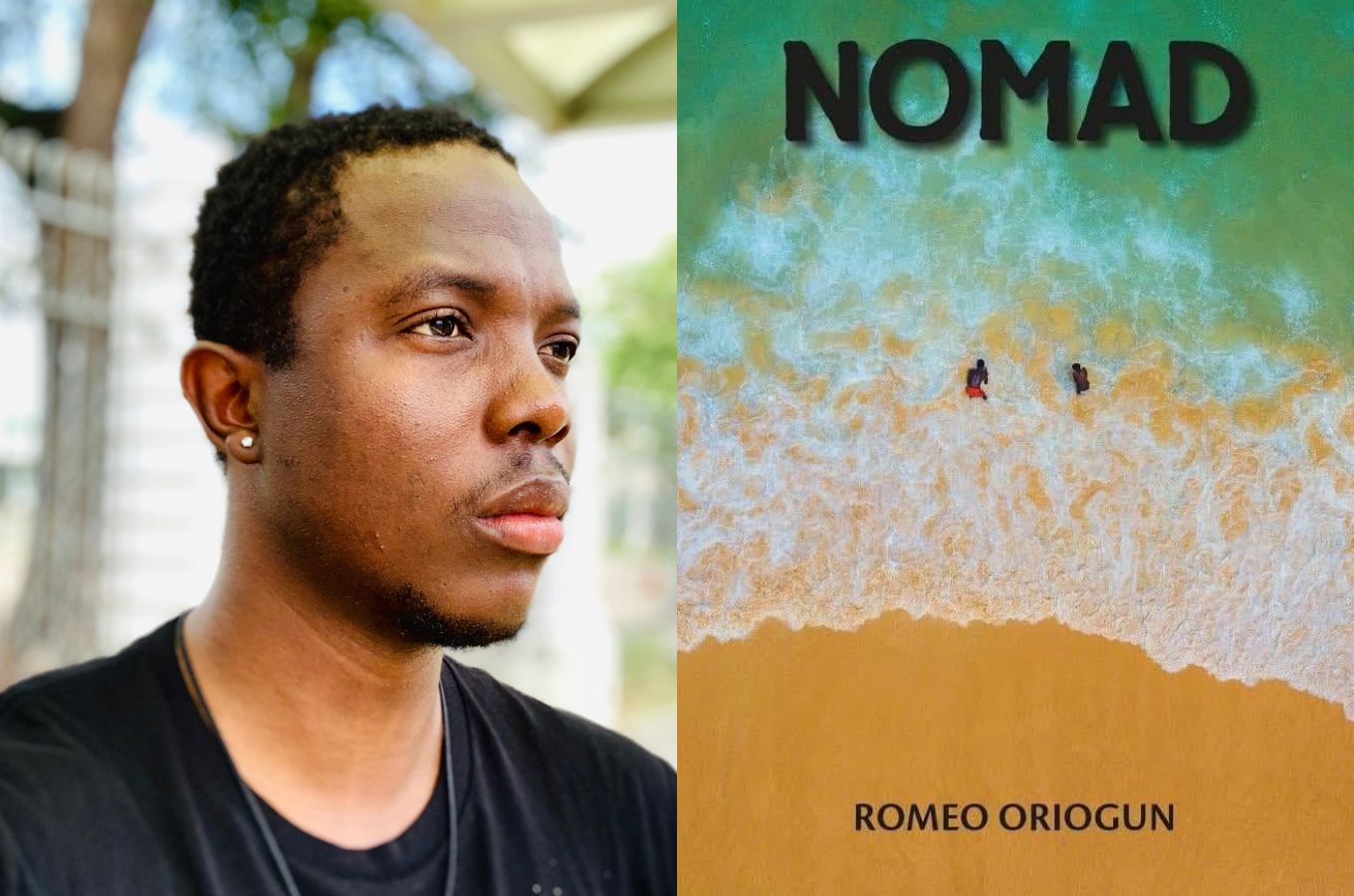

For, to the rejected queer person, who has “committed no offence except to love a man,” to leave is to live, to negotiate a state of being. With this opening poem, the subject of migration whose seed was sown by the collection’s title and cover image – an aerial photograph of two black men shirtless and scooping water at the bank of a river, an indication of freedom and fluidity – takes root and grows into sixty-seven branches of verdant green poems. Oriogun’s migration, he notes, is not a case in isolation; a plumbing through history teaches the origin of this forced migration, of the slaves taken through Ouidah to plantations where they were dehumanized and exploited. The forced movement of these slaves birthed the poet’s forced movement. By making this connection, Oriogun sets a pattern of engaging the world only on his own terms, of interrogating colonial legacies and the posturing of postcolonial rulers.

Just like the theme of migration, water is a motif that runs throughout Nomad. Like movement, which has the ambivalent nature of being both the “history of life” and an embodiment of terror, water is not just an innocent essential in the life of humans. It is also a repository of the “violence of history.” It is through water that the colonizers came into Africa. It is through water that Africans were carted away to slavery. The sea as the entrance portal of the colonizers and the slave traders has made it impossible for the colonized to forgive one another, to heal from the trauma of their existence. The reality, as the poem persona in “Killing the Condemned” notes, is that for the colonized, “forgiveness is ours if only the sea didn’t flood the land / with canons.” Yet, the sea sometimes provides escape routes for queer people whose desires are their country’s greatest fears.

Nomad is Oriogun’s attempt at answering the question, “what will poetry offer me.” It is his revelation of the salvific nature of poetry, of the elevated place of language in human existence. “Only language can begin the restoration of those pushed out of history,” the poet insists. This is the restoration he attempts to make when he speaks of the victims of the Biafran war, of the slave market formerly at Ouidah, of the Asaba massacre, of his deceased mother, of the abandoned town of Kolmanskop in Namibia, and of the recent killing of innocent young Nigerians at the Lekki tollgate. He achieves this restoration by providing excerpts from the speeches of the victims and witnesses of the brutalities he writes about, especially with the inclusion of the speech of Mrs. Ewonemen Ewu of whose name in a quick Google search shows nothing. Like many victims, her story has been confined to the darkness of forgetfulness. By transmitting her words thus, Oriogun shouts her into light. Oriogun’s restoration is akin to Achebe’s, a reminder that ours is not a “one long night of savagery,” subject to men “who declared that we were half-humans, then full humans, then people who could read.”

The full beauty of Nomad is not to be found in its themes. It is not even in the sharpness of the poet’s memory that is “like a blade / that has refused to be dulled into time.” Nomad’s full beauty lies in its use of language, its feast of metaphors. Affording the detachment that comes with time, the poet speaks in a measured, precise, and soft voice filled with such lushness of narration that an inattentive reader may miss the existential angst that runs throughout the collection. Oriogun is a storyteller who has opted for the crispness of the verse.

***

Buy Romeo Oriogun’s Nomad here: Amazon

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions