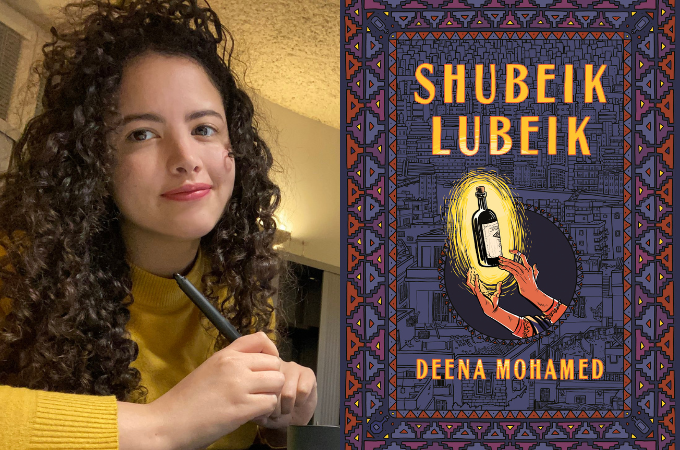

Egyptian writer and illustrator Deena Mohamed recently released her debut graphic novel Shubeik Lubeik on January 10. It is currently Amazon’s #1 New Release for Literary Graphic Novels. Published by Pantheon Books, an imprint of Knopf Doubelday, the book features a fictional Cairo where wishes are for sale.

Originally published in Arabic by Dar el Mahrousa in Egypt, Shubeik Lubeik was awarded Best Graphic Novel and the Grand Prize at the 2017 Cairo Comix Festival. The title of Mohamed’s novel Shubeik Lubeik means “your wish is my command” in Arabic and refers to the central plot device in the book.

From talking donkeys and dragons to cars that can magically avoid traffic, Mohamed’s magical Cairo features all kinds of wishes for sale. However, the production and distribution of these wishes are based on capitalist logic. The more expensive a wish, the more powerful and reliable it is.

A New Yorker article breaks down the hierarchy of wishes in Shubeik Lubeik:

For the most part, first-class wishes, which are known for their “generous interpretation,” strive to understand, and fulfill, their wisher’s true intention. Second-class wishes are of middling strength. When pushed past their limit, their effect is temporary. Third-class wishes are cavalier, treacherous—or perhaps capable of humor. You may ask for money and end up with Monopoly money. You may wish for a car and end up with a model toy car. If you try to outwit the wish by asking for a Mercedes-Benz with “manual four-speed transmission and one-two-four-point-oh-two-one chassis code engine model,” you may end up with a Mercedes-Benz with manual four-speed transmission atop a minaret that insures it can never be reached. Such “bad-faith interpretation” has earned third-class wishes the street name Delesseps—a sneering reference to the late French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps, the developer of the Suez Canal who betrayed Egyptian anti-colonial revolutionaries.

This system of wishes feeds into the class hierarchy within Cairo. The working class may work twice as hard to earn the money to buy first-class wishes, yet the corrupt government tries to confiscate these wishes and reserve them for higher-ups by detaining low-income people and forcing them to sign away their wishes.

Mohamed’s novel uses the metaphor of wishes that can be bought and sold to construct a brilliant satire of the global extraction economy. Mohamed brings to life three main characters who view these wishes very differently:

- Shokry is the owner of a kiosk in Cairo that sells wishes. However, he is wary of using the wishes himself for fear of compromising his Muslim faith.

- Aziza, a low-income widow, comes across the kiosk and manages to buy a first-class wish after saving up. However, a police officer arrests her and accuses her of having stolen the wish she just bought. Caught in a bureaucratic loop, Aziza is helped by the Wishes for All Foundation that fights for equal access to wishes.

- Nour, a wealthy college student majoring in Wishful Thinking and Philosophies, also buys a wish at Shokry’s kiosk. Nour struggles with depression and must decide whether to use their wish to try to “fix” this depression.

Shubeik Lubeik uses wit and humor to describe a world where wishes function as a kind of wealth within the societal hierarchy. Mohamed brilliantly portrays the struggles of characters such as Aziza who have to fight for the right to use as well as enjoy a first-class wish.

Deena Mohamed is an Egyptian designer, illustrator, and writer. She first began making comics at the age of 18 and created the viral webcomic Qahera, a satirical superhero strip starring a visibly Muslim superheroine.

Shubeik Lubeik is a must read for all who enjoy satirical works about social injustice and corruption such as Noviolet Bulawayo’s Glory and Niq Mhlongo’s For You, I’d Steal a Goat!

***

Buy Shubeik Lubeik: Penguin Random House (US) | Amazon (US) | Amazon (UK)

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions