Introduction

Sindi-Leigh McBride & Julia Rensing

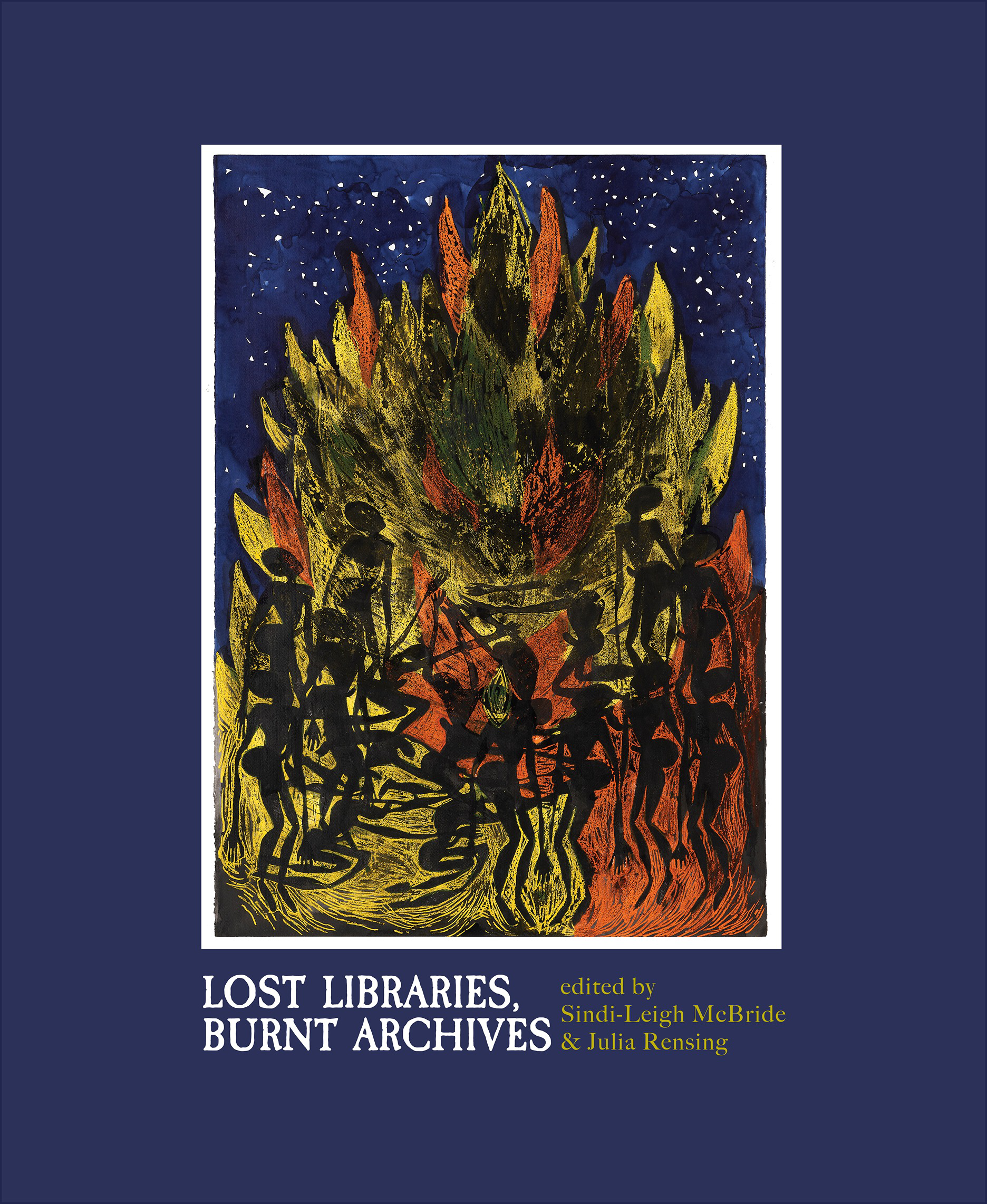

Lost Libraries, Burnt Archives contemplates what surfaces when a library is burnt, an archive lost, and what emerges from the ashes and ruins. As African Studies scholars attuned to the gravitas of the University of Cape Town’s Special Collections, we were horrified by the loss of the Jagger Library to wildfire on 18 April 2021. Constructed in the 1930s, the Jagger Library originally served as the main library of the University of Cape Town but, at the time of the fire, was home to the Special Collections department which included the significant African Studies collections of published monographs and pamphlets, as well as a rare book collection, several specialist collections, and one of the largest African film collections in the world. We watched the blaze online from Basel, Switzerland, aggrieved for the implications of this loss, not only for the university and its community but for African Studies in general. As professor of International Economic Relations Adebayo Olukoshi succinctly puts it, “African Studies outside Africa has generally enjoyed better resource endowments than African Studies in Africa itself.”¹ For an African institution to no longer hold the wealth of knowledge resources that UCT Libraries Special Collections represented is both epistemically and politically devastating.

We later discovered that Duane Jethro and Jade Nair would be curating a commemorative exhibition and were really interested in learning more about their work through an active and inclusive learning approach that involved others. Of Smoke and Ash: The Jagger Library Memorial Exhibition is a collaborative project between the Centre for Curating the Archive, Michaelis Galleries, and the University of Cape Town Libraries. The public exhibition aimed to simultaneously memorialise the loss of the UCT Jagger Library building and its archive and celebrate UCT librarians and volunteers who participated in the salvage operations that followed. In their curatorial statement, Jethro and Nair explain: “We pay homage to the grief by creating a curatorial space evocative of the smoky, chaotic textures of the disaster. The exhibition is itself a salvage project.”² At the Michaelis Galleries, situated on UCT’s Hiddingh campus, a faintly singed smell permeated the materials gathered by the curators. Charred books and other found objects from the Jagger Library site were presented together with images and texts contributed by volunteers, artworks created by graduate students from the Michaelis School of Fine Art, and UCT’s own documentary record of the Salvage Process.

This publication takes its cue from how Jethro and Nair used exhibition-making as a medium to make sense of the tragedy, not only to mourn what is lost and celebrate the salvage efforts but also to expand how the event was understood. In our own work, we have been similarly interested in thinking about avenues to broaden approaches to knowledge production in African Studies. Like Jethro and Nair, we are committed to pursuing, in professor of Literary and Cultural Studies Pumla Dineo Gqola’s words, “new ways in which meaning might be further harnessed by placing the creative and the explicitly critical alongside one another.”³ In that spirit, we reached out to the curators, designed a workshop for collective engagement with the exhibition, and invited a group of artists and academics interested in archives, art history, and other related topics.

The workshop took place in April 2022, exactly a year after the tragedy, and began with a guided tour of the gutted interior of the Jagger Library, led by Geographic Information Systems (GIS) specialist Thomas Slingsby that proved to be both informative and emotional.⁴ This was followed by an exhibition walkthrough by the curators and a deep listening session by DJ and writer Atiyyah Khan. She reflects on this in her essay, ‘Lamentations of Fire’, which includes a QR code that links to her impeccable set and can be listened to as a powerful sonic accompaniment while reading the book.

The perspectives presented emerge from an array of practices – photography, fiction, curatorship, and fine arts – as well as from different academic disciplines. In varied ways, contributors explore the complex layers of meaning connected to the fire at the Jagger Library. Jethro and Nair offer personal and professional reflections on the experience of engaging with the process of making sense of the destruction. In an interview, photographer Lerato Maduna shares insights into the emotional aspects of documenting the aftermath of the disaster and how this deepened her own artistic practice.

In many of the contributions, the issue of loss is evocatively explored without descending into gloom, for example, in Sophie Cope’s pairing of personal musings on loss and damaged astronomical charts salvaged from the Jagger Library. In her interview with artist Lady Skollie, who contributed the striking cover art for this publication, Danielle Bowler asks the questions, “How do you quantify loss?” and, “What is it, precisely, that has been lost?” Short stories by Sindi-Leigh McBride and Masande Ntshanga respond to these questions and “construct an archaeology of absences”, reminding us of the potential and limits of what may be gained from absent presences.⁵ Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja, meanwhile, prompts a shift in attention to the regenerative opportunities of queer fire – understood as “an expression that moves queer bodies to make themselves and their labour visible” – in his reading of a performance by artist Qondiswa James, The Fire This Time (2022).

Reflective essays by Lorena Rizzo and Julia Rensing explore what remains after destruction, what we believe to be ‘saving’ from ruins, and how these questions relate to the concept of the archive. Carine Zaayman also reflects on the ashes left behind and what they tell us about “the hierarchies instantiated by archives”, while Portia Malatjie turns to South African artistic practices “to account for different forms of knowledge-production, conservation and dissemination.”

Transferring these considerations to other fires and other libraries, Nisha Merit interviews artist Ofri Cnaani about her work in response to the 2018 fire at Brazil’s National Museum, while Dag Henrichsen offers an epistolary perspective on the 2000 fire at the Basler Afrika Bibliographien in Basel, Switzerland. The more daunting dimensions of fire as an elemental force are evoked in the photo-essays by Eugene van der Merwe and Nicola Brandt who simultaneously engage complex ecocritical questions that arise when fires blaze at sites of colonial conquest. Ruth Sacks similarly reflects on the material and visual legacies surfacing from archives that speak to the violent reverberations of colonial projects.

There are contributions that urge thinking beyond the fire, the university, the archive: Bongani Kona shares a nuanced mediation on memory, while Niren Tolsi braves both the “fires of rage” and the horrors of lives lost to the ever-burning flames of global xenophobia. A smouldering poem by Koleka Putuma reminds us that, though “we have been intimate with fires for too long”, we remain in need of new ways of reading fires, libraries, and archives, which resonates strongly with Zanele Muholi’s important assertion that “the archive means we are counted in history.”⁶ Iconic photographs by Santu Mofokeng are proof of just how true this statement is. For us, this creative publication is an attempt to expand knowledge production practices in African Studies, questioning not only who is included in libraries and archives but also how the ‘knowledge’ of these realities and related epistemic injustices emerge.

Akin to how the curators salvaged and commemorated, the contributions gathered here similarly parse through the old and assemble myriad new ways of knowing. In a way, this book, emerging from the ashes of many other books, is a response to a lost archive and a contribution to a new one in the making.

Finally, on the practicalities of book development: a limited print run inadvertently resulted in a forced intentionality about how this book is distributed, bringing to head the injustice of limited access to creative publications in South Africa. As such, the book was not made available for sale and instead distributed throughout and beyond university environments to public libraries, research institutions, and specialised archives throughout the country and beyond.

******

¹ Adebayo Olukoshi, ‘African Scholars and African Studies’, Development in Practice 16, no. 6 (November 2006): 540.

² Duane Jethro and Jade Nair, ‘Curatorial Statement: Of Smoke and Ash: The Jagger Library Memorial Exhibition‘, University of Cape Town, accessed 8 January 2023, https://ibali.uct.ac.za/s/of-smoke-andash/page/curatorial-statement

³ Pumla Dineo Gqola, ‘Whirling worlds? Women’s poetry, feminist imagination and contemporary South African publics’, Scrutiny2 16, no. 2 (2011): 5.

⁴ A panorama tour of the Jagger Reading Room after the fire is accessible online at https://ibalimanifest. uct.ac.za/jagger/

⁵ Martin Hall, ‘People in a Changing Urban Landscape: Excavating Cape Town’, Inaugural Lecture, University of Cape Town, 25 March 1992. Cited in Gabeba Baderoon, ‘Oblique figures: representations of Islam in South African media and culture’, PhD dissertation (University of Cape Town, 2004), https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/7965

⁶ Muholi quoted in Suyin Haynes, ‘”The Archive Means We Are Counted in History.” Zanele Muholi on Documenting Black, Queer Life in South Africa,’ Time, 3 December 2020, https://time.com/5917436/ zanele-muholi/

*****

Read the full excerpt and download for free here: Lost Libraries, Burnt Archives PDF

Excerpt from LOST LIBRARIES, BURNT ARCHIVES published by University of Cape Town and Michaelis Galleries. Copyright © 2023 by Sindi-Leigh McBride and Julia Rensing.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions