Americanah first came to me in high school, two years before my undergraduate years in the American Midwest began, and two years until I too began my journey at nineteen of becoming an ‘Americanah’. Reading it at my international high school in India meant that I could apply my newly acquired skills of textual analysis as I’d done before with the works of Blake and Nabokov and Malouf. Immediately, I had identified with Ifemelu, the novel’s protagonist, for her forthrightness, worldview, and black hair politics that textual analysis went out the window. And what glory it was to be the only West African girl in that class, to be able to attest to Adichie’s spot-on selection of Bracket’s Yori Yori song for the telling of a rekindled love story, a song that had been on repeat the previous year at my mother’s birthday party at home in Freetown (544). My first copy of Americanah sits on my bookshelves in Freetown, while I carry a copy with my many annotations from my undergraduate dorm room to the apartment I now share as a student in my MFA Creative Writing program in Texas.

Recently a fellow West African student said to me, “Recall how well Adichie’s characters land on the page. Aim to write like you know your characters, like you’ve truly met them.” I had not paid rapt attention during my first and second reads of Americanah to just how numerous the characters were. I remembered from that first read, however, that the reader immediately feels a keen sense of familiarity with the characters. It is in the way, regardless of ethnicity, we may know an Aunty Uju who is subject to the whims of men she settles for, or Ifemelu’s mother’s blinding spirituality, or that Curt, for all his sensitivity and thoughtfulness, would never truly understand the nuance of what it means to be black in America. Adichie’s characters are people we’ve met and interacted with, yet they are distinct and poised with purpose on the page. It is also Adichie’s characterization that seems to receive the most critique. One classmate during a conversation where we swooned over Adichie’s mastery of craft and characterization had said with a smirk that “Adichie made her characters do all her dirty work.” Online reviews often question too what became of Ifemelu and Obinze at the end or what we are to glean from Ifemelu’s last words to Obinze in the text. Do they make it official, again?

Americanah continues to sneak up in conversations at my MFA program as every now and then we fall into the trap of comparing new African novels to it and postulating new theories of where exactly Adichie’s genius lies. It slips into conversations with professors and random fiction enthusiasts who on seeing that I’m black and African assume (and rightly so) that I have read and love Adichie’s work, who also go on to point out things that stood out to them when they read her.

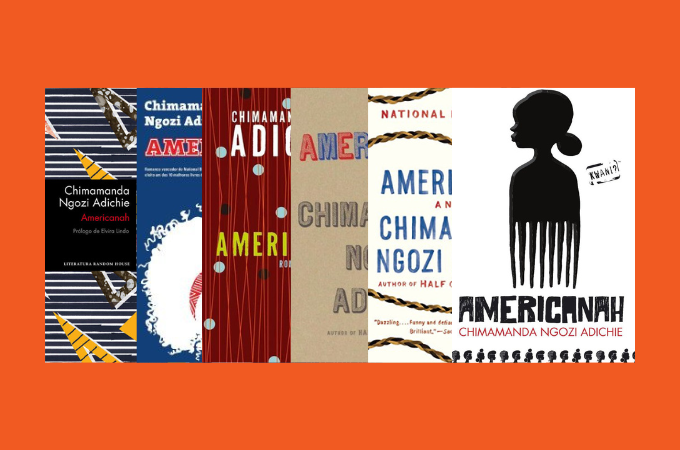

I now think of Americanah as the modern-day immigrant tale that critiques social standards. Adichie’s novel has permitted budding African storytellers to attempt similarly ambitious literary projects thus birthing the myriad debut African and diasporic African novels with bright covers that promise varying levels of focus on the African immigrant experience.

In my personal life, I have been fascinated by the various ways that the almost 600-page masterpiece continues to haunt me. It is how like Ifemelu and Obinze, a young man I’d met in high school back home soon became a geographically challenged ex-lover or the nervousness I felt when I first heard that there would be a screen adaptation of Americanah. I had replayed the concept trailers and doubted some choices when potential characters did not match how I’d pictured them and then I followed the debates that ensued on social media about these choices all the while wondering how one novel could cause such traffic.

I wish to one day write a novel as wholesome and haunting as Americanah. I wish to imagine and develop a plot and premise just as strong. I look to Americanah and other works like it to feed my understanding of what is possible and of the profound ways that characters and cultures can interact on the page.

In the meantime, while conversations about the woes of the African state (as exemplified by Nigeria in the novel) remain; and while issues of racial tensions ebb and flow in America, Americanah remains steadfast for me in its ability to haunt and teach and surprise me with each read. And then the question of what becomes of Ifemelu and Obinze at the end of the story has always been a simple one for me and it is this: the pair do not remain bound in two-dimensional print or fall off the page into oblivion. Like Adichie’s other characters, they live on while we remain trapped as hopeless romantics, forever remembering the pages that introduced them to us.

Joe April 07, 2023 13:37

Congratulations on your wonderful creative presentation, am proud of you keep moving surely they sky is your limit. I wish you well