Introduction

– Makhosazana Xaba

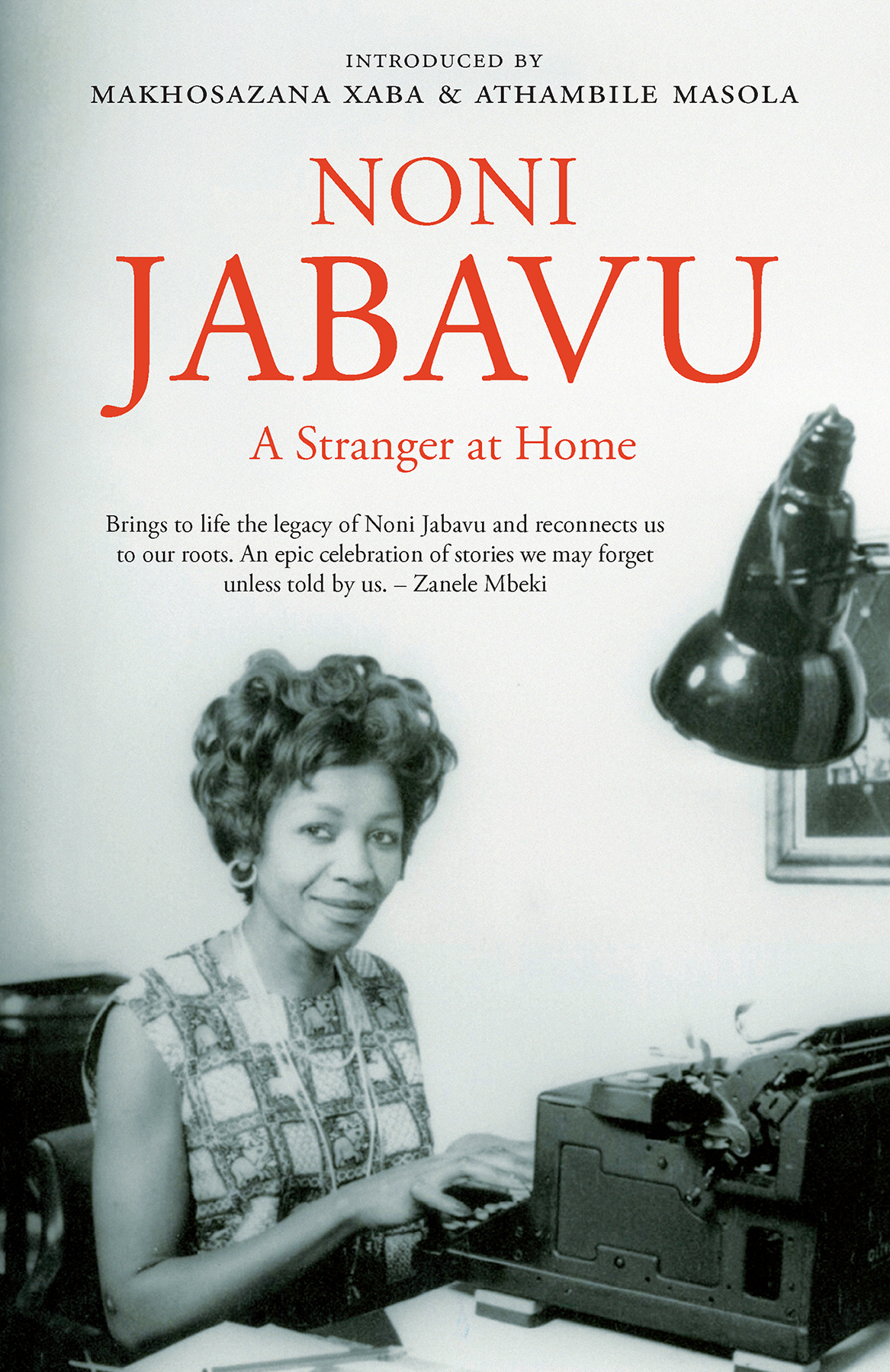

This book is a compilation of columns written by Helen Nontando (Noni) Jabavu for the Daily Dispatch newspaper in East London in 1977. It is a significant slice of history and a project against the erasure and flattening of Black women’s identities. Noni’s writerly identity – one of many she had – is remarkable, considering the way women were often presented in public discourse during her lifetime.

Society’s need to see women through narrow, confining lenses and roles as mothers, wives and carers/nurturers has been shifting over the decades as women have been adamant in claiming and owning their wholesome and complex selves. Noni’s books, Drawn in Colour: African Contrasts (1960) and The Ochre People: Scenes from a South African Life (1963), were published by John Murray in London and St Martin’s Press in New York. An Italian translation of Drawn in Colour came out in 1962 in Italy. Noni was a memoirist of the 1960s, becoming the first Black South African woman to publish memoirs. She also became the first Black person, the first woman and the first person born outside Britain to edit The New Strand, a literary magazine. She edited five issues at the magazine’s London office from December 1961 to April 1962, at which point she moved to Jamaica. The Daily Dispatch columns are the first of her writings that were published in South Africa, making her work readily available to the South African reader. The Ochre People was later reissued in 1982 by South African publisher Ravan Press.

Who were Noni’s peers in the South Africa of the 1960s, when she was editing The New Strand magazine? Nicolette Ferreira provides a useful entry point. In Grace and the Townships Housewife: Excavating South African Black women’s magazines from the 1960s, Ferreira notes:

Between 1965 and 1969, most politically orientated magazines produced by the Black press in South Africa were silenced as a result of apartheid’s restrictive measures. This was, however, a time when Black women’s magazines could become more prominent, as they were viewed by the apartheid government authorities as apolitical and thus less of a threat to their political agenda.

The 1960s witnessed the birth of two magazines: Grace (October 1964–December 1966) and The Townships Housewife (February 1968–April 1969), which ‘appear to be the first women’s magazines in South Africa aimed specifically at Black women’.

The women who wrote for these magazines were Noni’s peers, in her country of birth. Although both magazines were whiteowned and driven by profit, they constituted a platform where ‘African women express[ed] their needs and aspirations’. Interestingly, there was a letters page in Grace entitled ‘I write what I like’; readers wrote whatever they wanted to say which ‘creates a platform for us to start considering the link between Grace and the awakening of Black Consciousness in the early 1960s’. The list of Black women’s names continues to point to the need to excavate more writings by Black women, and to demonstrate that the male domination of the Black press in the 1950s and 1960s was not left unchallenged. In one of the chapters, Ferreira makes the following conclusion:

In contrast, then, the ‘backward’ depiction of Black South Africans in white magazines such as Die Huisgenoot, Sarie Marais and Fair Lady, Black women in Grace and The Townships Housewife are young, modern, beautiful and glamorous. Grace and The Townships Housewife challenge the representation of Black women in white women’s magazines, while simultaneously disturbing the representation of Black women by a mostly male magazine staff during the preceding Drum decade.

One wonders, did Noni ever read these two magazines? Did any of these writers know about and read Noni’s books? More specifically, did Patience Khumalo, the editor of The Townships Housewife, ever read Noni Jabavu, the editor of The New Strand magazine, and vice versa? Knowing as we do that the deepening and systematic entrenchment of apartheid created walls between people, it is possible that the answer to these questions is a categorical ‘no’. That said, it is also possible that the answer is a categorical ‘yes’ because the written word has the capacity to travel: it can create holes through concrete walls, cross bridges, swim up and down river streams, climb mountains and fly over borders to faraway lands. The written word can be unstoppable.

Patience Khumalo, like Noni, was a pioneer in her editorship of The Townships Housewife:

Patience Khumalo, Black ‘editress’ of The Townships Housewife, deserves acknowledgement for her position as Black female editor of a magazine for women – not even popular Afrikaans women’s magazine, Sarie Marais, had a female editor until 1994.

Grace was the brainchild of Mrs Esther K Nyembezi, who wanted to challenge the way Black women were written about by Black men and white people. The list of names Ferreira excavated through her invaluable research on the two magazines for Black women by Black women deserves a spotlight in this introduction:

Women who penned stories and articles for these two magazines, such as Zebediela Malifi (in The Townships Housewife), Mrs IG Buthelezi, Thandi Zulu, Molly Moreni, Kathleen Mkwanazi, Jo Simpi, Candy Mtetwe, Likhwa CW Mpofu, T Dmbithula, Eileen Sithole, Fato Ngobele and Violet Xolo (in Grace), deserve recognition for being part of this new decade of women’s magazines.

In 2019, Noni would have turned 100 years old. Born on 20 August 1919, she died on Wednesday 18 June 2008. A few days earlier on a Sunday, I had shared my Noni biography project and journey on a panel called The Role of Biography in Understanding Our Pasts. Noni’s columns also do the same kind of work – they help us understand our pasts; nomadic, writerly and otherworldly. Her columns were written in a decidedly personal style; what she called ‘personalised journalism’. In a letter to a friend in 1978, Noni mentioned her plans to compile her columns into a book. She wanted to revise the columns slightly so that they were less casual and conversational, and instead took on a more narrative and literary tone. The publication of this book is a realisation of one of Noni’s dreams.

The Daily Dispatch newspaper was established in 1872 under the editorship of Massey Hicks. In 1977 Donald Woods, the editor, had been in this position since 1965. Noni was living in Kenya when she visited South Africa in 1976 for three months; she returned in July and stayed until December 1977. She was conducting research to write a biography of her father, Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, popularly known as DDT. Her first column reflects on her experience upon arrival at the airport; how the immigration officers had not believed she was a British citizen. And her retort, ‘I became British in my own right in 1933,’ had not made her situation easier. This airport experience became her reintroduction to occupying the position of a perpetual suspect, an undesirable, a nuisance and a loud-speaking, know-it-all native. Racism was however not the only challenge that Black women had to face daily. Black men, sometimes in cahoots with white men because of their patriarchal beliefs, were also a hindrance, a marginalising force and perpetrators of women’s oppression. Women lived this reality daily, long before the currently fashionable use of the concept ‘intersectionality’ became a quotable in conversations on feminism.

***

Buy A Stranger at Home: Amazon

Excerpt from A STRANGER AT HOME published by Tafelberg, an imprint of NB Publishers. Copyright © 2023 by Noni Jabavu, Makhosazana Xaba, and Athambile Masola.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions