In the fall of 2022, a friend of mine suggested I go see a private antique collection in Asmara owned by a man named Fitsum Ghebreselassie. By that point, I had already heard a few mentions of Fitsum’s collection but had never had the chance to visit, so naturally, I agreed.

You’d imagine that a private collection of this sort would be stored somewhere regal; one could even imagine a mansion or a museum. But the reality was quite different. Fitsum is the owner of Jumbo Glass, a glass manufacturing company in Eritrea, and the collection is kept in one of his warehouses. The warehouse is located near a lime factory in Asmara known locally as Enda Nora, tucked to the right side of a narrow road just off a busy street. It isn’t the kind of space that grabs your attention from afar, not a single hint of what lies in store. This struck me as ironic, considering how such an ordinary-looking place is anything but.

I walked through the gate towards a small room filled with beautifully designed mirrors where I was warmly received by his sister. Fitsum walked in right after me, on his way back from a business meeting. His large frame dressed in a burgundy pullover, black trousers and black oxfords, his round, moustached face and his booming baritone voice seemed a bit intimidating at first, but his friendly demeanor soon made me feel at ease. We exchanged a few pleasantries as he motioned for me to follow him into his office, and what I found there was beyond anything I had expected.

The walls of his office were covered in wooden and glass shelves, posters and vinyl records of famous Eritrean singers – household names like Teberh Tesfahuney, Ateweberhan Segid and Alamin Abdeletif from various decades of the 20th century. Old promotional flyers inviting the public to nightclubs and concerts (“Entrance fee is 2 Birr but ladies are welcome to enter for free!”) that date back to the 1960s were on display, as were rows upon rows of black-and-white pictures and postcards of Eritrea during the Italian occupation; images of Eritrean landmarks at the time they were built next to images of those buildings today. Almost every inch of the mahogany desk at the center of the room was covered in books and documents, and even more of them were piled on the shelves in the surrounding walls.

These weren’t just any books though. I was looking at rare first editions like Il Diario Eritreo, four volumes of Ferdinando Martini, the once governor of Italian Eritrea’s, diary. Military maps of East Africa labeled in Italian were on display, no doubt used by Italian generals to plan colonial expansions. Laying open in a far corner was a large book of blueprints of the railroad system built by the Italians between 1887 and 1932. Anywhere I turned my head, I found something fascinating that only a moment before, I hadn’t the faintest idea existed.

“How did you start collecting all this?” I asked, not taking my eyes off of my surroundings.

He took a few minutes to answer, “I suppose I always had a passion for antiques, but I remember the day I started collecting. It was 1980, and I was just 12 years old. I saw an American man buying a vintage Moto Guzzi from this older Eritrean gentleman I knew and the American was saying that he was going to take it with him to the States. That experience stirred within me an urge to protect that motorcycle – and all our antiques for that matter – from being taken away. Alas, I was too young to actually do anything about it, and the man ended up taking it away with him, but ever since that day, I felt a sense of duty to make sure that more people don’t just come and chip away all these valuables to then keep for themselves, far away from where they belong. That year, I was working in a boutique part-time, after school hours, and scraped together two months’ worth of my salary to buy my very first antique: a radio.”

I started walking along the walls, reading old newspaper articles encased in frames. Fitsum walked alongside me, offering me explanations as we went.

“You see this here?” he said, well acquainted with every item’s history, pointing at the largest frame, about half my height. “This is Proclamation number 104 or Proclamazione Centoquattro in Italian, as it was more commonly known back then, that the British Administration issued in 1949 which gave them the right to exercise capital punishment as they saw fit. Do you know the bus station on Fangaga Street in Edaga Hamus? That place was once used by the British as a center for public hangings in Asmara.” His demeanor became melancholic as he uttered, almost to himself, “So many untold stories, so much suffering inflicted on the Eritrean people.”

We moved on towards his desk, where a very old mechanical calculator (what I later found out was an Odhner Arithmometer) lay. He proceeded to demonstrate how the Arithmometer works, in fluid movements that proved his proficiency.

When I remarked how knowledgeable he seemed about his items, he smiled and said, “Every object in this room, every single one that I’ve collected so far, I’ve made a point of studying: what it does, what model it is, how it works, where it was built. Everything I can think of, really,” he shrugged as he continued, “Obviously, it takes hard work and dedication, considering how many things I’ve collected over the years, but it’s a passion of mine.” He then led me to another door in his office, opposite his desk, above which were written the words, “ሕማቕ ሰብ ኣይትርአ፡ ዓለም ብግዱሳት ኢያ ትነብር” (“Don’t mind the indolent; the world is built by the bold”) and opened it to reveal the inside of the warehouse, with a collection so rich I was momentarily rendered speechless.

The walls of the warehouse were covered with several rows of shelves, cupboards and tables, each one overflowing with more objects than I can even list. Right next to the entrance was a wooden table with a glass cover, and in it, a display of every single coin ever used in Eritrea: the Austrian Talleri di Maria Teresa (courtesy of the Italians) that date back to 1869, the Italian Umberto Primo’s of 1891, the subsequent Lire (both di Regno and Fascista), the East African Shilling from British occupation, the coins used during Emperor Haile Selassie’s reign and those used by Mengistu Haile Mariam’s Dergue regime; all of which were placed at the center in chronological order. The edges of the table, on the other hand, were thickly framed with post-independence Eritrean coins, in a way that seems to engulf the outdated currency, indigenous camels, elephants and gazelles chasing away the foreign emperors, kings and queens.

Another table on the other side of the entrance had old watches on display and another still contained at least twenty different brands of matches that were made and exported from Eritrea a long time ago. One shelf held what looked like every camera that ever existed, another shelf seemed to hold every kind of antique radio: you could see the evolution of those gadgets just by looking at them. Another still contained a sample of every alcoholic beverage ever manufactured in Eritrea, from Melotti beers to Cognac “Quarantaquattro” to Zebib’s Areqi (the Eritrean equivalent of a Sambuca) and right above the display were old ads and company slogans in their original posters (“Chi beve birra Melotti campa cent’anni!” – “Those who drink Melotti beer live to be a hundred years old!”).

There was a display of several kinds of tobacco pipes produced in Eritrea during the Italian occupation and exported to countries like the US. One wall was plastered in every kind of license plate that’s been used here from the time of the very first cars to the license plates used most recently. The center of the room was taken up by a vintage cyan Torpado bicycle that looked like it came straight out of a 1940s Italian film and three cars, an off-white 1948 Fiat 1100 Bauletto, and two Fiat 508 Balillas, one ruby red manufactured in 1932 and the other, dark green from 1934.

Old VHS cassettes of famous Hollywood movies from the 20th century, and several Fidelipac cartridges used by radio stations in the 70s were stacked one on top of another, a Beatles album at the top. Traditional musical instruments that belonged to famous Eritrean musicians were carefully hung, the musicians’ old posters and vinyl records, of varying rotations per minute, exhibited next to them. Italian musician Pippo Maugeri’s 1956 famous song “Asmarina” (Girl from Asmara), in particular, was propped on a glass case, next to a photo of Maugeri and his band. I was surprised to find the 8mm, 16mm and 35mm projectors that once belonged to cinemas like Roma, Impero and Dante, the same art-deco cinemas that Asmara is known for today, and a large reel-to-reel tape recorder with old footage of the Apollo 11 splashdown, broadcast in Asmara in 1969 by the US military from their installation in Kagnew Station. On the wall adjacent to where the projectors and tape recorders sat, there were several rows of old reel films in their cylindrical cases, the kind I had only ever seen in old movies, and behind those was a larger-than-life poster of an Italian film “La Preda,” starring 1970s Eritrean movie star, Zeudi Araya.

Here, history no longer seemed like a vague recollection of the past. History lives and breathes in the rooms, the essence of the old days somehow still palpable in each item. As I stared at the objects, I couldn’t help but feel them staring back, inviting me to discover their stories: who they belonged to, where they had been, what they had “seen”.

A quick overview of the warehouse and some of the antiques in store

“Everything here tells a story of where we’ve been. They’re like footprints we left in time. Who would have remembered any of this if it weren’t here? As the saying goes, ‘Those who fail to learn the lessons of history are doomed to repeat them’. My vision with this collection is long-term; it’s about keeping our history and all of our relics intact, within our own borders, for centuries to come.” I could tell that this collection was a time capsule to him. It was his way of communicating the past with future generations, making sure that the ties between the two weren’t severed altogether. I admired how many things this man had thought to preserve; things that would have doubtlessly slipped through the cracks of time.

It can’t be an easy job, I thought to myself, and decided to ask, “What does it take to become a collector?”

Fitsum didn’t miss a beat, “There are five elements you need as a collector. I’ve already mentioned three: passion, hard work, and dedication,” he said, listing the elements on his fingers. “The fourth is patience; collecting is a very slow process, it takes a great deal of time. What you see here today took me forty-three years to collect”

“And the fifth element?”

“The fifth is money. I can’t tell you how much money I’ve spent over the years to acquire and maintain these pieces. But even though I bought everything here with my own money, I don’t consider myself their true owner. I am nothing more than a guard here, making sure everything stays in good condition. The real owners of these artefacts are the people of Eritrea.”

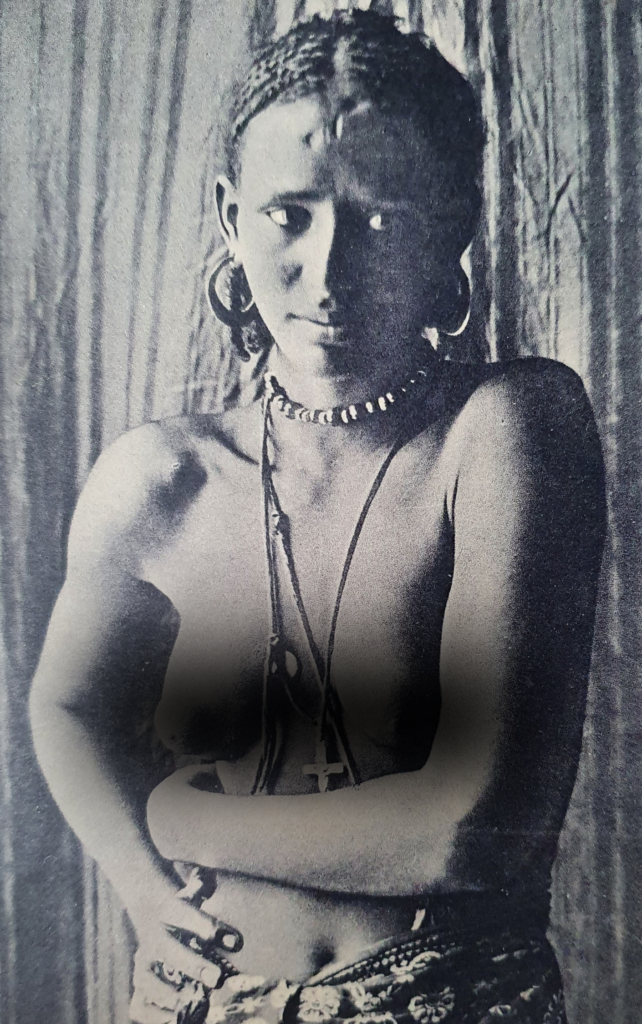

I carried on exploring the rooms, my attention jumping from one object to another at record speed. I slowly walked back towards Fitsum’s desk, and on my way found a small photo album on a countertop. As I leafed through it, I saw old black-and-white photos of Eritrean girls, no older than fifteen years, all made to pose topless in front of the camera. The photos all had labels on them in Italian – “Ragazza Indigena” – next to the year the pictures were taken.

Fitsum saw me looking at the pictures and said, “When Italy colonized Eritrea, they wanted many of their own citizens to move here, so they forcefully took degrading photos of Eritrean girls, from various ethnic groups, and used the pictures for postcards to attract potential settlers.” I felt repulsed hearing how those young girls – better described as children – were exploited and fetishized for gain, the fact that they’re human beings with thoughts and feelings completely disregarded. I stared at the girls’ haunting eyes, wondering what they must have been thinking in those moments. I could see a mix of confusion and fear on their faces, and I imagined what must it have been like, to be jerked around by a group of jeering, sleazy men, to be stripped topless and to find a strange device planted in front of you, a rude light bulb going off noisily, blinding you momentarily, catching your expression – a deer caught in headlights – all while you have no idea what is happening, what this contraption is, what they’d just done to you.

Postcard of an unsuspecting young Eritrean girl made to pose in front of a camera

Seeing the frown on my face, Fitsum commented, “We may like certain parts of our history, and we may hate others, but we can never deny any of it. Every event that’s ever transpired, good and bad, should be preserved and recorded.”

As Fitsum sat on his desk chair and I opposite him, I wondered aloud, “How much is all of this worth? Have you considered monetizing it somehow, maybe charging a small entrance fee or something?”

He gave me a knowing smile, like he’d been asked this question many times before, “We are all products of our communities. I am who I am because of my society’s contribution in raising me and teaching me. This is my way of giving back. Any personal or short-term gain I may be able to find is not of interest to me. That’s why I never intend to monetize my collection: anyone interested is more than welcome to visit free of charge. But I do hope that one day my collection will be on display in a public space, where everyone can have better access for free.”

After some moments, with the sun at its peak, I set out to leave, thanked Fitsum for his time and bade him a good day, already planning my return in the near future. Once I stepped outside the premises, I looked back at the building that earlier on had struck me as ironic for seeming so ordinary. This time, its appearance felt fitting. I noticed that the modest warehouse was much like Eritrea in that way: there’s so much more than meets the eye.

Amal January 16, 2024 07:13

You have all of my compliments on both your articles! Keep on striving!