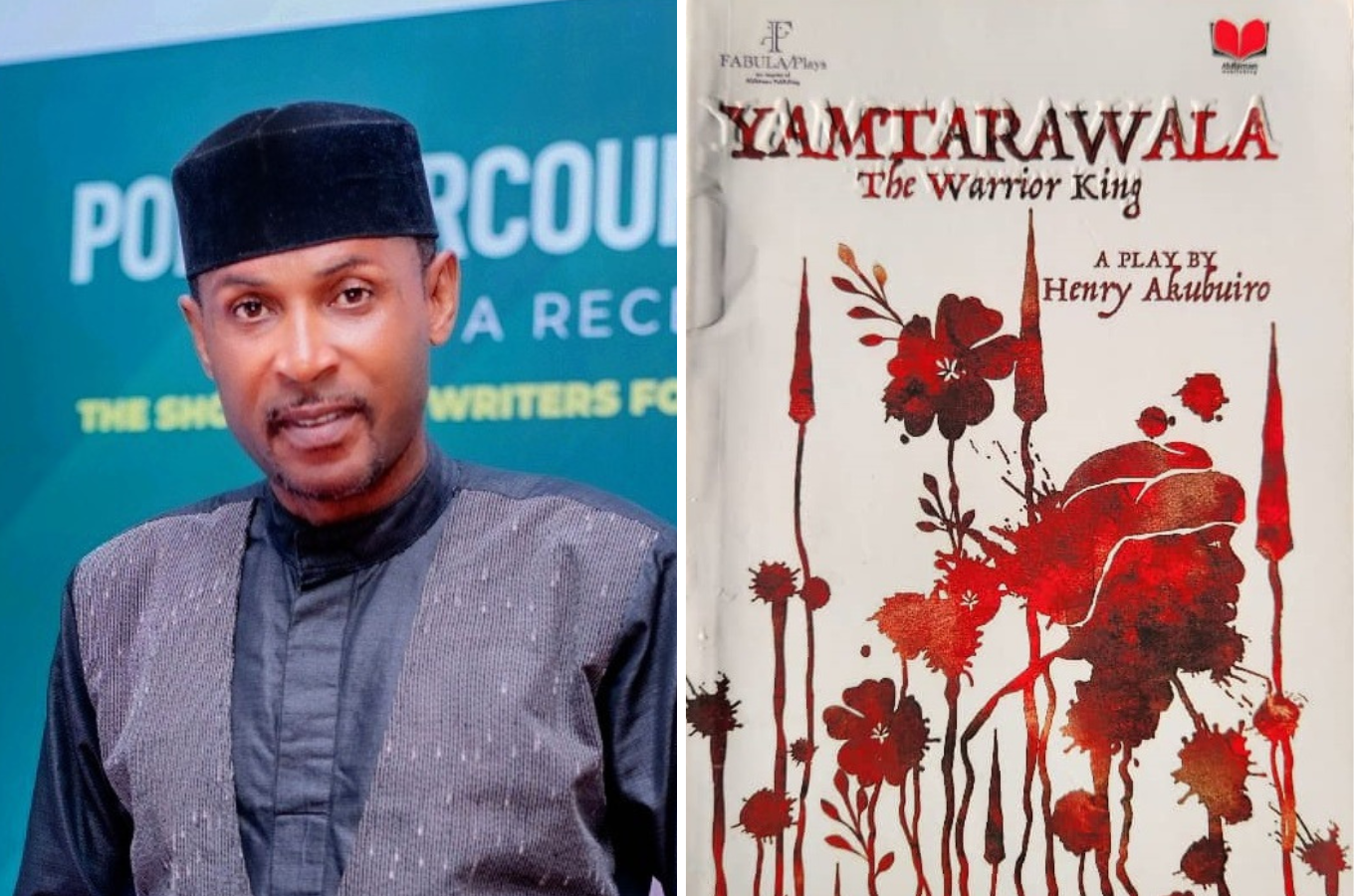

Henry Akubuiro’s play Yamtawarala, The Warrior King was recently shortlisted for the 2023 NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature. In this conversation, Darlington Chibueze Anuonye chats with Akubuiro on the inspiration and aspiration of his shortlisted book.

Published in 2023 by Fabula Plays, an imprint of Abibima Publishing, and first staged on January 28, 2023, at Rosy Arts Theatre, Owerri, Nigeria, Yamtarawala is Akubuiro’s attempt to recreate aspects of the myth of the Kanuri prince, Yamtarawala, who left Ngazargamu, the old capital of Kanem-Bornu Empire, on an empire-seeking adventure to Biu area in the 16th century. In this adaptation of the Biu myth, Yamtarawala’s travails and conquests are depicted as a symbol of all the journeys undertaken for human civilization.

Akubuiro is a Nigerian writer and journalist. He studied English and Literary Studies at Imo State University, where he began his career as a campus journalist, eventually becoming the pioneer editor of both the creative writing magazine, The Elite, and the university’s newspaper, The Imo Star. He is now the editor of The Sun Literary Review, Nigeria’s longest-running literary supplement dedicated to promoting literature.

***

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Hi, Henry. Congratulations on your Nigeria Prize for Literature shortlist. Did the news surprise you, given the number of other great plays on the initial longlist? How does it feel to be so recognized?

Henry Akubuiro

I am elated. To be shortlisted for the Nigeria Prize for Literature is a great feat for any writer, given the pool of talents in Nigeria.

I wasn’t totally surprised I made the shortlist, to be honest with you. I knew I had an uncommon story and I deliberately wrote a play meant to captivate the stage. This comes from my experience working with seasoned thespians and dramaturgs for over 17 years. Not every playwright has that kind of opportunity. The advantage of being a literary journalist is that you read new works more than most people, because writers and publishers usually send them in for reviews. So, at every point in time, you know what different writers are doing.

The practical experience I gained on the field watching stage plays and reviewing them constantly has helped me as a playwright. Whenever great plays are to be enacted in Nigeria, I am usually among the first people to be invited to cover them or watch the preview. Sometimes, too, before a play is due for preview, I am invited to watch the rehearsals. These are performances by professional thespians—members of private, state and national drama troupes. It’s one thing to be a playwright and another to write a stageable play. You could write all the beautiful poetry in a play, but if the play lacks the elements of stagecraft needed to realize it, it amounts to little. I have learnt to avoid these pitfalls. So, I wasn’t surprised when the jury said my play was not only good for the stage but for the screen. A play must be realized on stage.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

On your Author’s Note, you mentioned that Bukar Usman’s The History of Biu, which you read in 2015, was the first inspiration you had for writing Yamtawarala. And then your visits to Biu in 2016 and later in 2022 solidified your literary interest in both the mythical figure and in the people themselves. What kind of people did you meet then? Did they strike you as some of the people you met in Usman’s book?

Henry Akubuiro

Dr Usman told me recently that I have become an authority on Biu history and folklore. That’s funny. Well, I have read more than 20 books written by Dr. Usman, including folktales, myths, legends and history. Even before I travelled to Biu, I was conversant with the people and their way of life. That’s what books do to you. I have read many research works and interviews on the people.

Biu is an emirate and also the name of a town. Biu Emirate is perhaps larger than the five Eastern states put together in terms of landmass. I was privileged to tour the four local governments in the emirate. I didn’t concentrate on the towns; I went deeper into the remote villages—places a stranger would be afraid to go, meeting local people and custodians of culture. I was determined. I visited the Emir’s palace and also met the royal warriors and traders.

In all of these, I wanted to celebrate the Nigerian diversity in the play. I was also trying to revisit nation building from pre-colonial times, using Yamtarawala as a case study of how our forefathers who founded kingdoms and empires achieved that feat. The play is a reflection of that line in our national anthem: “The labour of our heroes’ past shall not be in vain.” These heroes can come from anywhere. I don’t subscribe to the literature of exclusion, where the dominant cultures are privileged over the others.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

I agree that historical fictions—whether they are prose, poetry or drama—require from the writer a connection with the source of history. But I suppose it is what the writer does with the historical deposits at their disposal that matters more in art, and differentiates literature from reportage. How did you treat the materials your research provided you?

Henry Akubuiro

I didn’t live in the world Yamtarawala lived. I relied on a historical account to write the play to unravel a complex truth, but that in itself has limitations, especially in creating scenes and dialogues. If I hadn’t travelled to Biu, I would have faltered about the setting, because I come from a different Nigerian culture. The original Yamtarawala story contained in Usman’s book served a useful purpose in the plot. There are also depictions of contemporary real-life characters in the play, just as there are fictitious ones, whom I created for the narrative. While I excerpted some expressions from the original Biu oral tradition, the dialogues of the play are mine.

Over the years, there has been campaigning for history to be restored to the school curriculum in Nigeria. We, writers, shouldn’t leave the task to the teachers alone. Achebe told us that the writer is also a teacher. So, I obeyed the clarion call of the master storyteller himself. In the play, I melded history with Indigenous artistic heritage from the Northeast.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

As a journalist, who is often interested in facts and figures, how did you negotiate the limits of facts and fiction in the play?

Henry Akubuiro

In a historical play, the playwright doesn’t pay a wholesale fidelity to the original tale, but it’s vital to retain the most important parts of the story, because you are dealing with real-life characters and a verifiable history. If you read Ola Rotimi’s Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, for instance, the play contains real-life characters and historical narratives, but not in a holistic manner. This explains why many historians hardly accept historical literature, for they see it as a distortion of reality. But a writer must balance facts and fiction. In my own case, I retained the historical account surrounding the circumstances of Yamtarawala’s birth, his conquests, obstacles and tragedy, but what the characters did in-between are a blend of fact and fiction.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Asga’s story made me think of what war does to women, how it changes their lives and makes them the ultimate casualties of history. From losing her husband to Egyptians who invaded Yemen, to being captured by Ngazargamu slavers, she is displayed as a merchandise and later bought by the King of Ngazargamu, who took her as his second wife. I’m wondering if you consciously wanted to draw attention to the historical victimhood of women.

Henry Akubuiro

Feminists have pointed this out already. Some think the societies depicted in the play have little regard for women. Societies evolve, mind you, but this play points to a moment in history when women had no control over their destinies. Yes, Asga was a Yemini slave girl put up for sale. She ended up as the queen of Yemen and, when captured by the slave raiders from Kanem-Bornu, she also became the queen of Ngazargamu by accident. Fate was cruel to her initially, but it was also destiny playing out when her fortune reversed. From a commoner, she became the queen of two empires and the mother of two kings. Her ordeals as a slave girl in Yemen and a slave in Kanem-Bornu are, indeed, sordid reminders of what women go through during war. Even in recent wars in Africa, women are raped, forcefully married out and left to roam about when their husbands and children are killed. This calls attention to the need for women to be treated much better today.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Sunnie Ododo described the language of Yamtawarala as “simple and audience friendly.” I think he meant that the language is prosaic. Does this linguistic style embody the dramaticality and the poeticism that the theatre often thrives on?

Henry Akubuiro

I guess Professor Ododo didn’t mean kindergarten language by that. He implied that the language was accessible. In modern drama, Shakespearean poetic language with metres and rhymes is almost dead. Again, no rule in drama states that the language should be totally poetic. Those conversant with my writings know I thrive on flowery language, for I am a poet, too. In fact, I have been accused of being too poetic in my novel, Prodigals in Paradise. I love painting pictures. In Yamtarawala, there is also a sprinkling of poetic language and local idioms. I deliberately avoided highfalutin words, but you would find anecdotes, proverbs and poetry in it. I think it is important that the theatre audiences understand the dialogues on stage. Amazingly, at the Rainbow Book Club reading in Port Harcourt, a few days ago, some people thought I was reading poetry when I read excerpts from the play.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Yamtawarala’s name speaks prophetically to his fate. It means, “One day, we will meet again.” And he spent the rest of his life conquering nations and people, in his desire to return to his displaced kingdom. How central is Yamtawarala’s resolve to the development of the plot of the play?

Henry Akubuiro

Yamtarawala’s trajectory as a warrior is a study in self-determination and perseverance. It’s a pointer to how the human spirit can overcome trials when rattled beyond endurance. Students of onomatology would surely find his name and the play useful, especially how Yamtarawala lived up to his name, amid the cruelty of fate.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

The narrator’s voice in Yamtawarala provides information about the past to readers. Why was it so necessary to have this omniscient character, whose role I imagine that some readers might consider intrusive, since the historical details he provides coincide with their experience of the actual moments in history?

Henry Akubuiro

The narrator plays a largely physical, informative role, rather than an invisible one. He functions to link the past with the present. Because we are dealing with a historical play, which most of us don’t know, somebody has to mediate. I have watched stage plays where people were constantly asking one another in confusion, “What’s happening here? What caused this? Why did he do this or that?” Frankly, I don’t want the audience of my play to get confused at any point. And, from my experience covering live theatre, each time the narrator appears, everybody is anxious. They want to hear something the actors on stage aren’t going to tell them. Lest I forget, experts from the National Troupe of Nigeria who saw the script at the conception stage, advised that some of the narrator’s information must be acted out. These are master thespians who have seen it all. I listened to them.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

It’s nice chatting with you, Henry.

Henry Akubuiro

Thank you so much, Darlington.

Henry September 30, 2023 09:31

Henry has done literature great service with this play