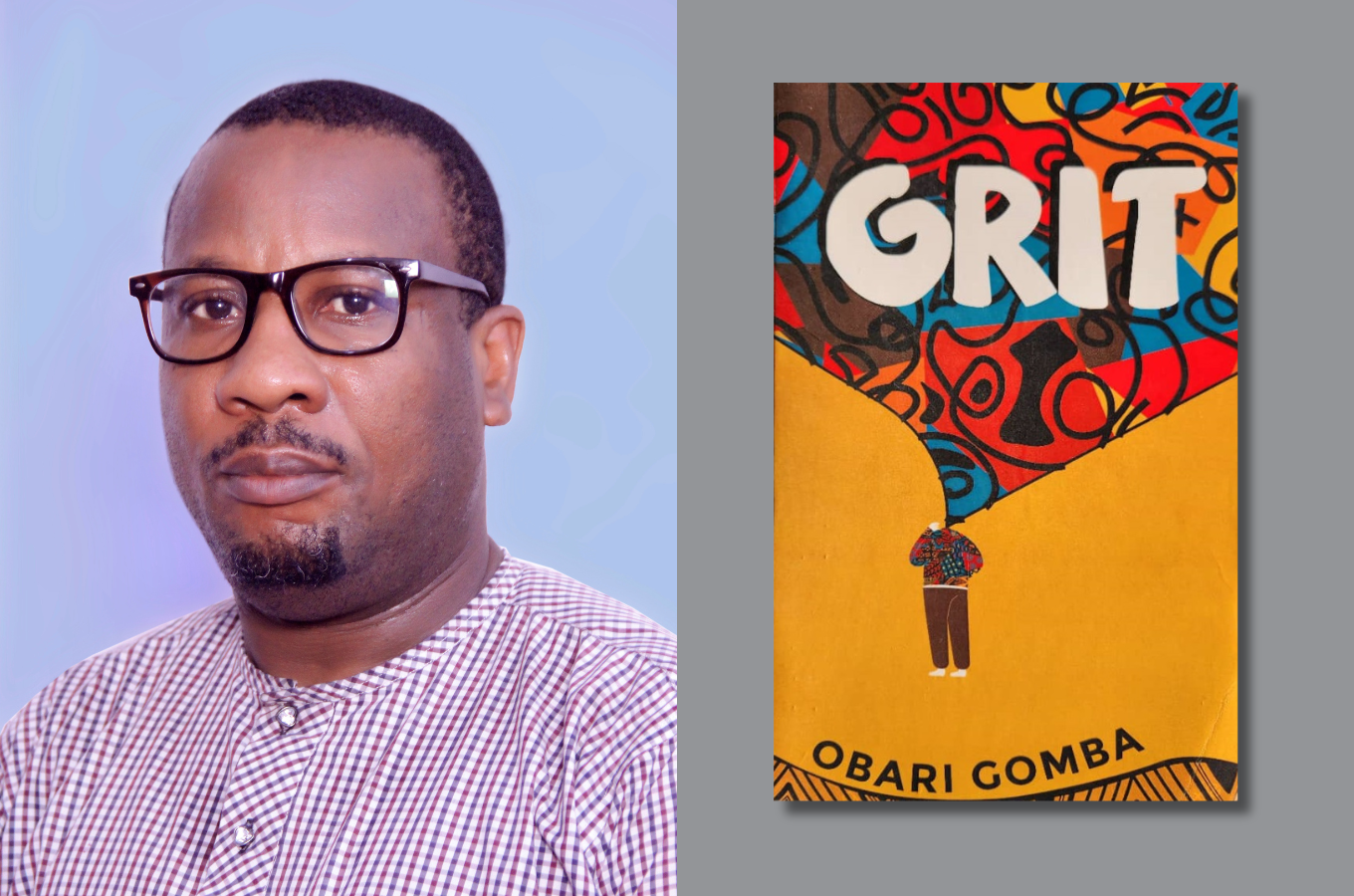

Grit by Obari Gomba is shortlisted for the 2023 Nigeria Prize for Literature.

***

In Grit, two half brothers, both ex soldiers, broken and nursing the illusion of failure, are goaded by two separate political groups to run for the office of chairman. In a twist, the two political parties end up as one with a single aim: to maim the family from the inside. The brothers are left to deal with the implications of their decisions, and the cloud of guilt and death that hovers over them.

Obari Gomba’s Grit is one of those powerful plays that leave a lasting impression. The book gives him his fifth Nigeria Prize for Literature nomination since 2013. It could win this time. Grit is compact, carefully measured, and properly sequenced. It explains what happens when a family lets itself get divided from the inside. It centralises betrayal, loyalty, grief, and service to one’s country. Pa Nyimenu’s words are central to the play’s motive: “We are beautiful with our clothes on. Without them, we bare our blemishes.” We are only as good as the image we paint of our family. The book makes it a point to admonish this from the get-go.

The play starts at the end of the story. There is chaos outside, and Pa Nyimenu, the family’s patriarch and former activist, bemoans the fate of his home. War is coming to his doorsteps and there’s little that can be undone. He is left to patch up what he can. The real tragedy of the scene becomes more profound as the story begins and we encounter what led to this.

Gomba takes a didactic route. Like many African plays, this one, too, is preachy, but it does it so well it is easy to overlook its prescriptivism. The work takes on a particular texture from the beginning and sustains it to the end. There is no affectation or missteps by the playwright. His language is strong. Suspense is sustained. Motivations are clear. The arcs settle well to a conclusive and satisfactory end.

No home is perfect, Grit cautions. There is a deep psychological nuance that overcomes a home in time. Time moves and the people with it. Mistakes are made, and there could be guilt. At the center of these is war. The war they fought in and the neglect they face in the hands of the nation they served turns them to men who believe they have nothing more significant to offer the world. Oyesllo and Okote lose their mother to the “goons of the government” during a market protest. And although Oyesllo avenges her death by killing the murderer, he turns to work for the same government. Even when he admits his plans to bring down the party from the inside when he becomes chairman, there’s enough doubt to infer he would not do so.

It is remarkable how Gomba elevates the place of women in his play. The women in the story are torchbearers. They function as active agents of reason and change in a world filled with madness. The play does not show her, but the family’s matriarch fights for fair levies for the market woman and loses her life in the process when she is shot and her corpse dragged in the market. Oyesllo’s wife, Nmade, in a rare show of foresight, sees through the antics of the women led by Matefi who convince Oyesllo to join the party to vie for chairman. Bulu, Okote’s girlfriend, is also fortified with agency as a woman in a male-dominated world.

But it would be unfair to box the play’s profile into any single tag. The work is magnificent and multifaceted in how it renders not only the damaging effects of sibling rivalry, but also how the passage of time subdues the authority of the leader of the home. Pa Nyimenu loses grip of his home and children. “What can an old man do? They are too strong,” he says, resigning to his powerlessness over his own home. Time emasculates, and the playwright paints this picture in subtle strokes. Even when Pa Nyimenu gathers his old allies to fight the enemies against his house, they fail and acknowledge that their intelligence has become “slow and poor.”

There is much value in Obari Gomba’s play. He brought me into the events and wrapped me in its closure. I became a part of the audience seeing the play in real time. It’s easy, then, to empathise with the women of Sonofa, as much as it takes no effort to understand the rationale of Bulu who refuses to bring Okote’s child into the battleground of the world. The play is that imaginative and vivid. Gomba shows himself as a skilled dramatist. He successfully delves into the lives of his characters and lets us into their world, their perception of it, and their temperament. He does this while driving the story as measuredly as possible, mounting layers and layers of grit until we finally come into the full statue. And it is such a beauty to see.

Chinaza February 21, 2024 12:12

Pls how do I get a soft copy of the Gomba's Grit. I can't seem to find it