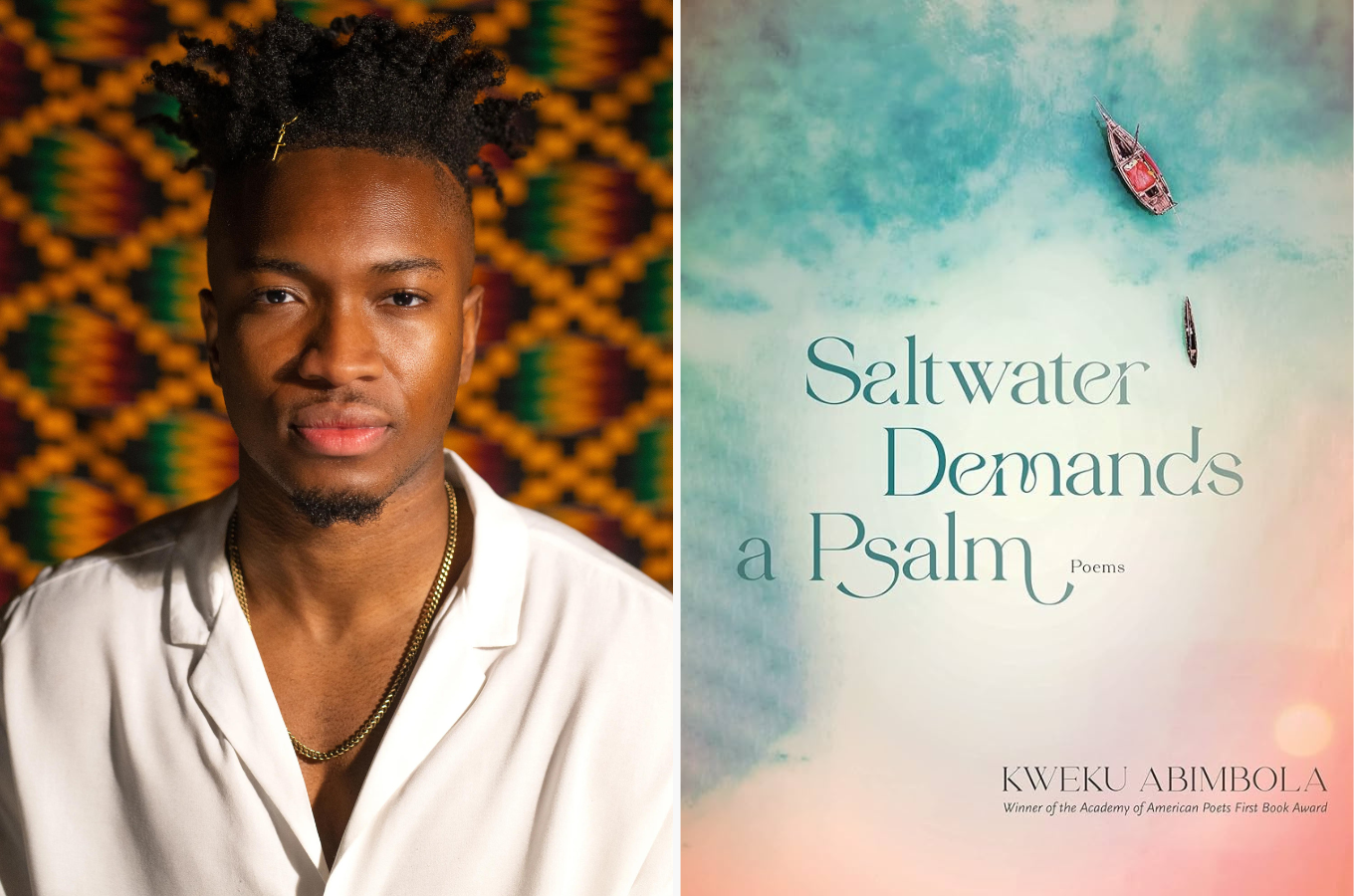

Winner of the prestigious Academy of American Poets’ First Book Award, poet Kweku Abimbola released his debut poetry collection Salwater Demands a Psalm on April 4 through Graywolf Press. Born in Gambia and of Ghanaian and Sierra Leonean descent, Abimbola draws on his ancestry to capture a stunning portrayal of Black life and possibility using Ghanaian traditions.

As the soothing title suggests, Abimbola’s debut collection is an elegy devoted to Black life and death across the decades. In 2022, Abimbola’s collection was selected by American poet Tyehimba Jess to receive the Academy of American Poets’ First Book Award. Jess praised Saltwater Demands a Psalm as “a healing, a diasporic divination, an elegy of ancestral elegance.”

Abimbola’s poetry is stunning due to the seamless way he blends Ghanaian cultural traditions with reflections on comtemporary Black life. One of the distinct traditions he presents is the Akan ritual of naming a child according to the day of the week they were born and the meanings carried inside a name. In the poem “A History of My Day”, the speaker says, “I am without a name the day/I am born.” But as the poem goes on, the speaker explains that on the eight day, his mother “speaks [his] soul name first//Kweku!/Kweku!”, attaching it to the day of the week on which he is born, Wednesday.

But Abimbola does not stop there and instead relates the intimacy of this naming practice to a series of elegies addressing Black individuals killed by police in America. While the initial odes celebrate rituals of self- and collective-care—of durags, stank faces, and dance—elegies imagine alternate lives and afterlives for those slain by police. Naming becomes a means of rebirth and reconnection following the lost understanding of time and space that accompanies Black death.

In an interview, Abimbola remarks that this intricately layered poetics of time and space is based in Black possibility:

I saw the Akan naming system as a symbol of rebirth. Even though African-Americans may not always be able to trace their ancestry as concretely as they might like, there’s a high likelihood their ancestors passed through Ghana. So, the act of assigning Akan names completes a circle, symbolizing a sort of homecoming.

He adds that his goal with this collection was to “weave together this concept of a diasporic black identity—one that’s rooted in traditional beliefs, yet malleable depending on where one finds themselves in the diaspora.” Inspired by traditional Akan dirges, the elegies invoke Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, and Tamir Rice, among others, commemorating the lives lost due to police brutality.

Abimbola’s reflections on Black death in the U.S. are deeply personal, drawn from his own experiences of being racially profiled and his journey to becoming Black:

The elegies in the book were never initially meant for publication. I started writing them as a means of healing during a time when I personally grappled with racial profiling and the fear it provoked. I was advised by a dear friend to write, but also, while navigating this violence, to avoid causing further harm to the deceased.

This personal experience drew me closer to this kind of death, a strange learning curve for Black immigrants to the U.S., who may not have been exposed to state-sanctioned or systemic racism. As someone who grew up in Gambia and Ghana, being Black wasn’t a core part of my identity until I moved here and started learning about the histories of police brutality in this country.

Abimbola said that Trayvon’s death struck him to his core as they were of similar age, and it was the first time he had witnessed racial violence depicted on TV. He added that one of the challenges he faced was the callous portrayal of Trayvon in the news that focused on his past troubles and normalized violence:

I still grapple with how these stories become normalized, and how the privacy of the victims’ families is violated. There should be agency in mourning, but that’s often taken away when people with ill intentions exploit these stories. My goal was to focus on the intimate details that fully humanize these individuals, rather than their more controversial moments.

Saltwater Demands a Psalm creates a Black cosmology inspired by Adinkra symbols—pictographs central to Ghanaian language and culture in their proverbial meanings—and rooted in units of time created from the rhythms of Black life. The visual design of the book makes the collection distinctly Ghanaian when it comes to form and is Abimbola’s “attempt to decolonize language”:

I am half Guinean and half Sierra Leonean but was born in Gambia. So, a lot of different West African cultures shape my identity. The visual aspect for ‘Saltwater’ particularly comes from my Ghanaian side. In Ghana, we have pictographs known as Adinkra symbols, which were created in the late 16th century by a king named Adinkra . . . Adinkra symbols are used as chapter breaks and even form long poems. The most difficult Adinkra symbol to create was the Sankofa, following some elegy poems in the collection. These are made up of the names of individuals who were victims of police brutality here in the U.S., shaped into the Sankofa symbol, which resembles a bird with its head looking backward. The Sankofa symbolizes memory and comes from the Akan proverb which translates to ‘It is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind.’ This focus on memory and naming attempts to honor these names in a way that is shaped beautifully but does not detract from the fact these names bear a dramatic history.”

Born in the Gambia in 1997, Kweku Abimbola earned his MFA in poetry from the University of Michigan’s Helen Zell Writers’ Program. Abimbola was a finalist for the 2021 Brunel International African Poetry Prize and the second-place winner of the Furious Flower 2020 poetry contest. He has published in Shade Literary Arts, 20.35 Africa, The Common, Obsidian, SUNU Journal, and elsewhere. He has worked as a teaching artist for the literary nonprofit Inside Out Literary Arts and lectured in English and creative writing at the University of Michigan. Abimbola is currently a visiting assistant professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Tampa.

If you are a fan of poetry that speaks to the inner complexities of Black life such as Safia Elhillo’s Girls That Never Die, then you will definitely enjoy curling up with Abimbola’s Saltwater Demands a Psalm as his soothing writing washes over your soul.

***

Buy Saltwater Demands a Psalm: Amazon (US) | Graywolf Press | Amazon (UK)

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions