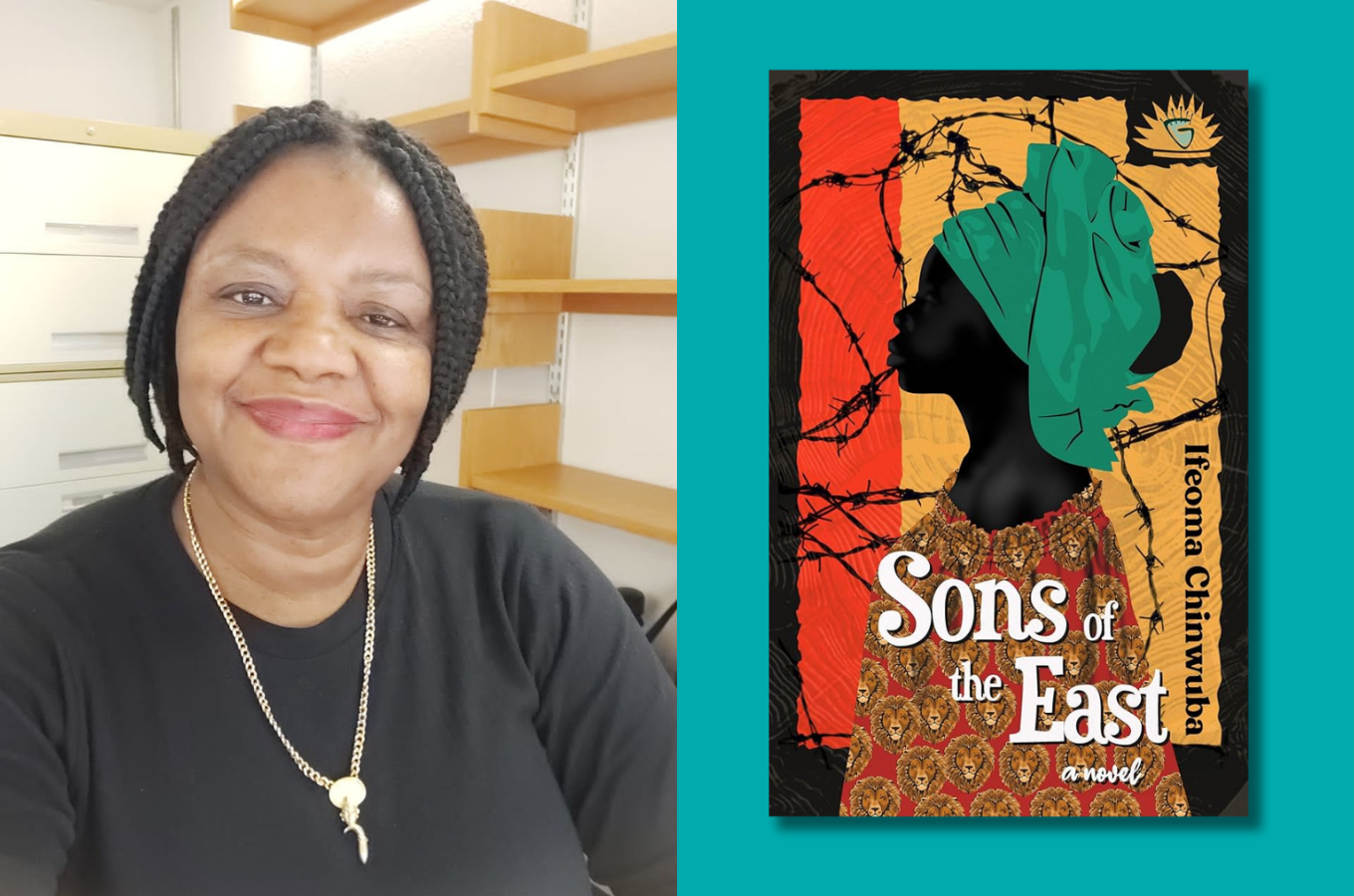

Ifeoma Chinwuba’s Sons of the East, published in 2023 by Griots Lounge, Canada, opens with the ceremony marking Jasper Okonkwo’s settlement by and freedom from his former “master,” Chief Igwilo. At the event in their hometown of Opaku, Jasper’s elder brother, Echezona, seethes with envy at the success of his younger brother. This covetousness propels the tragic essence of the novel.

Set in the Nigerian Southeastern and Southwestern states of Anambra and Lagos, respectively, Sons of the East captures one of the most important concerns of the Igbo people, which is the fact that those who live in the eastern region are incapacitated by the near dearth of thriving businesses in the region, and those who live outside the region, in Lagos and Abuja and Port Harcourt, have become rather too comfortable with the high rate of commerce and have built their firms there. Jasper voices this concern: “I do not know what we Igbos have done. We are hustling, developing towns all over the country, all over the world. Yet people hate us.” Even the three Okonkwo brothers are hesitant to return home. For instance, by the end of the novel, Rapu, like Jideofor, migrates briefly to South Africa but returns a failed merchant.

Nigerian writers have long documented this nomadic progression of Igbo sons and daughters from Igboland to spaces within or outside their country. In Jasper, we re-encounter Francis from Buchi Emecheta’s Second Class Citizen (1974), Chinonso from Chigozie Obioma’s An Orchestra of Minorities (2019), and Obi Okonkwo from Chinua Achebe’s No Longer at Ease (1960). In these works of fiction, and as depicted in Sons of the East, too, the Igbo characters bring forward their cultural ethos into more cosmopolitan spaces. There, within people who may not fully understand or know them, they keep up the communality of their trade unions, as well as maintaining their numerous mores. But most importantly, these characters migrate to seek a better life for themselves and their families. Unfortunately, they are caught in traps that impede them. These traps range from the physical, the psychological, and even the spiritual. The traps Chinwuba’s characters fall into are more spatial. Jasper and Rapu are hindered by the political forces in Lagos that target business owned by Igbo people. In the same way, Rapu’s stay in Johannesburg is cut short by the ravaging xenophobia. For the sons of the east, home is immediately where the means for survival is present.

Nigerian academic, Ndubuisi Ekekwe, traces the start of the Igbo apprenticeship system to the end of the Nigerian Civil War, when young Igbo men, disillusioned by the destruction wreaked by the war, began to leave the east to seek respite elsewhere. In 1970, right at the end of the Nigerian Civil War, the Igbos, who occupied majority of the eastern Nigerian region, were awarded a flat sum of £20. The sum, a mark of shame, issued by the Nigerian government, was disproportionate to what many of the Igbos had in their bank accounts before the war. The pittance represented, to the government, the worth of the seceding and thereafter vanquished Igbo at that time. Igbo people were required to build back from the ground they stood. How, then, were they expected to do that? Sons of the East shows how they did it. By exploring the intricacies of the Igba Boi system, an area barely explored in Nigerian literature, the book reveals to us several truths about tribalism, gender inequality, regional politics, as well as a family whose offsprings constitute the infamous sons of the east. But beyond Igba Boi, bad blood, and all associated with it, Sons of the East takes a sweep at the reluctance of most Igbo people to establish their wealth in Igboland and less in places, like Lagos, where they are not fully accepted.

While Sons of the East points towards the east and all its people, it also casts a cautionary gaze on the hyper masculinist posture that places sons above daughters. For instance, Opaku, largely patrilineal and objecting of women inheriting property, demands that Echezona produces a son to continue his line. When his wife, Charity, fails to do this, Echezona decides to take in mistresses, ending finally with Modupe, who gives him a son. It’s the old male gaze phenomenon all over again. Amata and Louisa are promised jeeps by their father if they remain virgins until marriage. Charity is considered useless when she does not give birth to a son. The family of Modupe considers itself cursed since they only give birth to female children. Chinwuba’s title is thus far from being merely a tongue-in-cheek wordplay.

What the reader most likely feels at the end of reading Sons of the East is a certain wholeness from immersion into the worldview of the Igbo people who live in Igbo land and elsewhere. But there’s more. The book, while positioning men as natural, born leaders, also deconstructs the relations between men and women, juxtaposing what makes them different, as well as highlighting the ways in which they are complementary.

Chinwuba’s tact in redressing the patriarchal conceit is laudable. She admits, by doing this, that daughters, under unique circumstances, can also become sons. In the end, what “son” may exist without the corporeality and agency of a “daughter”? To cite a few examples, Modupe’s family eases into living without their men. They are successful without men ruling over their lives and dictating their paths. The women are shrouded in their own mystery. Modupe has a daughter for an absent man. Grandma Moomie ages without a husband, and Alhaja’s husband is far away in Benin.

Family rancour, internecine disputes, and envy, manifest in Chinwuba’s book. But the novel equally teaches about the overarching power of love in creating harmony. It is remarkable how Chinwuba casts a trained eye on the very things that make up the communal life of a people. She makes an astute case for the Igbo people and their predilection for success regardless of where they may be in the world.

***

Buy Sons of the East by Ifeoma Chinwuba: Amazon

florinef bestellen legal in der Schweiz April 01, 2024 08:05

I enjoy, lead to I discovered exactly what I was taking a look for. You've ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye