“Rainmaker”

Katma and Bama were on their way to school, gliding over the blue sands of Arid on their solar-powered hoverbikes, when Katma saw the dust devils. The dust devils – two of them – were whirling around what used to be a riverbed when the deserts of the planet Arid were lush forests and grasslands. Katma’s scream of glee drew Bama’s attention to the blue dust clouds.

“Come on!” He powered down his bike, calling out to Katma. They dismounted and raced unsteadily down the wavy slip face of the dune into the valley below, which extended to the northern border of their town, Bitu. Katma had wanted the bigger dust devil and jostled with Bama to claim it. Bama, who was born off-planet but had come to appreciate the culture of the natives, did not budge and responded shove for shove until she gave up and turned to the second dust devil.

Dust devils were common in the deserts of Arid, but twin devils running side by side were a rare sight. The people who had found a home among the dunes believed they could grant a wish to anyone brave enough to stand in their path until they passed.

“What will you wish for?” Katma asked Bama as she braced herself to meet the oncoming dust devil.

Bama pretended not hear her above the roar of the wind and sand. “Mask!” he called out as he tugged his facemask downward from its perch on his forehead.

“What?” Katma asked, not hearing him, but she nodded when she saw him secure his mask and goggles over his face with the ease of long practice. Her mask was fashioned from recycled plastic and bore the likeness of a snarling cat. Unlike his which came without protection for the eyes, forcing him to combine with ski goggles, hers was a one-piece. It took only a moment for her to pull it from its resting place on her belt and clasp it over her face. “I want to see the stars!” she shouted, her voice a woosh over the roar of the twin dust devils. She hoped that telling him her wish would prompt him to tell his.

“Rain,” Bama whispered as the dust devil swallowed him.

***

The school was housed in ten large space shipping containers arranged in a semi-circle on a plateau that was halfway between Bitu, where Bama’s family settled years before, and another desert town called Awan.

Bama learnt that the committee of tribal elders that function as a government at Port Complex, the biggest town and administrative headquarters of Arid, had requested for a school building and they would provide learning materials and the teachers. The elders of Bitu and Awan, after months of arguing about the school site, finally agreed on this halfway point between the towns.

Since the school was out of town, the teachers refused to move. But they reached another compromise, to use holograms, while the teachers worked from model classrooms in Port Complex. The school now served Bitu, Awan and several nomad families scattered around the desert. Since the constantly shifting sand in Arid made building roads a waste of time, hoverbikes were the main means of transportation. As Bama and Katma flew in, there were already dozens of them in the outer curve of the containers, which the school had designated as a parking lot.

He eased his hoverbike onto the hardened earth and heard the crunch of the soft, grass-like plant under the weight of the tyres. The plant grew rapidly in the morning and withered at night, spreading spores that clung to the faintest moisture to begin the 43-hour daily life cycle all over again. In time, condensation from the cooling systems of vehicles made the vehicle park one of the few evergreen areas.

By the time Bama stored his helmet and gloves inside the storage compartment of his bike, Katma was already running towards the “official” entrance of the school, a concrete arch with a lettering that read “Bitu Nomad School”. It was erected by the government at Port Complex when they opened the school.

He ran to catch up with her. “What’s the hurry?” he asked.

“We are late,” she said.

Bama did not argue. He blamed himself for their lateness because he had taken her father’s herd of weals – the native species the Bedouin had domesticated for milk and meat – to the water dispenser and found some of the town boys there before him. He had to wait for them to fill dozens of water carts before he could key in his credits and allow the sluggish beat-up machine the first settlers had built over a hundred years ago, draw enough water to satisfy the two dozen animals in his care.

“You know, we didn’t see any other dust devils except those two,” Katma said to Bama, throwing him a look over her shoulder as she slowed down a bit.

“It’s still morning, Katma,” Bama said, “the sun will have to warm up before the wind can whip up more dust devils.”

“You don’t know that. You just like sounding smart,” Katma replied, walking faster.

Bama lengthened his stride and caught up with her as they reached the classroom.

***

“Geological records show that millions of years ago, Arid was a green planet and there were only a few deserts in her solar overlap zone,” the holographic projection of the teacher, Ms Rethabile, was saying as Bama and Katma sneaked into the class, sticking close to the wall to avoid drawing too much attention as they took their seats at the back.

“We are not yet sure what happened to its vegetation and many of the animals that fed on them, but we do know that at some point in the planet’s history, they died off. The current scientific consensus is that Arid’s desertification and the extinction of most of its lifeforms were likely due to a rare and destructive shift in its solar orbit, which triggered a series of dual solar hyper-flares. The abundance of organic matter is why the planet has so much fossil fuel deposits and a rich soil.”

Bama hated geography class, and as he was wont to do when he did not enjoy something, his mind began to wander, helped along by the lecture on soil and nutrients. His father used to talk about the soil of Arid like the teacher, only his father’s words carried more passion.

“The soil here is the best I’ve seen in any world I’ve been to. Feel the texture! How rich it smells. You’ve seen the terrariums. All we need is some water and this whole planet would be one big, beautiful garden,” his father, Basil Yadum, said to his family on the day they arrived Bitu, looking down at the town’s hundreds of brown tent homes from the dunes above it.

Bama, standing beside his father, had shut his eyes tight, knowing what came next. He struggled but failed to not hear the rest of his father’s words. Those words had brought them only misery.

“If only Amadioha would bless us again. Bless us with the rainmaking gift of our fathers.”

“I believe the blessing is still there,” Bama’s mother had offered. “Perhaps, what we lack are the tools. Getting fresh palm fronds on this planet is rare, and even if we manage to find one, will the rain gods hear our chants at all, despite being light years away from home?”

“The gods go where we go,” his father replied. “The palm fronds are props. We will call our gods with whatever is native to this planet, and they will answer. We know from experience that sometimes, they answer a little too well,” he finished in a pensive tone.

***

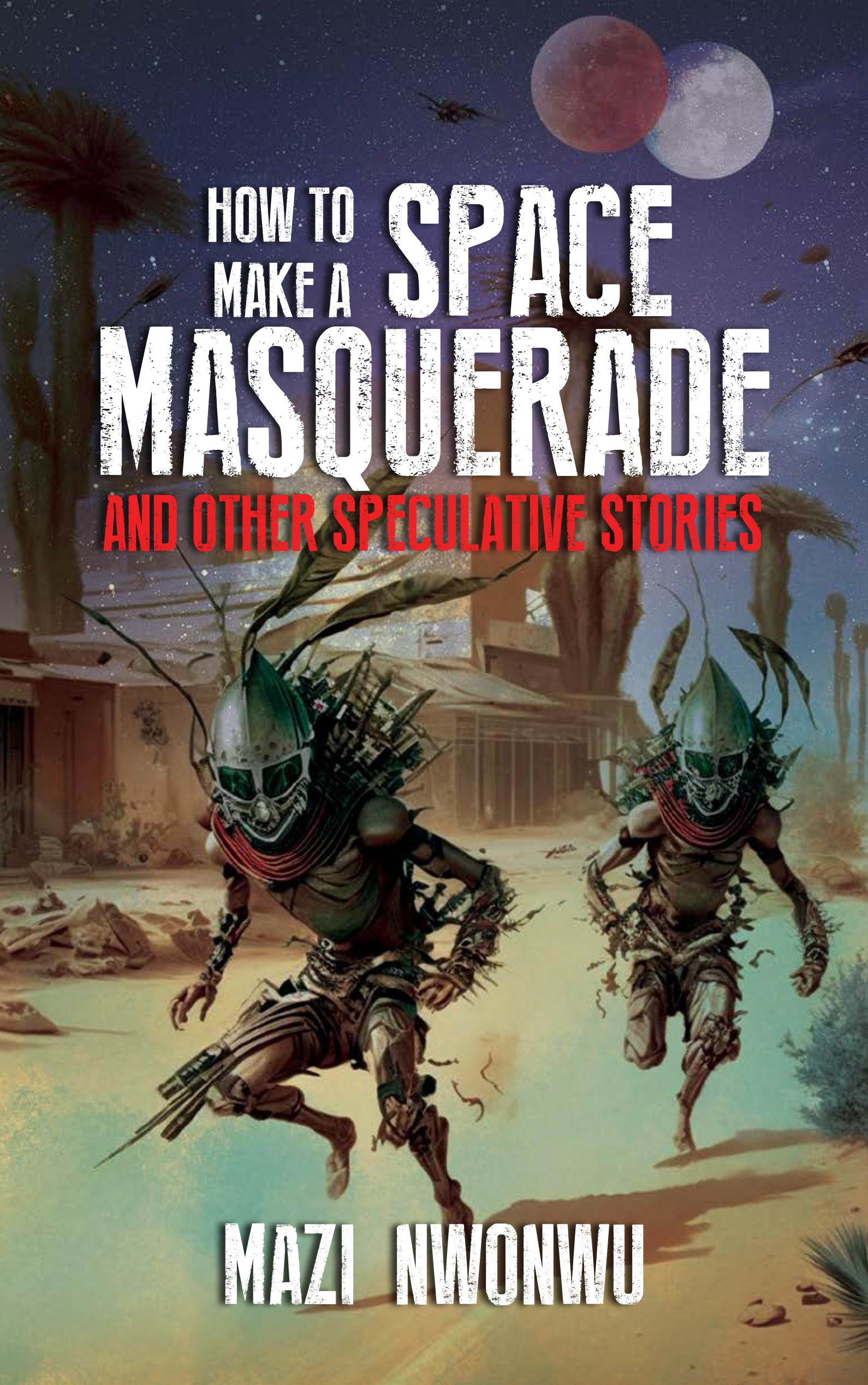

Buy How to Make a Space Masquerade here: Narrative Landscape

Excerpt from HOW TO MAKE A SPACE MASQUERADE AND OTHER SPECULATIVE STORIES published by Narrative Landscape Press. Copyright © 2024 by Mazi Nwonwu.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions