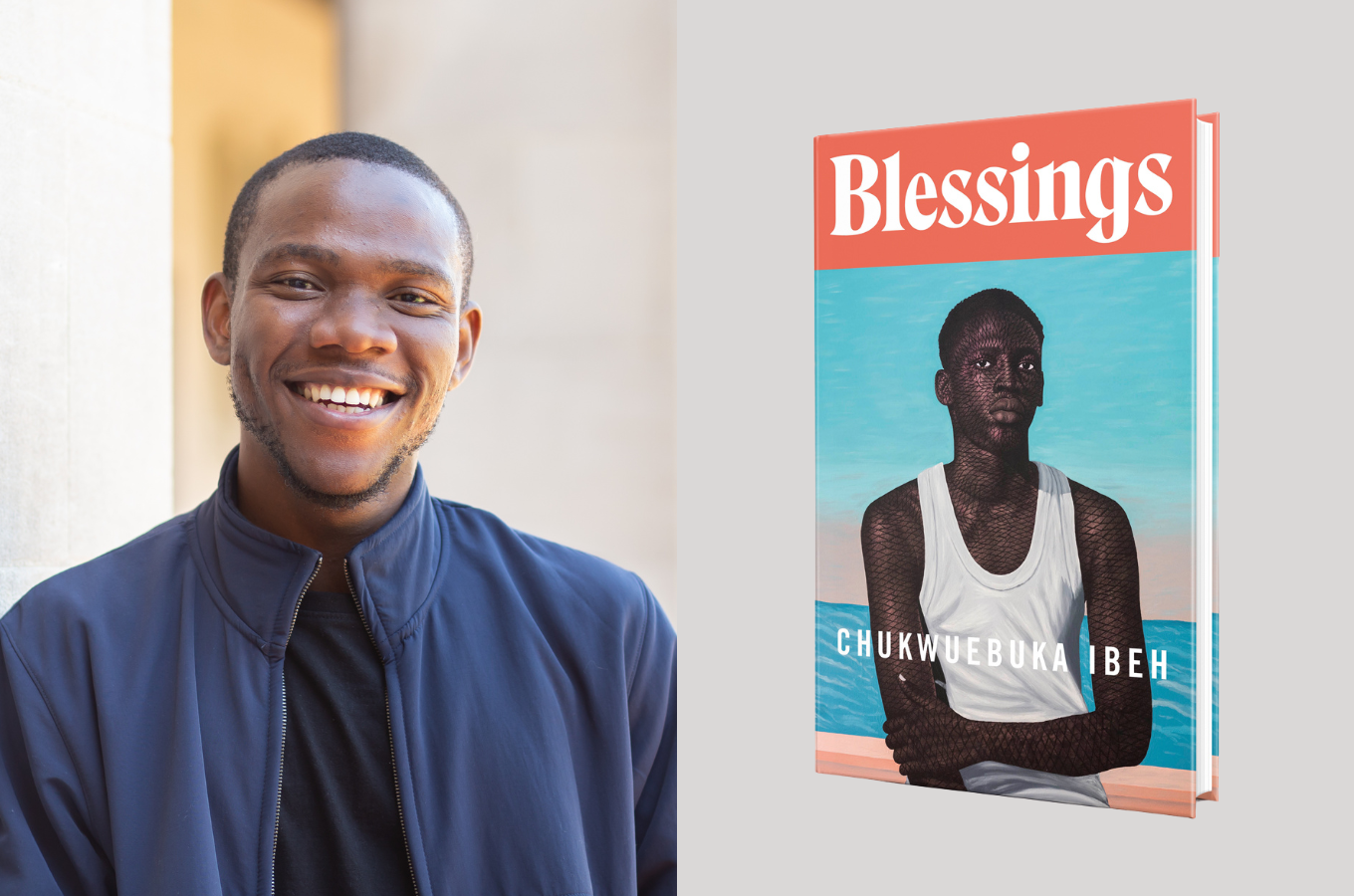

Chukwuebuka Ibeh, whose debut novel Blessings, was recently published by Vikings, was barely 14 when the antigay law was enacted in Nigeria in 2014. That Act is cruel justification of the dehumanizing condition the Nigerian state has kept its queer citizens, a daily reminder that the country and its leaders have no space, no regard, no love for queer lives. But queer people have always existed and still exist in Nigeria—this is the message of Chukwuebuka’s novel.

Blessings is a memorable, even if tragic, account of a gay Nigerian’s life of oppression within and outside his home as he navigates his sexuality in a homophobic society. Chukwuebuka’s preparation for the vocation of the novelist is impressive, given his rich publications in McSweeneys, The New England Review of Books and Lolwe, and the recognitions his writing has received. He was a runner-up for the 2021 J.F Powers Prize for Fiction, a finalist for the Gerald Kraak Award and Morland Foundation Scholarship, and was profiled as one of the “Most Promising New Voices of Nigerian Fiction” in Electric Literature. Chukwuebuka’s experience of studying creative writing under Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Dave Eggers, and Tash Aw prepared him for the demands of literary activism.

The first time Chukwuebuka and I talked about Blessings was in 2020. It was a brief chat in which he described the then novel-in-progress as “hard” to write. We did not have enough time to follow through the conversation because we were busy researching an aspect of precolonial Igbo culture. That was before the pandemic came and disrupted the world. It took another year to receive an update on the novel, this time from my friend Franklin Okoro, who is also Chukwuebuka’s close friend. Chukwuebuka thanked Franklin in his acknowledgements as one the people “who quietly rooted for [him] from the sides,” but Franklin was nothing less than loud in his faith in Chukwuebuka and his support for Blessings. So, on a Sunday night in 2021, at a bar close to Imo State University Junction, Franklin told me that Chukwuebuka spent the entire months of the COVID-induced lockdown at his hostel in Bayelsa writing the novel. His voice was warm and his manner proud when he described the miracles he hoped the novel would bring to the world. I am not sure Franklin knew the title of the book then, or if Chukwuebuka had even settled for a title at the time, but what emerged from those many months of silent labour is a book that weaves the vulnerability and the daring of the human spirit into an equal, unmeasured, luminance. Franklin was right in thinking of the novel as a bringer of miracles, only that Blessings brings a miracle Nigeria does not yet want to accept, the miracle of the existence of queer lives. It is too late for Nigeria to resist this miracle because Blessings is already out in the world, naming the previously unnamable violence, sorrow, sadness, and shame that characterize queer intimacies in the country. But much more enduring is the novel’s triumph in capturing queer lives as they are, human, utterly human.

Blessings is a liturgy of bodies: the queer body, the maternal body, the diseased body. I am fascinated by Blessings’ display of queer and maternal bodies and broken by the diseased body in the novel. Obiefuna’s imagination of his mother’s cancer is disenabling: “He imagined the cancer eating her from the inside out, he imagined her body failing her. It was the worst form of betrayal.” This reminds me of my attempt to describe my mother’s fight with diabetics, in a personal essay:

“Diabetics ate my mother’s body till it could not find any flesh to feed on.” And my grief, on her passing, was like Obiefuna’s: infinite, inconsolable, closed. The gift of health is so ordinary that we often forget the tragedy of sickness, but the trauma of loss is ever present to remind us of that lost health. But in Blessings, and which is that miracle we speak of, disease binds mother and son in ways that even health did not, could not, aspire to. When I had the chance to ask Chukwuebuka how he created Uzoamaka, his response moved me, and has stayed with me since then:

I dedicated the novel to my dear Aunt Uloma whom I lost to cancer. It’s been so many years, but the ache is still as fresh as ever. I remember looking at her while she suffered, aware of her decline but powerless to stop it. People tell you the peace comes after the loss but that has not been my own experience at all.

Me too. And I do not know if peace ever comes after such a violent loss.

Violence touches everyone and everything it sees. Sometimes it blurs the distinction between the innocent and the guilty, the ugly and the beautiful, the victim and the oppressor. We sometimes find that we are on both sides of the experience, that we are the dilemma we struggle to resolve. Chukwuebuka’s attention to the complicated truth of human nature shows in the variety and unpredictability of his characters, who are as obviously imperfect as they are desirous of perfection. There’s Senior Papilo, who on punishing Obiefuna for something trivial, “studied his face in the light, running his finger gently over the welt on one side of his face” and screamed “Jesus, I can be a beast sometimes.” And there’s Obiefuna who, on hearing the news of Tunde’s abduction, remembered his role, his silence, when his friends beat Festus, their effeminate classmate, for being loudly and proudly queer. It can be shocking, the moment we come to a revelation of our own inner beast. The reach of homophobia is staggering. It targets everything and everyone. That Obiefuna can be found in the camp of the oppressor, the homophobe, says something about the necessity of queer healing and the urgency of queer survival. Chukwuebuka is committed to ensuring that queer narratives, if not queer lives, are heard. We should listen to him.

***

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Chukwuebuka, thank you for gifting me a copy of Blessings.

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

You’re welcome, Darlington.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

The first time we talked about the novel was in 2020 when I accompanied you to the Imo State Arts and Culture. Do you remember?

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

How could I possibly forget? Good memories, aren’t they?

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Of course, they are. And, on our way out of the facility, you said, “I am writing something that might be a novel, and this one is hard.” Reading Blessings four years later, the same day the Ghanian parliament passed the “Human Sexual Rights and Family Values Act” that targets and criminalizes same sex relationships in Ghana made me realize the weight of what you hinted that day. Times have changed since we made that research trip, but everything remains the same. I am concerned about how Obiefuna would respond to the news from Ghana.

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

You could say, in that sense, that the novel’s themes are timeless, which is usually a good thing about any work of art but particularly sad in this regard. One of the novel’s assertions is the predictable callous mis-priority of Nigerian – and by extension, many African – politicians. You hope to be proven wrong when you make these assertions, and then Ghana goes right ahead to pass these obnoxious laws and it feels like a gross vindication. I know Obiefuna is somewhere shaking his head. It sometimes feels very much like all there is to do.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

It’s perhaps more heartbreaking that Ekene, Obiefuna’s brother, now lives in Ghana. I don’t know if Ekene knew about Obiefuna’s sexuality, or if he cared. And, if he did know and care, would he ever raise the subject of Ghana? I may never know. But what I know, for sure, and remember fondly, is that experience in which the brothers came close to manifesting love. It’s a quintessential moment of absolute brotherhood, an enduring testament to the inebriated, unshrinkable joy of being seen and appreciated. I am talking about the scene in which Ekene begs Obiefuna to dance for him. He makes this request ignorant of the fact that Obiefuna had been harassed and beaten in the past by their father Anozie, for dancing, as he puts it, like a girl. How gracefully, how tenderly, how clearly liberating and yet irrevocably melancholic you describe this moment:

Obiefuna grabbed Ekene’s hands and set his feet down to halt Ekene’s swaying movement. He shook himself free. He felt woozy, light-headed. His eyes had begun to spin. “We’re too old for this foolishness, Ekene,” he said. He could not help smiling. “There’s no one watching,” Ekene promised.

Here’s Obiefuna at the downhill of suffering and shame, with an eternal dread of being watched, so conscious of the heterosexual gaze that he now self-polices himself. The impact of homophobia on the queer psyche is damaging. But isn’t it more frightening that family and friends can be and indeed are complicit in this ungovernable, sometimes invisible, act of homophobic violence?

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

Darlington, your reading of this novel is so spectacular you make me almost impressed by my own work, and curious to reread. The scene you just referenced was one of my favorites in the novel and I can picture, even now, exactly where I was when I wrote the very first draft of it. To your question, “frightening” is indeed the word. But also mixed with a sense of helplessness on both ends. One of the things I hoped to address in this novel, I think, is just what you said – the tacit complicity of loved ones in the struggle of queer coming-of-age. I think there’s a very vulnerable spot in the middle – a cross between otherwise unconditional familial affection and devotion, and resistance to what feels immoral to them, and the approach to that can sometimes be malicious. And both, I would say, are equally damaging to varying degrees. To the question of Ekene’s complicity, I like to think that Ekene might not have known initially, being very young and all, but he certainly figured everything out at some point, and what follows is that very human trait of silently sidestepping uncomfortable discourse, hoping it’ll somehow go away if it’s not addressed. It’s also homophobic, if you ask me, but perhaps not necessarily violent, like Anozie’s.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

It’s hard to forget the moment Obiefuna and Anozie finally had a conversation about Obiefuna’s sexuality and Anozie’s brutal response to it, from physical banishment to a boarding seminary school to emotional estrangement. When Obiefuna responds to his father’s admonishment that Nigeria’s antigay law might ruin him, with the following words, “I’ve been imprisoned all my life, Daddy,” I felt obligated to reach out and hug him. I suppose this is why Obiefuna felt alone in the world when his mother Uzoamaka—the only person who truly saw him and accepted him along before he could see and accept himself—died. It is astonishing, even miraculous, the maternal sensitivity that holds mother and child in Blessings. Are they not the blessings the novel proclaims?

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

I couldn’t agree more! That was also another favorite scene, but also one of the most depressing to write. And “imprisoned” felt very fitting a description for growing up queer in Nigeria, I think. It’s sometimes amusing, in a crude way, to think of the government patting itself on the back for doing something damaging, when the real damage, I think, really begins far earlier. In this novel, from when Obiefuna is beaten at eight just for being a good dancer, so much that he quits doing that. When he is bullied in school and abused by seniors, forced to be everything and anything but himself. Can you think of a tougher prison? I have had a couple of readers struggle to reconcile the narrative with the title, which is fair, considering the multitude of sadness within the novel. But you seem to have gotten the idea. Well done!

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

I was sad for Uzoamaka, just as much as I cared about Obiefuna. It is cruel, even dehumanizing, that Anozie did not tell her his reason for sending Obiefuna away to boarding school. The silence around his decision stems from his perception of Obiefuna’s sexuality as an unspeakable evil, something that can and should be erased by silence. And that silence travels. It follows and shrouds queer intimacies. Imagine the finality of Aboy’s tone when he thought about Anozie’s reaction to his sexual connection with Obiefuna. Aboy told Uzoamaka: “He would never forgive me.” In that instant, there seems to be a heartbreaking hesitation to the narrative and the lives that it captures. Silence is a manipulating, disempowering tool. For, in refusing to speak about Obiefuna and Aboy, Anozie denied Uzoamaka the right to know about and participate in the decision regarding her son’s education. Also, he denies Obiefuna the right to autonomous selfhood. Does it bother you, this heteronormative and patriarchal investment in silence as a tool of discipline and punishment?

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

Certainly does. And I like to be clear by the way that I don’t regard Uzoamaka as a perfect blameless victim in this. For as much as she cares for her son, there’s still the part of her who’s resistant to what he is – or, at the very least, taking her time to process and come to terms with it. It’s non-malicious, we can see, so it’s easy to cut her some slack, especially when her behavior is contrasted with the brasher, meaner Anozie. I think too, in addition to all that you say about the use of silence in this novel and in this society, silence is used in this novel as a tool of self-denial. I don’t think Anozie necessarily intended to hurt Uzoamaka by not telling her. It was a way of not being able to admit it to himself. There’s a sense, I think, that something becomes real when it’s named, and addressed and discussed, and most of the novel has involved the parents skirting around the issue without naming it. If anything, I think Anozie was hoping to spare her the heartache of finding out, which maybe goes back to that idea very much in line with patriarchy, of women being emotionally weaker and less capable of handling hard truths.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Beyond the silence in Obiefuna’s house, there are elaborate moments of silence in the novel, especially in the boarding school, where boys who love boys are shamed and beaten into eternal fear and muteness. There are moments, too, when Obiefuna dreams of and wishes for silence. The consequence of Obiefuna’s intimate night with Sparrow remains intrusively, obstinately indelible in my mind:

Sparrow had become a poster boy for all that was immoral and outlawed. He was stalwart in the face of his humiliation, readily admitting to the crime, accepting the revelation that his case was spiritual, that he was possessed by a thousand demons and would need deliverance.

But he did not out Obiefuna, and Obiefuna was grateful for and ashamed of his protection. That school is a space where teenagers are psychologically damaged. It is fearful how institutions of learning that should advance human civilization willing and brazenly commit themselves to the service of homophobia. What do you feel for the boys of Rehoboth Seminary School?

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

It’s interesting you bring that up because that was a classic example of using silence in a different context in this novel. I think the idea in this case really is an ode to the principle of “snitches get stitches” which is very much a boarding school code. It’s also why junior students never report their assaults and every form of abuse in this school flies under the radar. It’s expected, as a young man in this environment, that you were supposed to offer yourself as a scapegoat in any situation you found yourself, as some sort of honorable act of service. It’s not always a good thing, obviously, but wouldn’t you say it was a relief to see Sparrow stick to this code in this instance? And yes, of course, the irony is that homophobia – and other forms of bigotry – often begin from social circles where technically a child should feel most protected. And what better place to experience it in its purest form than a school owned by a religious body?

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

I am turning to Aboy now because he is the beginning of Obiefuna’s love life, and I like how you capture the centrality of that beginning: “It was difficult for Obiefuna to imagine what his life, what their lives, had been prior to Aboy’s arrival.” But Aboy left and chose a woman. Miebi came later, with all the charm and loveliness and warmth that Obiefuna had only associated with his mother. But he left, too, for a woman. Pressured by his family. How do you mend a heart that has been broken twice? Patricia offers an honest, even if somber and disempowering, response to the queer condition in a heteronormative world: “None of us are the same any more.” How do you heal after a fall with the knowledge that you will fall again and again?

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

Let me know when you find the answer, Darlington. It’s the greatest tragedy of life, isn’t it? I didn’t exactly think, however, that Aboy was necessarily queer. The goal was more like a homoerotic attraction rather than an actual queer relationship, at least on Aboy’s part. In that sense, I wouldn’t say he “left Obiefuna for a woman,” although, of course, what’s important is not what we know to be true but how Obiefuna perceives it, and at this point he’s maybe too young and too close to the situation to get an objective overview – and can you even ever be objective when it concerns your heart? Miebi, however, was the real devastation for me as the writer, and for Obiefuna, obviously. It’s even sadder that it’s not a classic falling-out-of-love breakup, rather a survival tactic. Knowing this, of course, makes it no easier for Obiefuna – or for anyone, really.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

I like the name Obiefuna. I had a distant relative who answered to it. An only child, his parents named him as a prayer and a hope for their lineage not to disappear, because of the many years they lived without a child. That is similar to Uzoamaka’s reason for naming her first child Obiefuna. Even the name of Obiefuna’s dormitory “Ogbunike House” connotes the death of childhood innocence that happens there. A name can say so much, can carry deep history, can’t it?

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

Absolutely. I also really like the name. I had a friend who went by it and while everyone shortened it to Obi, I would hail him with the full syllable just for the fun of it. But this novel is also very much about the concept of naming, and the work they do, and I happen to come from a family that is obsessed with names and their implications. I wanted very much to engage with that.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Let me end on a light note. Much of my childhood was spent quarreling with my eldest sister who disapproved of my habit of “rub and shine” bath during cold days. Imagine my delight when I realized that Obiefuna and his schoolmates also do rub and shine. Thank you for capturing it so well:

The thought of ‘rub and shine’ – in which hand-and- leg washing, with cream and cologne application, was substituted for a proper bath – had always disgusted Obiefuna. But standing there at the tap with the cold snaking itself around his shoulders, Obiefuna seriously considered the prospect, if only for this one time.

This consoles me. It feels good to know that I was not alone then. Now, Chukwuebuka, tell me, do you, like me, like Obiefuna, have a history of rub and shine?

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

Oh God, no. That was also very much a boarding school thing for some people, but I never did that! And I’m judging you, Darlington!

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Thou shall not judge, Chukwuebuka. Isn’t that what we’ve been saying all day?

Chukwuebuka Ibeh

Not today, Darlington.

***

***

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions