Ofeimun wrote about the forms power could take, and how the abuse of it had manifested in Nigeria, spilling into the watching of creative output, and most importantly, the censoring of journalistic freedom. He wrote of the critical rhetorics of the British writer, Adewale Maja-Pearce; the Nobel laureate, Soyinka, and of the cruel, politically-maneuvered assassination of the cerebral and fearless journalist, Dele Giwa. I might be able to acknowledge reading Ofeimun’s collection as the reason for the burgeoning need that came in those days to write my own book, a novel. Writing a novel in itself, is pure power, and the ability to create worlds from nothing is man’s chosen way of stepping right up the corridors of God-hood. I wanted this form of power, one so indirect in its punch, and yet so subversive. I had been published in a few journals across the world, but it was different. I needed to step into the cloak of God himself. I was thus experiencing a problem unique to all writers like myself. Creating was a duty, and I was only being punished for being, however inadvertent, a Jonah.

It was June, 2020. I was supposed to say goodbye to Akwa Ibom, but I refused to leave for Lagos. Lagos held little for me. It had become a past I did not want to return to. My first true love added concrete to my resolution. Word had gone that Top Faith, the biggest secondary school in the whole of the state, was looking for an English teacher. I would have paid a leg to work there, if only for a year to stay longer with K. The school paid a good salary, offered boarding with constant power (a rarity in Etim Ekpo), and good, clean water. And even if it offered me only a chance to teach and be paid for it, I was willing to stay in the village with my partner, to last longer with this home I had found. I submitted my documents and waited for a call from the school. Our rent had expired, and K had renewed for six extra months. My father and mother would call asking me to return home.

There are jobs in Lagos. There is nothing for you in that village. They were wrong. My soul was here. I was gambling with power by staying. And if I lost here, I could not, by God, pray to win anywhere else.

There are bank jobs for you here. You speak good English. I rolled my eyes. Twice.

I would return to Lagos in August 2020. Still, a man who leaves home for too long and returns only finds himself leaving each day, until the trails that lead home begin to darken. What is are now traces of what was.

I returned again to Etim Ekpo after over a year, to reclaim my soul and feed nostalgia. I would return a different man to mourn memories that would never be the same, to sit in empty classrooms, listen to music, and introspect. But the classes would be devastated and locked from inside, and so I would rest by a tree and reclaim the times. There would be no fruity cigarettes or milked popcorn. There would be no lodge to retire to even if I waited for the sandflies to come. There would only be a chance to return to my cheap but clean hotel room a few miles away in Ikot Abang.

But it was only August 2020. A lot would not have happened. I would still be with K, be yet to enter those bouts of crippling depression, those contractions from the novel inside me begging to be born, one that would bloom to the surface soon. I had not yet achieved the blatant ennui that came from watching on television in October, policemen shooting unarmed men in their backs as they ran to safety. The skits and pandemic-centered memes spread on Twitter and Facebook saved the sanity of many. Laughter was the only way to numb our raw anguish. Nigerians have long become inured to pain, and in October, they embodied it, claimed it, morphed it into something else, dishing it out, quite unsurprisingly, through both polar instruments of comedy, and the most morbid forms of violence. It was August, and by then I had not cried my heart out, disowning myself from the country of my birth. It was August, and the seed of the impending historical national stampede was still in the hearts of the people, struggling perhaps, to shoot its head above the earth in the victory of birth. I was yet Jonah, begging to be released from the belly of the whale.

***

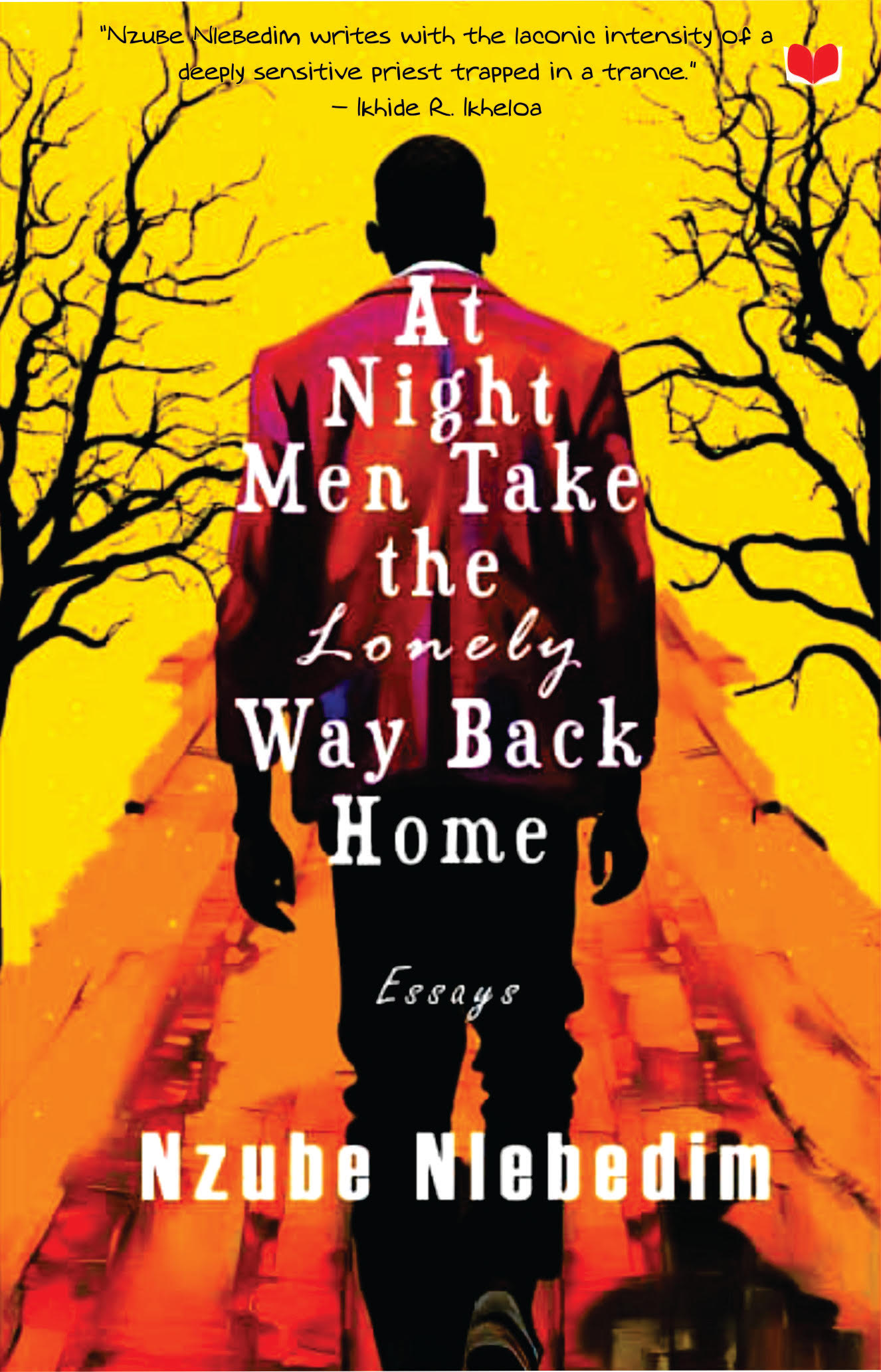

Buy At Night Men Take the Lonely Way Back Home here: Roving Heights (Niger) | Nuria (Kenya)

Excerpt from AT NIGHT MEN TAKE THE LONELY WAY BACK HOME published by Abibiman Publishing. Copyright © 2024 by Nzube Nlebedim.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions