TW: sexual assault

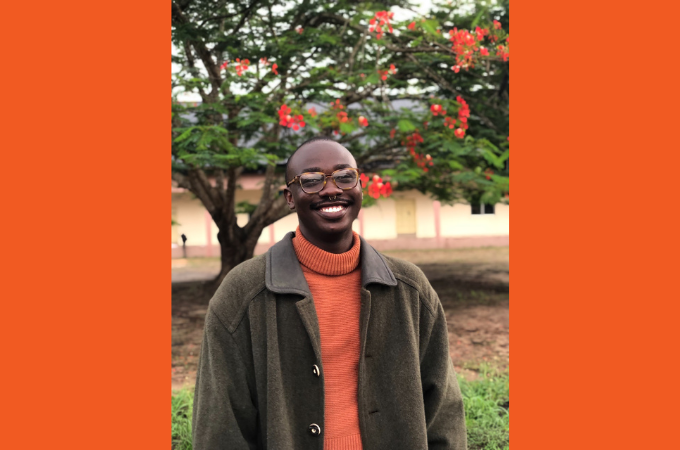

I used to think that I would take up more time than estimated any day I would be called upon to make a brief remark on Edwardson Ukata’s life and work until an occasion presented itself earlier in April. I just told the room that Ukata was so mysteriously energetic, so boyishly playful and yet so incredibly wise. If I have another opportunity to talk about Ukata, I will tell the audience that they have chosen life and poetry above all things. We should celebrate that choice.

A queer nonbinary writer from Nigeria, Ukata was a finalist for the 2022 Anzaldua Poetry Prize and second-place winner of the 2021 SprinNG Poetry Prize. Their work has been honourably mentioned in the Starlit Awards and the Dan Veach Poetry Prize in 2021, as well as the Bergen International Writing Competition in 2023. They are a prospective MFA student at Washington University in St. Louis, and have poems featured in POETRY, Channel, Lolwe, FOLIO, Consequence, Vastarien, DREICH, Afritondo, and elsewhere. Their poetry focuses primarily on familial relationships, queer identity, religion and disease.

Ukata strikes me as someone who has more than one life in this little body of theirs. I say this as someone who has known them for some years. The first time we met in Owerri, they gave me a book, an important book, and also hid a letter, a priceless piece of themself, on my shelf. It took me almost a week to discover the letter. The writing was both the cartography of a lived life and the imagination of a life hoped for. I am glad that Ukata’s life, that past and future, can now be witnessed and envisioned in the present.

Darlington Chibueze

Hi, Edwardson. Kedu?

Edwardson Ukata

Adi m mma, Darlington. Are you fine, as well?

Darlington Chibueze

Of course. Thank you for asking.

A few days ago, I read your poems “With My Father like Scent with a Flower” and “The Triumphant Bellow of the Room.” I want to say that I enjoyed them. But what did I even feel? I am not sure. The poems spoke to me in a way only a tender and honest memoir can. The language is startlingly brittle, even though the poems convey a longing so intimately aching they can break a heart. I like to think of them as semi-autobiographical writings. What inspired these poems?

Edwardson Ukata

Thank you for this insightful reading of my work, Darlington. Analyses like this, into what I write and why I write them, make me very happy, because they show that somehow, somewhere, someone heard my writing talking, and paid attention to it.

While writing “With My Father,” I was looking deep into myself to discover the things that changed so much within me, enough to have made me as strong as I was that day. It was a few months after I had tested positive for HIV, a few days after I had got used to the nausea that was a side effect of my ARVs. I was reflecting on my life, on how far I had come, and imagining my end, how quickly I had reached the edge of my life. My father had called for maybe the tenth time in barely four days because I had told him I was sick about a week before and because he was scared, I think, of losing his first child. During the call, I told him I was better, but I was not. I was busy asking myself how I got there.

Darlington Chibueze

Did you find any comforting answer?

Edwardson Ukata

It was not a question I did not know how to answer. I had sex that I wanted for the first time when I was fifteen. I gave myself to a man who told me his first son and I were agemates, and it was not because I loved him or because I wanted so badly to taste the liberty of intimacy. I wanted to spite my father and God, especially. It was an act of revenge, a foolish one, perhaps. But necessary, at least for me.

Darlington Chibueze

I am so sorry you went through all of this alone, Edwardson.

Edwardson Ukata

I needed the sex, Darlington. I needed it to be strong for myself, because months before becoming fifteen, I was bullied for being effeminate by students and teachers in my secondary school. The biology teacher once said to my face that if I dared to defend myself against the accusations that I was gay, she would strip me naked and check my anus for any signs of penetration.

Darlington Chibueze

This is the dead end of humanity. You were just a boy. Only fourteen.

Edwardson Ukata

I was scared. Really frightened. I had let my cousin touch me many times without saying anything to anyone. So, I did not defend myself but hoped that God would do something to take it all away. I was devoted to Scripture Union. I was being groomed to become the school’s chapel prefect, so I believed that being homosexual was against God. But I knew in my soul that I was homosexual. That was why I did not defend myself. There’s no need hiding the truth any longer. God took nothing away from my situation. They let it all play out, and maybe because they truly knew the truth would make me free. Somehow. Even after many sessions of fasting and praying to God to change me, I was serially sexually abused by a senior student for two weeks, with a crowning day of forceful and dry penetrations by the senior and two others who thought it would be fun to join in some party of boyful flesh.

Darlington Chibueze

Where were your parents then? I am sorry to ask.

Edwardson Ukata

My father held me responsible for everything that happened to me. It was because of this experience, and my father’s reception of it and me, that I decided to take my revenge. I remember my father saying nothing from his loins could let themselves be used the way I had. I vowed to have as much homosexual sex as possible so I would piss God off. And it is rather funny that two years after I broke myself out of that vow, I came down with the disease from someone I loved and respected, and not some random man off a dating app. I am paraphrasing, but my father meant I was not man enough, or simply son enough for him, and for many days afterward, shame tempted me to kill myself. “With My Father” is a reflection on this experience. I realized that to find my voice, I needed to die first and be reborn.

Darlington Chibueze

What about your mother?

Edwardson Ukata

My mother is part of my resurrection. In “With My Father” and “The Triumphant,” I use the imagery of my mother as a metaphor for the death of my old self and the birth of this new one. In both poems, my mother is a memory. In both poems, my parents and I are all just people in a world of trauma, pain and joy. In both poems, there is ordinariness. There are algae, insects, and the familiar sound of daily death. The poem my father reads aloud in “With My Father” is a piece I wrote, and which he has read aloud in real life. It is titled “Homeboy,” and published in Folio. I remember the pride in his eyes after reading the poem; the way he clapped and smiled. But I have not forgotten that he asked me what I meant by saying I was a “queer writer” in my author bio, and I answered with absolute silence.

In “With My Father,” I also remember a youth corps member who saw me when I was fourteen, after the abuses, and helped me love something other than pain, well until I wrote my senior secondary certification examinations and left the school into the streets, with the “extravagance of a lamp on the side.” There is also the memory of a friend’s argument with his father about his sexuality on the day of his mother’s funeral, and the memory of my aunt, who is my third mother, dying so young and appearing in my dreams with enough candy to fill a room.

Darlington Chibueze

I hope that someone will come across these poems and, even if they do not know the stories they tell, feel the experiences they embody, and let their beauty and truth make them free.

Edwardson Ukata

I hope so, too, because there is a need for solidarity among queer persons and people living with HIV in Nigeria. In their own ways, these poems are a work of solidarity. In “With My Father,” I expressed the delirium of having HIV by showing that I wandered through the compulsions of life and death. This line in the poem, “the end of all living things is the beginning of living,” was a consolation to myself, that even though my life may now be cut short, I would live somehow through someone who knew me. And this also speaks to the reality of queer lives in Nigeria.

Darlington Chibueze

It is a life at the mercy of death. A life in need of nothing but itself. The experiences of queer people in Nigeria can break anybody who still has a heart. When I read your poem “Verbiage,” I saw Nigeria losing its soul.

Edwardson Ukata

Thank you, Darlington. I am glad you read the poem. Queer people do not need families that disown them for who they are. We do not need cultures and societies that tell us to shut up about abuse. That is why I wrote “Verbiage.” Our imaginations of Nigeria, and the place of the queer population in it, evoke a sense of emotional emergency. I write to tell and to remind the world of the horrendous experiences of queer people across Africa; to show that our families are not doing enough to protect and care for us, but that they need to; to show that our hallowed cultures and traditions are killers, tight corners; to show that my country is an organic grave. The image of the father in my poems is also a metaphor for Nigeria. And so, as in “Verbiage,” Nigeria terrifies me.

Darlington Chibueze

The world deserves to know the truth about how Nigeria treats its sexual minority. A nation at war with its own citizens. I am glad, Edwardson, that your poetry and life contribute to that global truth-telling.

Edwardson Ukata

So am I, Darlington.

Darlington Chibueze

“With My Father like Scent with a Flower” and “The Triumphant Bellow of the Room” were published in Poetry and Vastarien, respectively. What informed your choice of submitting to these magazines, as against literary journals based in Africa?

Edwardson Ukata

Poetry magazine is probably the most definitive outlet for any poet’s career. By submitting to them, I was seeking validation and, importantly, the weight of mass media in the promotion of my work. I wanted to know if my life and the lives of people like me were important enough to the major media. Major journals receive more funding from institutions that support arts and literature. They have a much wider reach.

Darlington Chibueze

But there is also the concern about writerly desperation. What will a Nigerian writer do and how far can they go just to be published in an American magazine?

Edwardson Ukata

In recent times, alleged critics have accused Nigerian poetry of Americanization based on the assumption that Nigerian poets are now more concerned about the pay, the fame, and the feel-good-ness of being published in American magazines. To be honest, being published in a major American magazine feels absolutely good. The average Nigerian, the average African too, believes that Western institutions are superior to ours. It is important to keep in mind that in the way the global system works, they actually are, because they are better capitalists. The more capacity to exploit a person has, the more they do, and by such, the more power they amass. And whether or not it is true power, whether or not it is kind power, power is power. And, in the end, the higher power wins.

Darlington Chibueze

In a manner of speaking, you are suggesting that the critics are right.

Edwardson Ukata

They are not entirely wrong, but their arguments are misdirected. The Nigeria and Africa we now know are products of European colonialism and westernization. In recent times, every part of the world has encountered America in as many ways as possible, because the country exerts itself as a world power. We have even abandoned the British English given to us Nigerians, and now speak the American version. That is because we consume America in all its beautiful and tragic appearances. We like Hollywood movies and adore Beyoncé. It is only natural that something ever-present in our daily routine is evident in our lives, from the way we dress to the way we make art. However, I do not agree with the critics that a Nigerian’s story is not Nigerian enough because it is published in an American magazine. I do not believe that it loses its “Nigerianness.” I think it gains more of it, because what expresses ownership better than the boldness to display that which we own to the world?

The English language is not originally ours. But now, there is a Nigerian English accepted by the original owners of the language. If we can take a people’s language and make ours out of it, what then is poetry that we cannot take? We take philosophies and personalize them. We take product designs and personalize them. It is the nature of the world to be independent and still depend on something or someone, to be incredibly personal and still impeccably public. A poem by a Nigerian is Nigerian even if it is written in Sumerian language and published as a discovered text from ancient Macedonia. On this note, I appreciate the many African magazines that champion African voices and publish quality work. Magazines like Lolwe, Brittle Paper, Isele, The Shallow Tales Review, and The Muse Journal need financial support to be able to publish more writers and give visibility to the African story.

As for submitting to Vastarien, I did not know of any African magazine that published horror writing, even though they may exist. I was just lucky to have seen the call for submission and remembered I had a horror poem somewhere in my catalogue.

Darlington Chibueze

What kind of relationship did you have with the editors of these magazines? In your experience, is the alleged reputation of American editors for erasing the “Africanness” of African poetry or the “Nigerianness” of Nigerian writing something real, something we should all be worried about?

Edwardson Ukata

I have never experienced that. I think all editors want quality work, although there are also concerns about marketability and readership. During the editorial process of “With My Father,” there was only the issue of alignment of language. I had written in British English, and to fit into some grammatical boundaries of American English, the hyphen I had put in “nonexistence” had to be removed. In “The Triumphant,” a few semicolons were replaced with periods. For “Verbiage” there was a continuous issuance of galleys to ensure there were no errors in the final product. In all, the editors were kind and gentle. Angela Flores of Poetry was exceptionally kind. Katherine De Chant of IHRAM, too. Holly Amos kindly suggested I rephrase a part of my response for the Exophony collection for Harriet Books because she did not understand what it meant. It’s a popular Nigerian phrase, “talk more of” or “talk less of.” It is used to suggest that if something of lesser importance can have so much deliberation on it, how much more is something of higher importance? Jon Padgett of Vastarien was so warm and professional in our email correspondence. I look forward to working with these editors again.

Darlington Chibueze

Perhaps I forgot something earlier. Congratulations on your admission to Washington University’s MFA programme in creative writing.

Edwardson Ukata

Thank you so much, Darlington.

Darlington Chibueze

What informed your choice of the US?

Edwardson Ukata

The choice to pursue graduate studies in the US, particularly an MFA, has been a deeply personal and carefully considered decision. My journey is shaped by my experience as a queer, nonbinary individual living with HIV in Nigeria. I imagine that the US will provide the safety and sanity I need for my work. Bearing witness to the harsh realities that members of the LGBTQ+ community face in Nigeria has profoundly influenced my work. I can never forget witnessing the brutal lynching of a beautiful homosexual boy on a street in Omoku, following the implementation of the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act in 2014.

Darlington Chibueze

If I had witnessed that, I don’t think I would ever want to forget it. I am really sorry, Edwardson.

Edwardson Ukata

The tragedy is that I will keep seeing such things if I remain in Nigeria. The queer condition in Nigeria has made me resolve to use poetry to bring light to darkness. I want to articulate the often-unheard voices of queer Nigerians and advocate a safe identity and social justice. I believe that my experiences provide me with the power to transform chaos into art. My poetry is a form of activism, a choice to illuminate the grief and hope I embody. An MFA programme in the US offers me the perfect platform to expand this mission, allowing me to develop my craft, broaden my perspectives and engage with a diverse and supportive community of artists and scholars. However, it is also important to note that while Nigerian universities offer MA programmes in various fields in the humanities, there are no substantial MFA programmes in creative writing here. Creative writing deserves a place on our curriculum. How can a nation retain its artists if it does not offer them an opportunity to thrive?

Darlington Chibueze

Would you say I ask a lot of questions if I ask: why Washington University?

Edwardson Ukata

Of course, not. I am grateful for your interest in my life and work. Washington University in St. Louis is exceptional both for its commitment to fostering a culture of excellence through diversity and for encouraging freedom of inquiry and expression. The faculty’s dedication to nurturing each student’s unique voice is something I now consider a necessity for my growth as a poet and activist. I am excited to soon work with Mary Jo Bang and Eduardo Corral, amazing poets and human beings. I look forward to bringing my passion for teaching and community-building to the university, by initiating workshops and retreats to inspire and support marginalized communities.

Darlington Chibueze

Edwardson, I wish you all the best moving forward.

Edwardson Ukata

Best wishes, as well, Darlington.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions