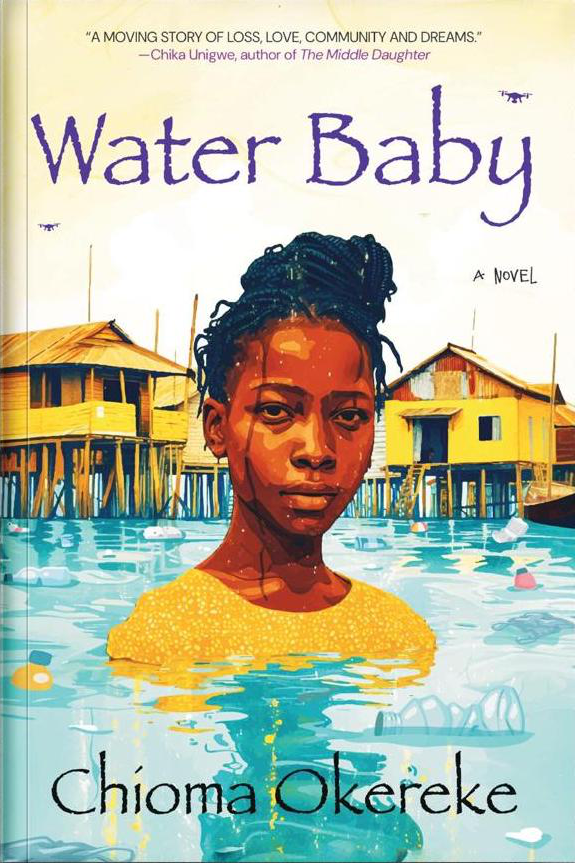

There’s an old tale where we live about throwing a newborn into the lagoon.

If the baby drowns, it is illegitimate and the mother must be banished from the community. But if it floats, the infant is embraced by all. They say fathers used to celebrate their child’s birth with this test. It must have been a trick, though, as every- body knows that all babies float.

I was born in the water. That’s what Papa says but it’s a fiction. I wasn’t born in a hospital or on land; most of us in my community weren’t. We drew our first breaths on Adogbo, though according to Papa, my first moments were almost in the lagoon itself. Makoko is what the outsiders had originally called our settlement hundreds of years ago, due to its abundance of akoko leaves, and the name stuck for the community on the Lagos coast just across from the Third Mainland Bridge. To strangers, it’s a slum, a metallic and wooden eyesore built over a stinking bed of ever-mounting sewage, spreading out across the smoke-filled horizon. For the government, it’s the impediment between even larger coffers for them and prime waterfront real estate. But to us, who are from here, Makoko is simply home.

The Nigerian government likes to pretend that we don’t exist, but we’ve been here for hundreds of years, our wooden houses resting proudly on their stilts above Lagos’s charcoal-coloured lagoon. We’ll remain here for some time, no matter how many attempts they make to push us out.

Mama had plenty of babies in her belly before me, but only a few of us stayed. That’s not only an issue with the women in our family, as she’d explained, but with life here on the lagoon. There’s a high rate of maternal and infant death among those living on the water, which is strange considering that we all originally come from the womb having been surrounded by liquid. Still, many women lose their children – although there’re plenty to go around – as there are very few doctors here to speak of.

So, Mama had some false starts before Dura came and then many other miscarriages before it was my turn nineteen years ago, followed by Charlie

Boy five years later. I was fearless, Papa used to say. It’s why I was able to be born.

Mama had been visiting her best friend when I announced my early arrival, pounding hard on her stomach and pelvic bone. Auntie Uche had protested that it was too late for her to leave. Having had more babies than Mama, Auntie knew I was well on my way into the world, but Mama had been insistent. She’d wanted to return home to have me in her own bed, so they’d stepped gingerly into a canoe for the short ride back. Papa wasn’t even there but claimed Mama’s labour was so painful that he’d heard her while he’d been far out fishing with the other men. Mama’s voice had travelled across the water and spooked the fish, which rushed to their nets, delivering them a glorious bounty!

As I’d inched through her passageways, Mama rocked the canoe so much that they’d almost fallen overboard. Auntie Uche could only look on in fear as she prepared to rescue Mama from the filthy waters, but then something odd happened. A mighty invisible hand had reached out from within the lagoon and pushed her upper body firmly back in place. Mama let out a heavy cry and then slid to the boat’s bottom so that Auntie Uche could row her home before I slipped out through her legs from underneath her wrapper. We’d stayed in the boat tethered together by our cord while my aunt screamed for help and our neighbours went to fetch the other women.

Papa was astounded when he came home later that evening, covered in sweat and scales. His eyes were large and his mouth even wider when he saw what Mama had produced. He said I looked like one of the fishes he drew out from the water daily, in shock from being extracted from their natural habitat, their eyes big with fear as their cheeks contracted from struggling to take in the air out of the water.

He retold this story many times when I was smaller. I used to ask him if I’d been slimy like the catfish that we ate in the past, which the lagoon used to be full of when it was teeming with fish. He’d reply that I was, but that Mama had cleaned me up, so by the time we met, I was dry but naked and as beautiful as a mermaid.

He said I was practically born with one foot in the water and that Mama had been helped that day by the deity Yemoja herself.

It’s why they named me after the water spirit, though every- one calls me by Papa’s pet name: Baby.

***

‘Good morning, where you wan go?’ I ask as the woman waiting for a ride gesticulates wildly for my attention. Her black trousers and blue button-down shirt make me think she’s a bank worker or perhaps has a government job on the mainland. She removes her hand from over her eyebrows, her makeshift protection from the glare of the blazing sun.

‘Carry me to Dr Ofong’s hospital,’ she points off into the distance, dislodging the large handbag from her shoulder.

‘Okay, enter,’ I respond before she steps down into my canoe, followed by two women wearing dresses in the same pink diamond print. Looking around quickly, I inspect my domain through her eyes. Thankfully, despite my hectic sailing in a rush to get here, the seats are dry. The floor of the canoe is empty apart from my ever-present sweat cloth on the seat next to me with my bottle of water.

‘Go quick quick, please! I’m late for an appointment,’ she begs before shooting a bullet of spit into the dark water. Even if I wanted to linger in the hope of another customer, I now can’t for fear of losing her.

From the way she wrinkles her nose, it’s clear that she’s a visitor to the community. As far as the eye can see, there’s dirt from refuse spat out from the lagoon’s lips a million times over or pushed in via shipping lanes and kept here by the currents. We’re used to seeing the waterways filled with refuse; trash jam-packed under every house as decades of garbage bobs on the water’s surface like rising secrets that want to be told. The smell of Makoko is something we are long accustomed to.

‘This place go kill person,’ she mutters under her breath as we glide through a particularly pungent patch of the lagoon.

My oar slides into the water like a hot comb through hair as we push off from land towards Adogbo and I listen to the chatter of my two other customers, one whose laughter reminds me of Dura, most likely hawking fish at her stall on Better Life Market, her latest newborn strapped to her back. This journey across the lagoon is what I enjoy the most. There’s a bustle in the waterways and pockets of peace too, which are harder to come by among the houses.

A bead of sweat slides through my braids, and I shake my head vigorously to generate some breeze, but my executive passenger frowns at me as if I’m in danger of rocking the boat.

‘You’re safe, Auntie,’ I say to reassure her, to soften the ice block I’m ferrying towards the community, but she looks through me before closing her eyes.

On a good day, I’ll make half a dozen more trips like this before I go home to deal with my chores or to carry out one of my other side jobs. A person must have many other lives on Makoko in order to eat and sleep. But bobbing along on the water in the traffic jams created by the other boats or drifting far away with only the lights on the horizon for guidance is where I feel the most free.

Alone on the water, I can hear my own thoughts without the voices of others telling me what to do or who to be.

Many of us set our sights on the mainland, the furthest we can stretch our imaginations before they break. Parents dream of us leaving Makoko and doing better than they did for them- selves, and eventually we dream it too, all the while knowing it to be an elusive fantasy. Not many of us have done it, yet that hope pulses within us like a beacon.

I gaze longingly beyond the mainland to the skies and in those moments that are solely mine, I’m free to fantasise about the future.

One that I’m actually wanting.

***

Buy Water Baby here: Amazon

Excerpt from WATER BABY published by Masobe Books. Copyright © 2024 by Chioma Okereke.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions