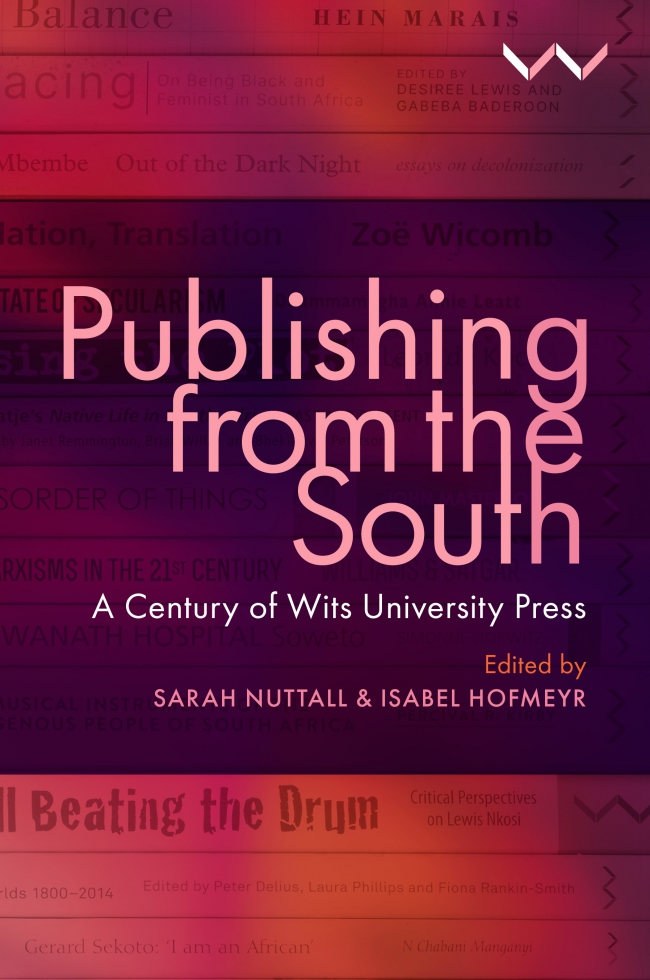

INTRODUCTION: Experiments in Writing the History of a University Press by Sarah Nuttall and Isabel Hofmeyr

In recent years, intellectual production and cultural theory have focused on the concept of ‘theory from the South’. While generating analytical models that are rooted in the South, this conceptual approach has limitations as it frequently, though not always, continues to mirror the South from the North. Another angle has been ‘writing from the South’, a genealogy long investigated by postcolonial literary studies. A third move has been to think with the idea of the ‘global South’, which has become a widespread way of investigating socio-political developments in what used to be termed the ‘third world’. This book offers a fourth term and a challenge – namely, ‘publishing from the South’. While drawing on these larger debates, this concept engages with the material realities of Southern-based publishers. Although these publishers cover a gamut of institutional forms (scholarly presses, small trade publishers, religious publishers, jobbing presses, educational publishers), our focus is on scholarly presses and the Southern publics (be these buyers, readers, reviewers, students or interested bystanders) they sustain. None of their work precludes worldliness and a reaching for international audiences, but it shifts the terms of reference by publishing in the South first. Their strategies work to authenticate Southern intellectual publics and to support scholarly impetus from within the universities in which they are located.

In 2022 Wits University Press, formerly the Witwatersrand University Press, at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, marked its centenary, making it the longest-standing, most established university press in sub-Saharan Africa. From the day that the University opened its doors in 1922, it had a publishing wing. For an institution that started as a mining school, this choice may, at first glance, seem unexpected. Yet, the Press was set up to publish research undertaken in the University, and much of this had been shaped, directly and indirectly, by prerogatives from the mining industry and its desire to control its African workers. A major focus was to constitute Africans as objects of linguistic, anthropological and medical knowledge. These fields of study were identified as an opportunity for presumptively white scholars to ‘contribute to the world’s knowledge of anthropological and allied subjects’, rather than leaving these fields to institutions in Britain and Europe (which nonetheless remained points of both aspiration and envy, not to mention a model for what a university press should be).

Like the University itself, the Press from its start was embedded in the contradictions of Johannesburg, and of the global South more generally. Its aim of producing local knowledge had considerable substance, but it was equally shaped by the racial and gender inequalities of the social order. The Press served a tiny and overwhelmingly white and largely male elite with black writers represented in infinitesimal numbers. This imprimatur of white patriarchal privilege ‘watermarked’ the Press and its publications and only began changing in the late 1980s.

As did most university presses in white settler colonies, Wits Press looked to Oxford for its models. As Elizabeth le Roux demonstrates in her pioneering discussion of university presses in South Africa, representatives from universities in South Africa behaved similarly, travelling to Oxford University Press (OUP) to learn about its operations.2 Yet, this aspiration to resemble OUP was inevitably hubristic and the Press was fashioned out of, and in opposition to, a range of influences. Operating in colonial academic contexts with limited resources, South African university presses were initially modest, home-made affairs, often service departments within the university or an adjunct to the library, lacking full-time staff. Like the external wings of OUP or Cambridge University Press (CUP), which sought to exploit the colonial educational market, Wits Press dabbled in this field, producing lecture notes and field guides for students. Within South Africa, Wits Press took shape in a context of existing traditions of publishing, including Christian mission presses and an active black periodical press. One theme of the Press’ early production and its journal, Bantu Studies (now African Studies), was to differentiate ‘scientific’ anthropology from amateur mission ethnography. As regards the black press, Wits Press both drew on its resources and distanced itself from these publications. As Isabel Hofmeyr indicates in chapter 7 in this volume, B.W. Vilakazi’s poetry collection Inkondlo kaZulu comprised poems which had first appeared in the black press, with the Wits Press volume being presented as of more value than the ephemera of a newspaper.

Publishing from the South explores what Wits Press achieved within these constraints while also considering its limitations (and what its modes of reinvention might look like). In widening and deepening our understanding of the Press as a global South scholarly publisher, it asks how this category can contribute to a broader understanding of Southern knowledge production.

Whether in Australia, New Zealand or the United States, the story of these anglophone colonial university presses tends to be told as a tale of gradual professionalisation, a movement from amateur ad hocism to modern editorial, marketing, distribution and staffing practices. While there is much truth in this incremental story, its teleological assumptions cast a condescending and obscuring shadow on the early history of these presses. This volume takes a less teleological approach, situating Wits Press as an institution whose contradictions and fault lines are as interesting as its incremental improvements. In taking this approach, the volume does not necessarily regard the earlier work of the Press as naïve or old-fashioned and its later production as more sophisticated.

The chapters that follow explore emerging and at times unexpected angles on the Press. Cumulatively, they look for surprises as much as for persistent patterns, for revelations in and from the archive as well as through personal publishing biographies. Rather than only or even primarily following the Press chronologically, or via the ‘communication circuit’ beloved of book historians (Author, Publisher, Printer, Bookseller, Reader, etc.), the chapters seek out less traversed pathways. While committed to profiling some of the Press’ most famous authors, such as J. H. Soga, B. W. Vilakazi and Chabani Manganyi, the volume also experiments with something of a novel genre: contemporary authors’ biographies of publishing with Wits Press. While one might anticipate these accounts to be hate mail (‘my publisher did not do x, y and z’), in fact these bio-essays are the reverse, speaking of the pleasures of publishing with Wits Press, especially vis-à-vis the challenges of what Srila Roy in chapter 13 calls the Northern ‘academic publishing industrial complex’. Not least, of course, they also issue challenges of their own to Wits Press.

A focus on the Press provides insight into broader intellectual and disciplinary formations. These include the shaping of African languages, anthropology, archaeology, and feminist and gender studies, which happened on campus, in the Press and beyond in a range of non-university settings. A cluster of articles explore the African Treasury Series (formerly the Bantu Treasury) which played a crucial and contradictory role in shaping African-language literatures. The chapters direct attention to the books themselves, their covers, their biographies and their reception. We also peer behind the scenes to understand how author contracts took shape at the Press. Based in South Africa or publishing in the South, the contributors are Southern-facing scholars or publishing staff whose contributions create a vital and compelling analytical intervention from the vantage point of African intellectual formations on publishing South historically and in the present.

***

Order Publishing from the South: Amazon

Excerpt from PUBLISHING FROM THE SOUTH published by Wits University Press. Copyright © 2024 by Sarah Nuttall and Isabel Hoymeyr.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions