D. O. Fagunwa is one of the first to write an African-language novel or what he likes to call “phantasia novels.” His most popular novel, Forest of a Thousand Demons (1938), was originally written in Yoruba and later translated in English by Wole Soyinka. This week, I’m sharing with you a short essay by Fagunwa published in 1960 in a Nigerian magazine called Teacher’s Monthly. The essay gives a unique take on what it means to write an African novel. It’s a rare piece, so read and share. Have a lovely week!

A novel which involves the mysterious is perhaps the most difficult to write.

—D. O. Fagunwa, 1960

Teachers often ask questions on the writing of a novel. Of late, these questions have increased. How do novelists produce their works? What is the difference between a publisher and a printer? What are phantasia novels?, etc. Here an attempt is made to reply to some of these questions, and the reply represents my own personal opinion.

A novel is a written prose fiction. It has developed from the word “romance” which is applicable to verse as well. Also we sometimes here of “novels in verse.” In other words the writing of a long story in a connected form, which, though it had not happened, is presented as though it, in fact, had happened, may be regarded as a novel.

The aim of a novelist is to present to the public something interesting to read, and the success or failure of a novel lies in how far it can get a hold of its readers and compel them to read on. This is why its place is of special importance in a community such as ours where people as a rule do not read works in their own language except in so far as they have a bearing on the passing of this or that examination.

No, all aspects of life do not interest people equally. Love for instance interest people most. We like to love and be loved. We also like to watch those who are loving or being loved. Money interests all: we need at least some for our existence and so we are interested further in the rich and the poor. Adventure interests some but not all. We hear of people who walk long distances, swim wide expanses of water or climb mountains. The mysterious interests us one way or another. What for instance happens to us after death? Is it true that if we behave well on earth we go to paradise and otherwise to hell? Are there ghosts? Do spirits inhabit trees, rocks, rivers, streams, etc? What a novelist does is to present one or more of these aspects of life and weave a long story around whichever he takes.

All these aspects of life are not equally difficult to write about. A novel based on love is not very difficult to write because even if all the true stories of love we hear are written and joined, they easily look like fiction. Equally a novel based on money is not very difficult to write since stories connected with misappropriation of money are common in real life.

A novel which involves the mysterious is perhaps the most difficult to write. In such a case, the writer goes really into the world of the imagination and therefore it is necessary for him to have had an inborn gift of imagination. In literary history, only few brains have produced this type of writing and the product lived long.

John Bunyan has been described as the father of English novels. His Pilgrims Progress describes no other thing than the journey from this world to the world to come. So is Spenser’s Faerie Queen, a novel in verse.

The term “phantasia novels” is an invention used for describing novels written in African languages in Nigeria but, in literary language, I have never heard of that term. However, I know the type of novels that the majority of Western Nigerians have written, my having been a long time in the Publication Section of this Ministry, and being responsible for reading and assessing Government publications has placed me in a position to know what our people write.

Let me say, in the first place that it is not correct to say that all Nigerian novels have something of phantasy in them but the majority do. I usually term these Spenserian because they so much resemble the works of an English writer, whose works were published in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century A. D., called Edmund Spenser. The fact about them is that if well handled they have a peculiarly forceful way of driving an idea home. They interest Nigerian readers a good deal and I have always encouraged rather discouraged them. Compare this personification in Book I of Spenser’s Faerie Queen. In Spenser’s view, the reformed church was full of misdeeds. He does not as a result describe these acts of omission and commission in mere words, but instead, he personifies Error as a horrible monster, half-serpent half woman, living in a dark, filthy cave, to be fought by a knight who himself was the son of a fairy. Here, when everything of the misdeeds of the Church could have been forgotten, the picture of this monster would remain in the mind.

As has been pointed out above, our duty is to present to our readers what we know will interest them. We should not merely copy others but should give first consideration to the need of our society. Experience has shown that British humor is not the same as the African’s, and while it is doubtful whether the British would like an element of phantasy in a novel, surely some of the continentals will do. Besides, there is nothing wrong in making our own kind of writing our special contribution to the literary history of the world. Nigerian society is broadly divided into two, namely, the educated section and the non-educated, (those who have been to school and those who have never been). A big slice of the former together with nearly all the latter believe in juju, spirits, ghosts, etc., and a novelist should take an account of this.

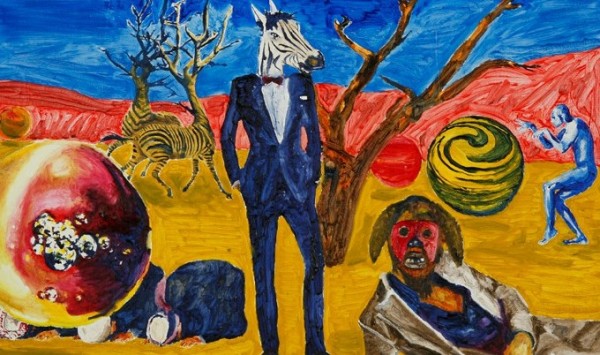

Images via Nigerian artist, Boloebi Charles.

Essay republished in Early Nigerian Literature by Bernth Lindfors.

Literary Things Invented by African Writers | Fagunwa’s Phantasia Novels – Nigerian Eye Newspaper February 28, 2019 14:01

[…] not have appeared anywhere else. Phantasia Novels I came across this term in D. O. Fagunwa’s 1960 essay about how to write a novel. Fagunwa is a Nigerian fantasist who wrote mostly in Yoruba. “The term phantasia novels,” he […]