“The sky in Sabon Gari is blue and high, like all of Kano’s skies. It is beautiful so long as your eyes remain on the heavens. Everything else strives.”

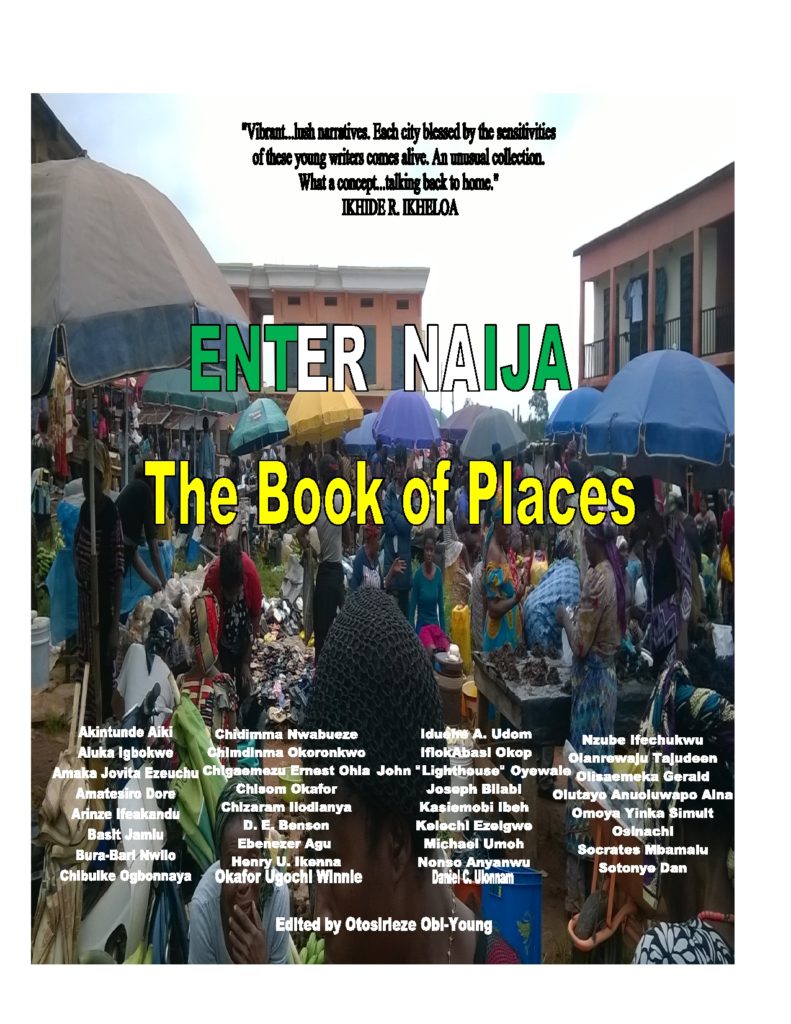

On October 2, we published Enter Naija: The Book of Places, an anthology of writing–non-fiction, poetry, memoir, fiction, commentary–photography and digital art about places in Nigeria created to mark Nigeria’s 56th Independence anniversary. The project, with a delicious Introduction by Ikhide R. Ikheloa, was edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young and features 35 contributors exploring the concept of Place across a host of Nigerian cities. We are republishing a few highlights from the anthology, and here is our first: a non-fiction piece titled “New City,” Arinze Ifeakandu’s lyrically orgasmic recreation of life in Sabon Gari, Kano.

***

New City

By Arinze Ifeakandu

IF KANO WERE my child, I’d name her Blue, after her perfect sky. Morning brings the egrets, their cries filling the dogonyaro tree in front of Oga Ali’s compound, their whites splashed all over the greenness, an indifferent tribute. By afternoon they are gone, to return at twilight when they share the sky with bats. Unlike the bats, the egrets seem to have a singular purpose: to glide to that tree and settle in for the night. The bats, on the other hand, do not seem to be in a hurry: they have all night to be alive.

The humans who share the city with the egrets and the bats do not have all night—they have spent the day building dreams and fighting to stay alive, and like the egrets they must settle in for the night. But they, too, must be alive. It doesn’t matter that the bats have slept all day and can now stay wide awake for the night. Humans are not altogether popular for their respect of biological limitations, which is why sometimes an aeroplane growls through the sky. And so at dusk a group of friends find themselves in Burma Road where their church is located. They begin with a brief prayer, and then spend the rest of the evening trying to sing in key.

Other humans have other ways of burning the night, many other ways, all of which seem to involve being with other humans. It seems odd, really. Having spent the day interacting with others, misunderstanding others, haggling with others, isn’t the temptation to curl into oneself? This instinct to always gravitate towards one another must spring from a certain loneliness.

And so.

Beside the church on Burma Road Street, a woman is singing with synthetic shrillness, her voice piercing over loud speakers. The Hausa words have taken on a Bollywood tinge, and it is easy to imagine this singer, perhaps a petite Hausa lady with a ring in her nose, in a sari. A million motorcycles are parked in front of the motel and a million men are smoking and laughing and moving their hips. It is a bedlam down here, whereas in the sky there is an infinity of stars. The partiers belong there but they do not belong here. Which brings us to our point of contradictions.

THERE IS SABON Gari, and then there is the rest of Kano. The sky in Sabon Gari is blue and high, like all of Kano’s skies. It is beautiful so long as your eyes remain on the heavens. Everything else strives. The houses are built with shrewd pragmatism, bungalows fading gradually, interposed as they are between tall blocks of flats. Many rooms in these flats have not seen sunlight in so many years: when one window opens, it shakes hands with another. On a good Saturday morning a group of teenage boys will convert a minor road into a football field, grouped in sets: four-, five-, six-man teams. On a corner, beyond a gutter choked by grass and sand, littler children will be rolling tyres, playing Ten-Ten or Police-and-Thief.

It is difficult to place Sabon Gari, especially for those who live in it. It lacks the coherence of identity that characterizes towns, and whereas it is large and sprawling, its night lights do not gleam with the tender sublimity of a city’s. It is the dumping ground of the unwanted and the saving grace of the sons of the soil, and in that way it is a place of elegant contradictions.

THE PEOPLE WHO come to the motel beside the church to be alive do not live in Sabon Gari. They have come from Bompai and Yankaba and Kano City, from all the places in Kano that smell of freshly brewed coffee. They wear jeans and outrageously colourful sneakers. One evening, I share a keke with one of the men who have come to be alive. He is handsome and smells nice. We are both coming from Bompai of sweet coffee smells and bright lights, and are now heading the same way, but for directly conflicting reasons: I am an egret, and he a bat.

In Bompai, the keke glides, and when I look outside I see the lights of the city. The houses look primed, like eclectic Afropolitans posing for a picture. There is an intentionality to the streets, an organization. I do not doubt that the houses will be full of sunlight.

France Road, and we are in Sabon Gari. After that, the keke begins to dance through the road. The driver complains—he does not normally come here, he says, but. The hole on the road around Ibadan Road has not yet been filled, and so the driver has to go all the way around the main road. The man beside me says something in Hausa, and when I stare at him he asks, “Are you too going to the party?”

“No, no,” I say, and hope that he can see my smile in the dimness of the keke. I want to keep talking to him. Did he know, I want to say, how ironic it is that my friends and I had gone to Bompai to have a nice quiet time in a nice quiet place whereas he was coming to Sabon Gari to have a bombastic time in a place that never shuts up?

- A certain governor of Kano State asked Igbo businessmen to fix the road around Emir Road, after all.

- A friend who lives somewhere else once said to me, “Sabon Gari is very corrupt.”

- Beer and prostitution are prohibited in Kano. In 2015, Kano’s religious police, Hisbah, destroyed 326,151 bottles of beer. They had been seized upon entrance to the state. Beer parlours are only found in Sabon Gari.

TO BE IN a city is to be lost in the midst of inanimate things, to be swallowed up by brick giants and bright lights, by the magnificent works of man towering under God’s blue sky. Sabon Gari can be translated loosely as The New Place or The New City or The New Town. The friends who spend the evening trying to sing in key have all gone away, scattered to the east by ambition and longing. When they come home, for that is what Kano is, they must embrace their city whose roads remain the same death-traps but whose sky is as beautiful as any.

***

You can download and read ENTER NAIJA: THE BOOK OF PLACES.

**************

About the Author:

Arinze Ifeakandu was born in Kano and studied Literature in the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where he was editor of The Muse No.44. He is a 2013 alumnus of the Farafina Creative Writing Workshop. His short stories have appeared in a Farafina Trust anthology and in A Public Space magazine where he was an Emerging Writer Fellow in 2015. He was shortlisted for the 2015 BN Poetry Award.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions