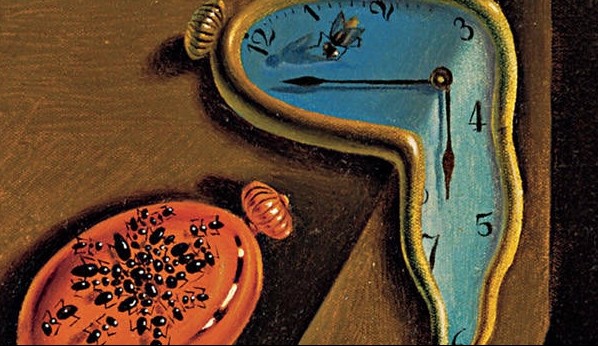

I have a false copy of Salvado Dali’s 1931 masterpiece, “The Persistence of Memory.” It is hanging somewhere not too conspicuous in my house.

The work is an oil painting of melting clocks in a seemingly scorched background—lifeless, save for a few ants eating off the remains of the clocks.

The cryptic nature of the painting prompted my hiding the portrait. How could I explain to friends something I barely understood?

I often talk about the lives and paintings of very famous painters like Picasso, Van Gogh, Frida, Dali, Remambrandt and a few others. Van Gogh is by far my favorite. But somehow Dali’s “Persistence Of Memory” edges out all other works including the elegant disney-scaped “Starry Night” and the unapologetically overrated “Mona Lisa.”

Interestingly, while Dali’s oil painting of melting clocks is my number one brush art of all time, Dali himself wouldn’t make my top ten even in a parallel universe. He was so inconsistent that “The Persistence Of Memory” could have been a fluke.

But it should be remembered that my preference for “The Persistence of Memory”—over other accomplished works by men like Remambrandt, Picasso and Van Gogh—is a purely philosophical bias, a romantic preference somewhat, not strictly artistic.

From an early age I have contemplated time to heretic depths. I have wondered about the beginning of time, the way the world, as we know it, was formed—as we were told. The beginning of God, how He came to be, if he had family or if He came to be when a giant cosmic light got charged by the greatest ever lightening, one that could rip through continents, even planets. The cluster of energy could have been so great that God came out of the biggest smolder, human shaped but with the energy of the world in Him. How else could John and his mortal self have seen Him?

Our world, our time began when God reconfigured a rather shabbily arranged world into its most basic format—night and day, land and sea.

Whenever I pored into Dali’s work, I sought for a new understanding of time, space and fate.

But I have since realized, sadly, that it isn’t possible to contemplate both the beginning of time and the end of time without striking heretical chords, for we live in a society where pondering about time beyond contemporary existence is heresy.

For the end of time speculates the end of Gods existence, the end of all forces of energy, of intelligent life and of the world becoming the hollow landscape described in the Book of Genesis—an eerily dark scape from blasted dream-lands submerged, country-size volumes of water floating, the sun bloated out, drowned.

Analyzing time in our simple existence of now is also not as comprehensible as I would like or as Dali would like. To understand time is to first understand life and death, space and fate.

Staring into Dali’s art this morning, I understand that time is the ultimate force of existence. Fate, space and energy are merely messengers. Time is the compartmentalization of years, the classification of events, the bars separating phases of existence. And for time not to sink into its own hollowness, the sisters of fate, silver-gray and mischievous, must eternally weave out stunning dramas on our world.

Humans have risen against fate in successful rebellions. But for time, no effort has been as daring—not even speculative modules of time machines—as Salvador Dali’s “Persistence Of Memory.”

************

Post Image 1: by Metal Chris via Flickr

Post Image 2: by Mike Steele via Flickr

About the Author:

Julius Bokoru is an essayist, poet, political commentator. He is the author of the (critically) acclaimed memoir: The Angel That Was Always There.

Julius Bokoru is an essayist, poet, political commentator. He is the author of the (critically) acclaimed memoir: The Angel That Was Always There.

Hannah October 05, 2015 17:09

Pretty academic theme with streams of philosophy. It is weird trying to ponder time, something we work with, can't do without, try to beat, try to save, whose passing we mourn, and so on. But thinking too deeply on time itself, beyond what we take for granted, makes my head hurt! "...the bars separating phases of existence". This made me think about the premise upon which time travel rests, that it's a simultaneous existence, how one's twenty-year-old self co-exists with your thirty-year-old self. Of course, I don't know if time travel is believed to exist outside of Hollywood sci-fi, entertaining as it is. Well done, Julius.