Nne my love,

Before the sun sets today, you will be my wife. It’s a day we both looked forward to, the talks of which always brightened your face and made your eyes glitter. I always planned it to be a big occasion. It is. My kinsmen have come colorfully dressed, led by drummers from the famous Ijele troop of my village. Remember the npkokiti dancers we both watched perform at your friend Nkechi’s igba nkwu, those female dancers that had their waists decked in girdles of red beads? I have brought them today to perform at ours too. Yes, I kept my promise. The day I made you the promise, you jumped on me in excitement, almost sending both of us to the ground in pleasant disbelief. Memories of that hug, the feel of your arms around my neck, the softness of your bosom against my chest, spray sweet fragrances on my mind, deodorizing the pain I feel as I write this note. My heart wonders, will you ever hug me that same way, again.

We’ve brought everything custom requires us to bring. You remember how we always joked about bride’s families insisting on a long list of items as though they were selling off their daughter? Well, your family is not any different. The list looked like I was to feed an entire village. But I got everything they requested and more. You are worth nothing less. The tubers of yam, all twenty-one of them are so large each had to be lifted by two people. The palm wine is fresh, we bought up the early morning supply from the best tappers in my village just as they were descending from the palm tree. The list said I should bring three rolls of George wrapper. We came with four. The crates of beer are in excess; my people said it is better the guests stagger home drunk, that way they will talk about today for many moons to come. We didn’t forget the malt drink for the umuada, your kinswomen. Instead of two measures of salt as requested, we came with a bag. My Father, a snuff addict himself made sure the snuff we brought was of the best quality. I am certain your people will continue to bless our marriage each time they sniff it long after today. The mkpi has horns big enough to be used for drinking palm wine. Many people who saw it actually thought we had bought a cow instead of a He-goat. We didn’t forget kolanuts; we will be breaking so many of them today in prayer to the gods.

I sit in the midst of my kinsmen under the large trampoline tent. All about me are red caps and damask head gears. The women are all chatty, all colourful like they always are on such occasions. The men are discussing in hushed tones, their heads bent, their walking sticks lying out in front of them. Seated beside me is Emeka my friend, you remember him right? He’s been very supportive through this period, like a third arm, helping me with the running around. There is highlife music blaring from speakers set all around the compound. Emeka is gently tapping the red earth with his leg and swaying softly in rhythm to the music. Earlier, he had whispered that the music was original Osita Osadebe, not the soulless version some artists in Alaba were dubbing into DVDs and hawking in traffic. I nodded repeatedly in agreement but my thoughts were far away. The beats of the music, the pronounced bass guitar, the subdued ogene, had flicked on a switch in my memory.

Highlife music also rented the air the day we first met at the nmechi aro festival of our Town’s Union in Lagos. You were helping the women serve food at that end of year celebration, your face covered with sweat, your hands stained with red oil from mixing abacha. Yet, your beauty was pleasantly jarring, the way your hair glided down your shoulders like a waterfall, the way you made the air still when you spoke. Your appearance was inviting enough already but it was the way you dutifully went about serving the abacaha, picking up the used plates and responding to everyone who needed a second helping or a tooth pick, with a smile, that lighted the flames in my heart. I felt pulled to you, to the freshness of your smile, to the refinement in your demeanor, to the air of sweetness that hung around you like a halo. I kept staring like a teenager, lurking around and hoping you would notice me. I worried I would stutter when I finally got a chance to speak to you.

You would later tell me, during your first visit to my house a month later, that even before I finally walked up to you that nmechi aro day, you had noticed me, my eyes like beams following you all over, my stare like darts poking holes all over your body, my serious mien hardly masking my desires. What you might not have noticed on that day was that I had made quick enquiries about you and about your family. It was good to learn you were an undergraduate at the University of Lagos. Emeka had laughed a deep throaty laughter that left me worried that he would choke, when I mentioned that I was interested in you. “Bia, odika nmaya ana egbu gi” He said suspecting I must have had too much alcohol, that I was beginning to hallucinate. You were off my limits he thought. Educated university girls did not take interest in illiterates like me he said, certain that you would shoo me away like a goat even before I finished introducing myself.

To be sincere, Emeka’s words made me feel inferior that day, even inadequate. I am not an illiterate, really. I completed my secondary school before going to Onitsha to learn a trade because I didn’t pass Mathematics. But Emeka was right. Educated ladies often laughed away the advances of my kind, calling us omata, except we had lots of money and drove an SUV. I had neither, but I was far too intoxicated by you to stop. I had gone beyond the threshold of reasoning. I decided to at least try.

Nne, it was magical, almost mystical, the love we came to share. Its instantaneity was marveling, how that day we had stayed on at the nmechi aro festival venue long after others had left, chatting like old friends, you, laughing at my weak jokes. When I first approached you and greeted you, you did not respond to me in English like most university girls would have. You responded in Igbo so rich in the accent of our dialect that I even felt slightly intimidated. That is one of the things I love about you Nne, the way you spoke your Igbo with such self-assuredness, such musical fluency that made it sound like something else, like something celestial.

Sitting here today, listening to the Master of Ceremony make an opening remark interrupted at intervals by claps, I remember with nostalgia, the moments we shared. I remember how you would come around to the shop and help me get my books right. You were a third year accounting student, and you taught me how to make my business better by calculating my profit and loss. I remember you introducing me to the cinema, how we would occupy a corner of the hall giggling and eating our popcorn a little too noisily while the movie lasted attracting the envy and disgust of other movie watchers. Sometimes we were too involved with ourselves that we missed much of the movie, trooping out with the throng at the end oblivious of what the movie had been about. I remember taking you to the club on Friday nights and how initially you complained about the smell of Hennessy but grew to love its taste so much I had to start keeping a bottle at home. I remember the sex, the urgency of it, the loudness of our moans, the pleasant embarrassment I felt each time my next door neighbor complained to me, of how our sensual noise making kept him awake, horny.

Nne, I am still wondering what went wrong on that fateful night, still stuck in a cesspool of confusion about how we lost it all. Did we overdo it? Was it the drinks you had at the bar, or was I too hard with my thrusts? Personally, I suspect the drinks. Maybe it didn’t sit well with your heart, that mixture of energy drink and red wine. I wasn’t quite comfortable with it, but I did not stop you. I encouraged you instead, teasing that you needed the combination of energy and intoxication to survive what I had in store for you that night. You laughed as you gulped glass fills down. I still hear it in my head today, your laughter which produces a sound that seems to emanate from your lungs rather than your throat. You know you turn me on when you laugh like that, your bosom rising and falling rhythmically, your eyes narrowing, your open mouth exposing your tongue snaking around suggestively. That night was no different. Like two horny teenagers we had rushed up our drinks and jumped into a cab to my house eager to quench our desires.

How special it had been that night Nne, me and you occupying the deepest recesses of ourselves, giving, taking, and conquering. What adventures we led ourselves into that night. What new grounds we discovered. What new heights we reached. It was like we knew it would be our last. Thinking of it, there couldn’t have been a truer expression of the love we shared, one which we reiterated to each other over and over in passionate whispers with promises that we will hold it forever. Alas, forever came too soon when like a scene from a horror movie, you suddenly went still and collapsed in a heap, on top of me.

You know initially, I thought you were just catching your breath. I also needed to catch mine so I laid there taking in deep gasps of air with my mouth, the ceiling above spinning in circles. I could feel the beating of my heart reach a crescendo like an army was marking time across the left of my chest. I teased you for wanting to kill me that night. But you did not respond with banters of your own as you usually would have. You did not move. It was weird that you could have slept off so suddenly with me still inside you. I tapped you gently on your back. I even made some thrusts. But you wouldn’t stir. That was when the boot soles began a quick march in my chest. That was when somebody threw a blanket over the sun.

So I am here today my love, a groom and a widower. I have come to marry you like we planned. I have also come to mourn you. I know this might sound strange to you, this contradiction playing out today. You are not alone. I also feel like it is all insanity. But that is the blow fate has dealt us, the judgment tradition has pronounced on us. They said it is an abomination, for a girl to die in bed with a man she was not married to. Your family rose up in arms demanding my head. The things I have endured these last few weeks…the shame, the condemnation, the ridicule. Do you know it was even reported in the newspapers gossip columns? People spoke of it with disgust, as though we were the only unmarried couple that had sex, like we were two demons caught in a city of saints. Some even said I must have used you for money ritual, that I had offered you as sacrifice so that my business will begin to boom. Can you imagine that Nne? Me use you for rituals? The police quickly dug into their charge book and found a name for it; murder. They locked me up in Kirikiri with criminals for a whole week. It was like a nightmare, the manhandling, the mosquitoes, the hunger. But I endured it all for you, for us, and for all the promises we hold and share.

Today I have come to perform the ceremony of our cleansing, to secure my acquittal from the court of tradition. It is the settlement my people and yours reached, the only condition under which the police released me and dropped charges. They said I would have to come and marry you the way tradition prescribes. For your spirit to find rest they said, the ties that bind us must be sealed. I must then also perform your funeral and mourn you like a husband mourns a wife. The two events both families agreed were to hold at once, on the same day. So we have come today with music and wine, with gifts and food to marry you and also a casket to take you home to my place where a freshly dug grave is waiting to house your remains.

After today, I will be acquitted by tradition but will I ever feel cleansed? Will I ever forgive myself for your loss, for my role, for that moment when I could do nothing but scream your name? Will I ever forget the image of you sprawled on my bed, your eyes agape as if in a trance? O, Nne there is a lot that gnaw at my heart when I lie down at night to sleep, a lot that I need to find answers to. Answers I desperately hope will help me make sense of this cruel fate life has dealt me. As I sit here, observing as some elders from your family and mine go back and forth doing the traditional haggling over the bride price and sharing jokes in idioms as if this is a normal marriage ceremony, I feel the clouds gather in my eyes and I wish for them to rain down oceans deep enough to drown the guilt I feel.

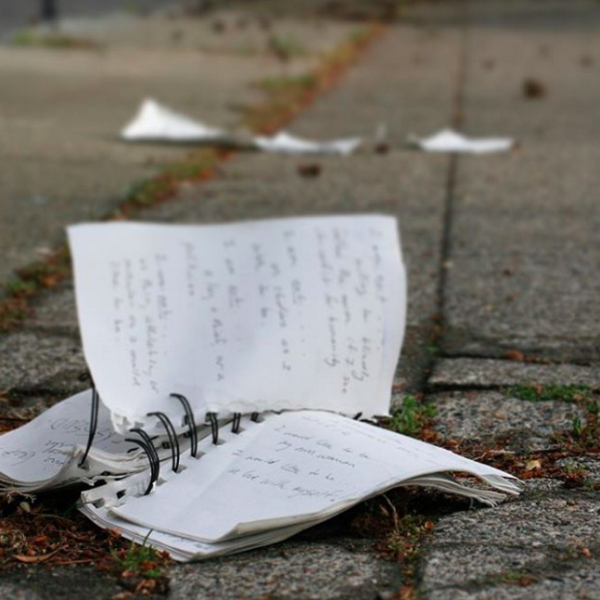

But I am not allowed to cry until later in the evening during the other ceremony. Even then, it must be brief. I have been told that I must be cheerful and merry, because it is my wedding day and men do not cry on their wedding day. So I tear out the blank sheet from the last page of the printed program to write you this note. Hoping you understand. Hoping also that you keep that which we shared alive, until we meet again.

Your husband,

Obi.

About the Author:

Sylva Nze Ifedigbo, fiction writer and op-ed columnist lives in Lagos Nigeria. His works of fiction and socio-political commentaries have appeared in many publications both online and in print, including Prick of the Spindle, African Writer, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, Saraba, Kalahari Review, Story Time, NEXT, and Pixelhose. His novella, Whispering Aloud, was published in 2007 by Spectrum Books. His collection of short stories, The Funeral Did Not End, was published in Nigeria by DADA Books in 2012. You can see more of his work and purchase his books on his website.

Sylva Nze Ifedigbo, fiction writer and op-ed columnist lives in Lagos Nigeria. His works of fiction and socio-political commentaries have appeared in many publications both online and in print, including Prick of the Spindle, African Writer, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, Saraba, Kalahari Review, Story Time, NEXT, and Pixelhose. His novella, Whispering Aloud, was published in 2007 by Spectrum Books. His collection of short stories, The Funeral Did Not End, was published in Nigeria by DADA Books in 2012. You can see more of his work and purchase his books on his website.

My Stories | Nzesylva's Corner April 23, 2019 17:46

[…] Will you hug me again in Brittle Paper | March 2016 […]